This is the 11th part in a series of 12 monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration in June 2017. © Len Lazarick 2017

It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that, was published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom.© Len Lazarick 2017

Links to all the essays are at the bottom of this story. They have been compiled into a 200-page book available here.

By Len Lazarick

Rachel Lazarick, 4, gets ready to swim at a meet in summer 1988. Photo by Len Lazarick

Three-and-a-half-year-old Rachel Lazarick jumped into the pool at the mini-meet in the summer of 1987. Despite swallowing some water, she managed to swim the 25 yards to the other end. The Owen Brown swim team coach had suggested that the young swimmer, who was taking lessons, could manage the distance. Her 7-year-old sister was already on the Barracuda team.

For the next decade or so, our family’s Saturday mornings in June and July were consumed by meets of the Columbia Neighborhood Swim League. Wife Maureen Kelley would serve as clerk of the course, handing the kids those fateful cards listing their events, as well as the team manager. I would be first a timer and then, after some training, a stroke-and-turn judge. It takes about 20 to 30 adult volunteers to run your average swim meet.

As our daughters became year-round competitive swimmers in the Columbia Clippers — one of the largest USA Swimming teams in the region — there was taxiing them to daily practices, including, as they grew older, the dreaded early morning ones. There were the regional meets across Maryland and even into Virginia and Pennsylvania.

Thousands of parents and their children in Columbia have followed a similar path over the years, a tiny fraction of the population, but more than in most places due to the almost unheard-of number of pools in Columbia.

My two daughters became not just competitive swimmers but lifeguards, pool managers and coaches. Rachel went on to captain the Salisbury University swim team, and Sarai has continued to work in Columbia Association (CA) aquatics for many years, as a lifeguard trainer and auditor among other roles. It all started at the Dasher Green pool, a 10-minute walk from each of our two homes over the last 39 years.

In the Swim

Columbia has 23 outdoor pools and four indoor pools. A professional study in 2001 found Columbia has about four times as many public pools as any city of its size — though it also found that Columbians patronize their neighborhood pools about five times as much as elsewhere. By comparison, Washington, D.C., six times the size of Columbia, has 36 public pools.

Each of the 10 villages, except for Town Center, an anomaly in most things, has at least one CA pool, and most of the neighborhoods of the first seven villages have a pool.

A pool open in Maryland’s hot, humid summers was one of the key elements of the neighborhood concept by Columbia’s planners, the essential building block of Columbia villages. As originally conceived, the neighborhood was a walkable community with an elementary school, a convenience store, a neighborhood center and a pool at its core.

As we found in chapter 6 on education, as the school board balanced county-wide interests with the school-age population, not every village would get a high school, and not every neighborhood would get an elementary school. Just a handful of the convenience stores survive, but supported by Columbia Association and its annual charge, none of the 23 pools that opened over the years have ever been permanently closed, even the one or two that have as many visitors as staff on some summer days.

No, the pools are the “center of life within Columbia,” one resident told the CA board, reacting to the consultant’s report recommending that one or two pools be put to a different use. What a blow to the community it would be if they closed one of those pools, a CA board member would say.

Private Governance

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Park and Recreation Association. (It is not “Parks” in official documents, although that was common usage.) As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them.

As discussed in chapter 5 on politics, the Columbia Association, as CPRA quickly came to be known, was a compromise over the other forms of governance that were considered. (The name officially changed in 1991.)

Remember the context. Howard County was still largely rural with a few suburban developments as Columbia planning began in 1964. The county had few urban services or public amenities. It did not have its own Recreation and Parks Department until 1969, begun that year with three people.

Jim Rouse and his firm were committed to a “garden for growing people” and building a city, not just a better suburb. They wanted to provide as many urban amenities as possible, with no added financial burden on the county government.

All the governmental forms the planners looked at — a municipality, a town, a special taxing district — couldn’t accomplish what Rouse wanted on the swiss cheese of landholdings that the company had acquired. Cities, towns and municipalities cover all the land within specific boundaries, and they can’t go into debt without the current revenues to back it up.

