This is the third part in a series of 12 monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration in June 2017. It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that are published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom. © Len Lazarick 2016

Links to all 12 parts of this series are at the bottom of this essay.

By Len Lazarick

Tony Tringali is a living fossil, a historical remnant of ancient Columbia. His barbershop in the Wilde Village Center is not just antique; it qualifies for a plaque as a historic landmark of the Founding Father’s plans.

Tony is the last merchant standing from those that opened their doors 49 years ago for the first Columbia residents. Before the mall, before Route 175, before the eight other village centers opened, there was Tony. [Unfortunately, Tony died March 20, 2017, six months after this article was first published.]

Through thick and thin, he’s been there. In recent years, it’s been mighty thin as the Giant grocery that opened with him was first expanded and then torn down. Regular customers like me would have to figure out how to get to the shop hemmed in by construction fencing, mud and broken sidewalks.

“We’re still getting people back,” said Tony one hot August afternoon. Some might never return.

“Basically I’ve had a good following for many years,” said Tony. The walls of his shop are covered with hundreds of photos of youngsters getting their locks shorn. As we talk, he pulls out a fresh photo of three generations, grandfather and son standing with a young grandson sitting in Tony’s chair as his father did, memorialized in a decades-old snapshot that hangs on the wall.

“I’ve done these people for generations,” he said. “I’ll probably do them for as long as I’m around.” (UPDATE: Tony died March 20, 2017.)

Home-Grown

As a teenager, Tony’s family moved from Baltimore to Beaverbrook, a development that preceded Columbia. He went to Howard High School. “I used to play in these fields” that became Columbia, he said.

Gone are those other first Wilde Lake shops: a butcher, a cheese shop, a Rouse-backed community bank, an independent drugstore, a dry cleaners. Other stores, like a Hallmark card shop and a sweater store, moved to the mall when it opened four years later. There have been too many restaurants to name, and, of course, the anchor, the Giant.

“It was the best Giant they had when it first opened,” Tony said.

Tony represented the original village center ideal. Its merchants were the commercial center of community life, with other essentials clustered around it — a library, a community hall, a religious facility, a swim center, a high school and a middle school.

Tony was familiar with the village center concept from his early years in Baltimore’s Edmondson Village. Already part owner of a barbershop in his early twenties, he wrote a letter to the Rouse Co. It approved his plan, and with a long-gone partner named Richard, he opened Anthony Richard, a barbershop with a beauty salon next door.

“I would do it again,” Tony said. “It worked for me.”

Columbia’s earliest village hubs didn’t work out as planned. Lifestyles changed, markets shifted, and every sector of retailing changed drastically to adapt.

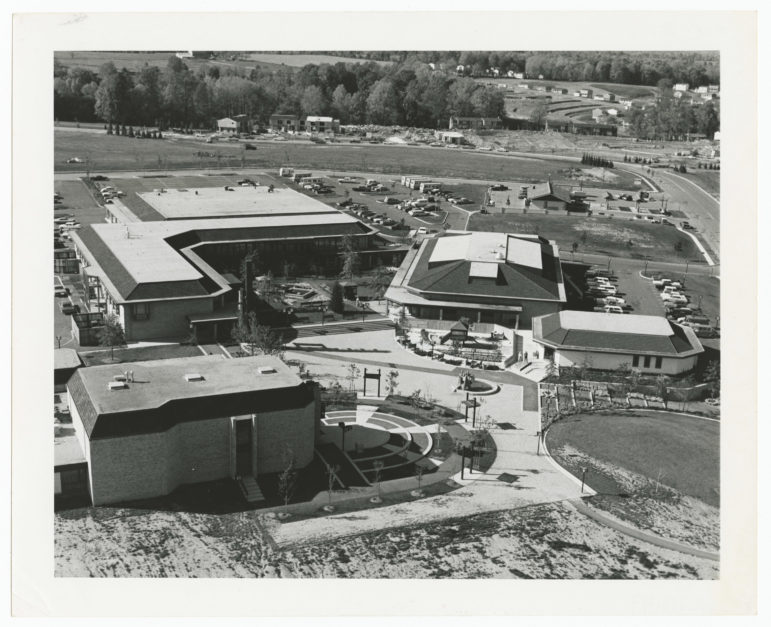

The original Wilde Lake Village Center under construction in 1967. Photo Courtesy of Columbia Archives.

A Hub of Services and Community Life

Shopping and retailing are the heart of Columbia and its villages. Without a grocery store, bank, drugstore and other services, a collection of homes is just a suburb, like the smattering of developments that existed before Columbia. In Wilde Lake, the new residents were pre-serviced — facilities were opened before there was the population to support them, as were the original neighborhood centers and pools. It was one of the attractions of early Columbia.

Wilde Lake, the first village, was a living showcase of the Columbia plan trotted out for the national press.

The mall too was central to the plan. As envisioned by master developer Jim Rouse, the mall was to be Columbia’s Main Street. According to Josh Olsen’s biography, Rouse, whose company pioneered the indoor shopping mall nationwide, rejected the recommendation that the mall be located near the newly built Interstate 95. He wanted it at the center of town.

For Columbia’s first decade or so, the mall served as the center of social and commercial life, as portrayed in the new novel Wilde Lake by Laura Lippman, who attended the original Wilde Lake High in the 1970s when it was still round and experimental. Lippman captures the social dynamics of growing up in Columbia and the role the mall played as hangout for teens and adults as well.

Shifting Lifestyles

Changes in the way Columbians lived were summed up in 1997 by Wayne Christman, general manager of Columbia Management, the Rouse Co. subsidiary that oversaw all the company’s commercial real estate in town.

“Thirty years ago, Rouse created a city founded on a village concept … to give the people a central core location … along with open space and athletic facilities to help them focus on their community,” Christman told The Business Monthly. “Now, with two-income families the norm, few people have time to use the village center like they used to.”

There also were problems with layout and design. The first four village centers — Wilde Lake, Harpers Choice, Oakland Mills and Long Reach — were all inner focused, with stores facing each other, and their anchor groceries were too small.

“What used to be a state-of-the-art village center grocery store consisted of 20,000–25,000 square feet,” Christman said. “But grocery stores evolve, driven by market needs and desires. Now a store [has to be] 55,000 square feet and have a deli, a pharmacy, a florist, fish counter, salad bar and other things that our stores don’t even have.”

Later centers all had larger groceries. Dorsey’s Search Village Center, opened in 1989, and River Hill Village Center, opened in 1997, are designed more as strip shopping centers with easy in and out. The last center, River Hill, is at the fringe of its village at a major intersection, far from similar competition.

Over the years, the first four centers have struggled. Harper’s Choice was redeveloped with a new Safeway and a more open, strip-like configuration; the Giant in Wilde Lake was expanded. But problems continue to plague Oakland Mills and Long Reach on Columbia’s east side.

Residents of these older Columbia villages felt abandoned by the Rouse Co. as new competition opened with larger stores not far away. Rouse itself was undermining these smaller centers by its own developments, beginning with Dobbin Center in 1982. The strip center was anchored by a Hechinger home improvement store and a Bradlees.

For its first 15 years, any Columbia resident with a major home improvement project had to go elsewhere to shop. The opening of Hechinger at Dobbin Center was a boon to the locals, even as it spelled the doom of the hardware store along Lynx Lane in Wilde Lake.

The same pattern would hold true for the next two decades. Large retailers with chains of stores established themselves on the land that rings Columbia’s residential areas east of Route 29 and competed with the village centers for business. These new stores were also a response to a changing Howard County market, as development occurred to the north and south. Columbia was no longer the only center of residential growth in Howard County, though it continued to have the greatest concentration of land for stores and businesses.

Ten years after Dobbin Center opened, Rouse developed Snowden Square with land it had acquired from General Electric.

Big Boxes Arrive

A new trend in retailing, the big box store, was giving fits to all those regional shopping malls Rouse Co. had spearheaded across America. For developer Rouse, if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.

Hechinger fled Dobbin Center for a box at the end of Snowden Square, 40% bigger to offer a wider range of merchandise. Anchoring the other end of the square was B.J.’s Wholesale Club, the membership warehouse store competing with many smaller Columbia merchants including the chain grocers.

“There’s an unfilled demand for this type of shopping in Columbia,” said a Rouse Co. official justifying the selling of the land. Columbia residents “have to leave the area” to shop at these types of stores, he said. And of course, the new big boxes were highly visible along a major highway just a couple of miles from I-95 where the Mall in Columbia wasn’t built.

In 1997, Columbia Crossing got underway north of Route 175 across from Dobbin Center with more big boxes — Target, Dick’s Sporting Goods, a massive Borders book store, and more chain restaurants on the outer rim.