Rouse wanted to provide recreation and community facilities to Columbians, and he and his planning team wanted some of them to be in place as residents were moving in, leveraging the financing based on the future growth. This was called preservicing.

The developer also wanted to do this without putting an immediate burden on the residents by raising the cost of land to the builders, who would simply jack up housing prices. The Rouse Co. subsidiary, Howard Research and Development (HRD), also didn’t want to increase the company’s own already sizable debt accumulated from buying the land, planning and building the streets, landscaping and utilities.

The Rouse Co. also wanted to maintain control of CA during the most intense development period, something it also could not do with a governmental unit run by officials chosen by the citizens. At the start, the board of directors of CA was made up entirely of Rouse Co. executives, including Jim Rouse himself. According to the charter, for every 4,000 occupied housing units, a resident representative would be added. Zeke Orlinsky, publisher of the Columbia Flier who lived then in The Cove on Wilde Lake, was the first.

Perpetual Covenants

The solution to those competing goals was the Columbia Park and Recreation Association. Current CA President Milton Matthews pointed out that the Columbia Association is actually older than the official start date of Columbia, having been established in 1965, a year and a half before the new town welcomed its first residents.

As the Rouse Co. began selling land to builders or putting up apartments, stores and offices itself, it established perpetual covenants on the land. Every time land and buildings change hands in Columbia, those covenants are attached in perpetuity. With the covenants comes the lien, essentially a property tax on all residential and commercial land based on its assessment. The covenants also establish permanent architectural controls over what buildings should look like and how they can be changed.

As with most Rouse Co. planning, the role of CA, the preservicing of facilities and the architectural controls had multiple purposes. They made the community more attractive and more conducive to personal and community growth. But they also increased the value of the land that was to be sold, then and in the future. CA was a vehicle to implement social purposes, but it was also a marketing tool and a boost to the bottom line.

Jim Rouse’s 1968 correspondence files show that the company paid close attention to how to explain CA to residents, going through several finely honed drafts before the brochure explaining CA was printed.

“Open space was woven throughout the city, enhancing the beauty, utility and value of homes and apartments,” it said. There was “landscaping and architectural controls far beyond those normally provided.”

“Architectural control assures construction of buildings throughout the city not in rigid conformity but in good taste and in harmony …. [They] guarantee that the standards of design and taste that you see in Columbia today can be maintained forever.”

Mounting Debt

From 1965 to 1971, essentially as an arm of the developer, CA would construct the two lakes, Wilde and Kittamaqundi; the lakefront plaza; the Wilde Lake Swim Center and tennis club; the Athletic Club in Harper’s Choice; the Ice Rink in Oakland Mills; Slayton House and community centers in those villages; the neighborhood pools and buildings; open space and pathways; and Symphony Woods. CA also operated a transit system, as it would for another 20 years, and provided day care and after-school care.

With only a few thousand residents and a smattering of commercial properties, its construction and operating debt continued to mount — all to be paid off in the distant future from the lien on the properties.

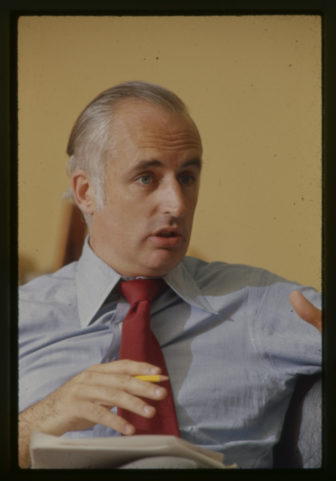

CA President Pat Kennedy, circa 1980s. Photo by James Ferry from the Columbia Archives.

It was not until 1972 that CA got its first full-time president, Padraic (Pat) Kennedy, who would guide the association as it evolved over the next 26 years. Kennedy is tall, bright, charming, imaginative, a brilliant conversationalist, a respected manager and about as adept a politician as one could imagine juggling the competing interests of developer and residents in the odd governance structure that Rouse had created.

He recalled that while he was recruited by Jim Rouse himself, and would live right next door to Columbia’s founder for decades, he would actually work for a board of directors that over the years had 12 different chairpersons and 77 elected village representatives, and deal with six successive Howard County executives, along with dozens of county, state and federal representatives.