In 2002, Rouse abandoned the village centers altogether, selling the eight it owned to Kimco Realty Corp., of Hyde Park, N.Y. The community-centered retailing of the town’s early years faded in the face of market pressures and changing lifestyles.

(A residual effect of Rouse’s precarious finances in the 1970s was the development of the Owen Brown Village Center by Giant Food’s realty division 1978. Later, Giant found it needed to expand its own store and create something more like a strip center.)

The Mall

But Rouse still had the mall, Columbia’s Main Street. Unlike the village centers, the Mall in Columbia was never just for Columbians. It never could have survived; it was a regional shopping center, and when it opened in 1971, it was one of the best. Jim Rouse wrote to one of his executives that the new mall was “better than anything else the company has recently developed.”

Even young architect Frank Gehry told Rouse he was “overwhelmed.” “It is the most beautiful covered mall I have ever seen,” he gushed.

Initially many of the merchants were local, like the Bun Penny deli, one of the last survivors that finally shuttered its windows in early 2008. In its first decades, the mall was also a central place for Columbia celebrations, like the Ball in the Mall.

But over the years, the Columbia mall came to look much like regional shopping centers across America, many developed and managed by the Rouse Co. across the street.

Local merchants in the mall were replaced by chains, often with the same product lines. Locally owned eateries were replaced with a food court, chain-run.

The mall was evolving from its earliest years. The original Hoschild-Kohn anchor department store was acquired in 1975 by the Hecht. Co., which years later became Macy’s. Woodward & Lothrop, a regional department store, was replaced by the national J.C. Penney.

In 2004, The Rouse Co. was sold to General Growth Properties, an operator of regional shopping malls, which were the major part of Rouse’s assets.

The company that had nurtured the village centers and controlled all of the land use was out of the picture forever. There was no longer a benign developer with its own headquarters in the middle of town guiding the process. For the first 40 years, Rouse had decided where the stores and offices would be built, where the neighborhood and community centers would go, where the schools and athletic facilities would be located, even where the worship spaces could be built.

Even when Columbians rose up in opposition to its development plans, the key decision makers were close at hand.

But, just four years into the new century, that benign developer was gone. Most of the residential land had been sold as lots, now owned by thousands of homeowners and hundreds of landlords. The business parks, once overseen by a developer with a stake in building community, were now in the hands of many. As the economy waxed and waned, the properties were bought and sold, some turning over multiple times.

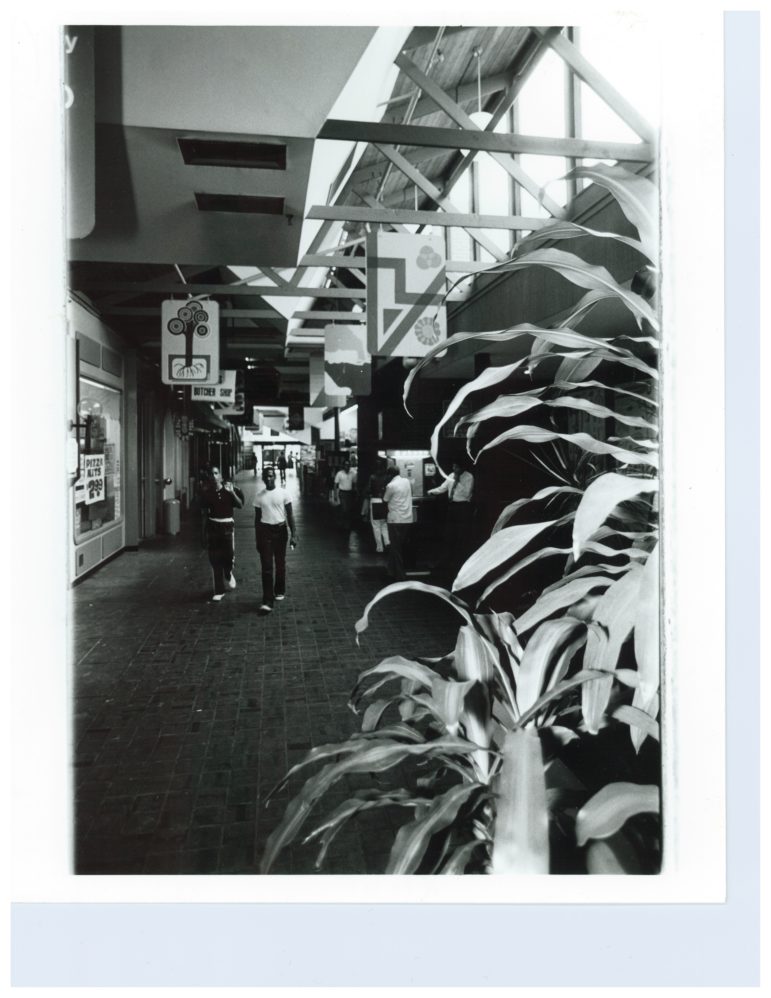

The interior courtyard of the original Oakland Mills Village Center. Photo courtesy of Columbia Archives.

Problems at the Older Centers

The problems that plagued the old centers did not go away when Rouse left the scene; they just came under new management. While all five of the older village centers had their problems, few were in worse shape than Oakland Mills and Long Reach.

From the day it opened, Oakland Mills was doomed to be a hidden marketplace. The center was built in the wrong place.

Nearby residents want to believe otherwise, but the center is difficult to find, and sits on no major thoroughfare. It probably should have been built on Route 175. (The same could be said for Long Reach.)

Compounding a fundamental error in real estate development — a bad location — Rouse first built a mini-enclosed mall, with a grocery that was far too small. Pantry Pride gave way to a Giant that eventually closed. The old center was shut down and redeveloped into the strip center we know today, anchored by Metro Food Market. That eventually failed as well, leaving the space vacant for more than two years.

Finally, Food Lion agreed to take the space. Residents cheered.

Jeff Metzger, publisher of Food World, a supermarket trade journal based in Columbia, was dubious.

“I would say opening a grocery store [there] no matter who operates it is a risk,” Metzger told the Baltimore Sun in 2003. “I just think that’s a poor location. It has nothing to do with the quality of the retailer. … The demographics [there] aren’t particularly strong. [The area is] really land-locked [and] there’s no access to any major road.”

The wonder is that the Food Lion is still open. A shopper with agoraphobia could find some peace there, with empty aisles all to himself and checkout with no lines to speak of. The Food Lion will close Friday Sept. 16, to reopen as a Weis Markets store Sept. 23, the fifth food chain to make a go of Oakland Mills.

A large Exxon station next to the center closed in 1999. Its 1.7 acres covered in aging asphalt have sat vacant now for 17 years. Multiple proposals have fallen by the wayside, including County Executive Ken Ulman’s promise for the county to purchase part of a planned condominium office building that never got off the ground.

Many Chances to Eat

The restaurant scene in Oakland Mills is almost an exaggerated parody of the vicious turnover typical in the trade. A frequently quoted statistic from the National Restaurant Association is that 60,000 restaurants open each year, while 50,000 close, for various reasons.

An early cover story I did for the Columbia Flier showed what a brutal and complicated business this can be seven days a week, from purchasing the ingredients, to preparing them and delivering them to table. Getting it right every day is hard to do, which is why chains and the formulas they maintain have come to dominate.

Because restaurant spots come with kitchens and bars, they tend to remain restaurants. So it is in Oakland Mills. Let us count the names: Long’s Vineyard, The Crackpot, Phase Three, Barnums, Skipjack’s, Channing’s Crab House, Last Chance (which wasn’t) and now the Second Chance Saloon. Other longtime survivors that have seen the anchors go and come are Vennari’s Pizza and Lucky’s China Inn.

While Oakland Mills may have persistent troubles, it at least has traffic and surviving merchants with food to sell. The poor Long Reach Village Center is effectively a zombie, walking dead to all appearances. Opened in 1974, the Safeway doubled in size in 1998 but shuttered in 2011; the Asian food market that replaced it stopped paying rent and was evicted. There has been no anchor for three years. Half the storefronts are empty, the eateries are long gone, and its most active merchants appear to be a liquor store and a Subway.

Kimco had unloaded the center in 2004 to another out-of-state firm. After the anchor store went empty, the situation was so bad that the county purchased the center to revitalize. Consultants have been hired, work groups and community meetings have been held, but those plans are now up in the air.

Long Reach residents have long since found other places to shop. There is a Giant in what was once a movie complex across Rt. 108, the nearby Target or Wal-Mart along Dobbin Road, BJ’s and now the massive Wegmans on the site of what was once a warehouse and offices (and the soundstage for “The Wire”). Wegmans, with its shops within a store for baked goods, meat, cheese, fish and prepared foods, is a megastore much larger than the other chain groceries it aggressively competes with.

Remembering the Restaurants

The various Facebook pages dedicated to remembering Columbia or discussing its future are evidence of how important an eatery or a watering hole can be. A community may chat in the grocery stores, but it builds relationships over food and drink.

Longtime Columbia residents have their favorites. There have been few neighborhood bars and eateries as beloved as JK’s Pub on Lynx Lane in Wilde Lake, a knock-off of a British pub that opened in 1978 with a dark wood bar, antique mirrors and down-home cooking. I would often walk across the fields of Wilde Lake Middle School from the Columbia Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway for a lunch of specially bought liverwurst and onion on rye with a glass of rosé. It was the kind of place where you saw people you knew — lawyers, politicos, and for Friday happy hour, groups of teachers from nearby schools . Everybody didn’t know your name, but many people did, all presided over by John and Claire Lea.

JK, a former university speech professor always ready to declaim, sold the operation in late 1994, complaining of 70–80-hour work weeks, the familiar lament of many restaurateurs.

“Sometimes it seemed like I was working around the clock,” Lea told The Business Monthly. “This is a younger person’s job — it’s very demanding, There’s always something you should be doing.”

And then of course there’s Clyde’s, the grand old man of Columbia’s eateries and a glaring exception to the turnover in the restaurant trade. I covered its crowded opening party 41 years ago, with its layout much as it is today. My story made note of the $2.50 hamburger and $1.40 glass of wine, which seemed a bit pricey to me in 1975, but is pretty laughable today. My publisher reminded me that I was a business reporter, not a restaurant critic. For decades, it was the place for the power lunch and the let’s-talk-business-over-drinks happy hour.

The Banks

Banking is one of those essential services that any thriving community should have, and was a key component of any village center.

It’s been more than 40 years since I opened my wife’s and my joint account with Columbia Bank & Trust, a company founded here with Rouse backing. I’ve never moved that account, but with mergers and acquisitions, we’ve had four banks since then. In succession, the bank was named Equitable, Maryland National Bank, NationsBank, and now for many years, Bank of America. We’ve gone from deposits in a small town bank to one of the behemoths too big to fail.

This reflects the enormous consolidation the industry has gone through, said Mary Ann Scully, president of Howard Bank, which services my MarylandReporter.com account but is temporarily without a branch in a Columbia ZIP code. Howard Bank is pretty much what’s left of community banking here, as most other banks, including another home-grown Columbia Bank, where my business has a credit card, is owned by out-of-state holding companies.

“Everybody wants to be a community bank,” said Scully, but “it’s probably not been executed very well. Poor execution hurts the not-for-profits and small businesses.” The not-for-profits “get a bigger share of the dollars at community banks.”

Howard Bank once had a branch in Hickory Ridge, where I opened my account, but “we’re going to vote with our feet by having a branch in Little Patuxent Square,” the Costello Construction high-rise directly across from a mall parking garage.

“It is important that Columbia reach the Jim Rouse vision” of an urban environment to remain competitive for businesses and talent, Scully said. “If not, we lose our young people and lose our businesses.

“Having a more urban environment is very important,” which is why Howard Bank has supported the downtown Columbia revitalization plans. “Some banks think it’s political” to support the plans, Scully said, “but we believe that banks should be community leaders.”

Of course, who actually goes into a bank these days, as people did in Columbia’s early days, to deposit paychecks and get cash? Most transactions are now handled by ATMs and online, and even grocery stores dispense cash.

The new David’s Natural Market with the apartments in Wilde Lake under construction. Photo by Len Lazarick

David’s Natural Market

Revitalization has its costs. In Wilde Lake, barber Tony Tringali is not the only surviving victim of its struggles as Kimco demolished the old Giant and a third of the village green.

David London was 27 when he took over his parents’ decade-old natural food store in 1986, turning Nature’s Cupboard of Love into David’s Natural Food Market. David, a graduate of Wilde Lake High, grew up working in the natural foods business.

His store at the end of Lynx Lane expanded six or seven times over the years, going from 1,000 square feet to 12,000 square feet, taking over space once occupied by Duron and JK’s Pub. “We got to grow with the community.”

The village center “was a great concept when they first developed it,” David said, so that residents could “do their shopping in their own neighborhood.”

But people changed, and they wanted to do their shopping “quickly,” gravitating to “more strip-type centers.”

When Kimco proposed redeveloping Wilde Lake with 250 new, five-story apartments and without a traditional grocery, local residents were up in arms. They wanted a grocery the way Rouse had planned, even though Kimco insisted no chain would locate there.

But David bought the concept, and planned a fine new market for his organic foods and herbal products that would anchor the center, along with a shiny bright CVS drugstore.

At first he was told Lynx Lane would be closed for two weeks for the construction, but that dragged out into nine months. Customers had trouble figuring out how to find the old store. The new market was to have opened in March 2014, with brand new equipment, but it actually wouldn’t greet new customers till eight months later.

“It’s just killing us,” David said. “We lost 30% of our business, and we haven’t gotten it back yet.”

While the months dragged on, the new Whole Foods opened in the former Rouse Co. headquarters less than two miles away. But David said he doesn’t see it as a competitor.

“We try to offer more personalized service,” David said. “All my employees have been there for a long time,” like Barbara Wright, the chef manager of the health foods cafe who had worked the kitchen at JK’s Pub.

“We’re local; we’re part of the community,” David said.

But in retrospect, “it was a lot more money than I thought,” he said. “It would have been easier to open a new store than to move it.”

He said it may take as long as 10 years to recoup the investment. “Thank goodness I had two others stores,” one in Gambrills and a second in Forest Hill, Harford County.

“I think it will be OK,” especially as renters occupy the apartments next door, David said. (A similar redevelopment process has been proposed for the Hickory Ridge Village Center that opened in 1992, with Kimco proposing the addition of an apartment block. The current Giant would stay, but the retail that faces it on a courtyard would be relocated around the parking area.)

Barber Tony Tringali thinks David’s Natural Market will appeal to the new residents. “They don’t have to cross a major street,” Tony said. And the residents of the new apartments downtown will find parking easy.

“Every place you look out here you see a crane,” said Tony. “I don’t see why we can’t get our fair share” of business from the new residents.

Next month in Columbia at 50: Media

Len Lazarick ([email protected]) has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics, and a political columnist for The Business Monthly. This article is copyright © 2016 by Len Lazarick, email: [email protected]

Part 1: How the ‘garden for growing people’ got planted and grew

This is the first of a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. In this first installment, Len Lazarick looks at how a new town with ambitions to be a real city “not just a better suburb” came to be on 14,000 acres of Howard County farmland with lofty goals that faced some hard realities.

PART 2: Working in Columbia: Its Downtown and Business Parks Went Up and Down With The Economy

Part 2 focuses on the businesses of Columbia as an essential part of the plan.

Part 4: MEDIA in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest

Part 4 examines the role of media in creating the Columbia community, primarily newspapers, and in particular, the Columbia Flier.

Part 5 POLITICS: The Shifting Weight of Columbia Power

This month looks at the shifting dynamics of political power in Howard County because of the presence of Columbia and its largely Democratic voters.

Part 6 EDUCATION: Schools Were Crucial Then and Now

Part 6 examines the planning and transformation of a small, rural, recently desegregated school system with middling rankings to one of the best school systems in the country. Howard County now has 76 schools with 54,000 children and 4,100 teachers, and they face the challenges of diversity, particularly in its urban core of Columbia.

Part 7: HEALTH CARE: Planning for a healthy community — an innovative HMO, a hospital fight and the quest for wellness

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help. The opening of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics in 1973, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

Part 8: RELIGION: Interfaith centers sought to bring congregations together

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia. While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all.

Part 9 ENVIRONMENT: Respecting the Land While Building a City

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys. The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were? Because they were not going to stay that way for long as suburban development spread from Baltimore and Washington along the new interstate highways.

Part 10: ARTS at the Heart of the New Town

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first structures built before Columbia even had its first residents. Now it is being redeveloped and is at the center of the Merriweather District that is the core of Columbia’s new downtown. But Merriweather is only part of the arts scene in the planned community.

Part 11: Recreation and the Role of the Columbia Association

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Association. As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them. As Columbia looks to the future, CA not only wants to keep the pools and athletic facilities open, but to keep Jim Rouse’s vision alive.

Part 12 Conclusion: A 50-year-old town faces its future

Veteran journalist and longtime resident Len Lazarick wraps up by looking back over the past 50 years and looking forward to Columbia’s future. All 12 chapters have now been published as a 200-page book.

Recent Comments