He saw the best of times — and the worst of times as well.

“Columbia’s success was not assured in those early days. Still there was a great sense of optimism,” Kennedy wrote in an essay. “Mud was everywhere. Bulldozers were busily preparing roads and carving out sites for future homes. Signs heralded ‘The Next America’ and everyone knew they were part of something special.”

Kennedy remembers his first years as “an explosion of creativity.” More facilities were built — a visual arts center, Lake Elkhorn, a petting zoo, more child care and youth employment services. Dance floors, mirrors and ballet barres were installed in community centers.

Recession

Then in 1974, the Arab oil embargo and a deep national recession slowed Columbia development to a crawl, pushing HRD to the edge of bankruptcy. “CA almost went under,” Kennedy recalled in an interview, especially as Gov. Marvin Mandel changed the property tax assessment system, reducing CA’s lien income.

CA, like the Rouse Co., was forced to cut staff and operating costs and refinance its mounting debt. “The fundamental objective of the period was getting CA through the national economic crisis,” said Kennedy. “They were difficult days for everyone.”

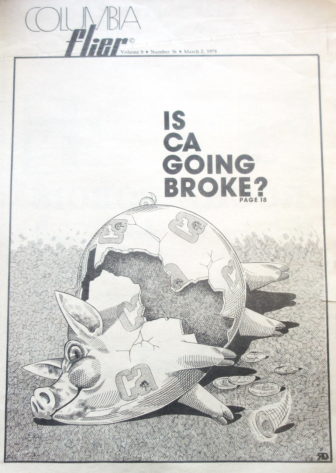

I joined the Columbia Flier as associate editor in 1975, and while CA was not really part of my beat, some residents pushed for state political solutions to the problems of CA and its mounting debt.

As some residents realized, there were drawbacks to the way CA was structured — some still are, like the inflexibility of a governing structure based on land covenants. The lack of resident control over what was still an arm of the developer rubbed people the wrong way.

(Only after Kennedy arrived were the meetings of the CA board and its governing executive committee opened to the press and public. When this was first proposed in 1970, Jim Rouse in a handwritten internal memo described the prospect as “very, very dangerous.” The openness and transparency of CA under Maryland’s homeowner association laws is still a matter of dispute.)

As a private entity, not a governmental unit, CA also paid market interest rates on its long-term loans and bonds, at one point as high as 8–10%. Municipal bonds or even the revenue bonds from a special taxing district could be sold at much lower rates. And the lien, which operated as a property tax, was not deductible for state and federal income tax purposes — although depending on the mortgage lender, it sometimes was lumped in as a tax on escrow accounts and deducted anyway.

After months of study and debate in 1977, there was a proposal for a special taxing district that would replace CA, but the proposal died. There was some question whether a district that basically supported amenities would qualify for a tax break.

After months of study and debate in 1977, there was a proposal for a special taxing district that would replace CA, but the proposal died. There was some question whether a district that basically supported amenities would qualify for a tax break.

In March 1978, I wrote a long cover story for the Columbia Flier, “Is CA going broke?” It explained the whole concept of preservicing, and talked with several bond holders and financial analysts before coming to the conclusion: “If you believe Columbia will grow and prosper, the answer is NO,” CA was not going broke.

HRD and CA survived in a leaner fashion. And in 1982, as Columbia development picked up and its population grew to 57,000, control of CA passed entirely to the elected representatives of the villages, where it remains today.

Organized Sports

Swimming held a special place for CA, which owned most of the aquatics facilities in Howard County except for some private swim clubs. But most of the other team sports, inside Columbia and out, were played on school grounds or in school gyms.

The star of the show is the Soccer Association of Columbia/Howard County (SAC), which began in 1971 with a small loan from the Columbia Association. Soccer was a late arrival to the sports scene in the United States, but it seemed to have a special appeal to Columbians and their children. It can be played by a wide array of athletes of different sizes and abilities and of both sexes with a minimum amount of equipment.

On Facebook, many people who grew up in Columbia remember with nostalgia the early days of Columbia soccer where neighborhood teams in different colored jerseys competed against each other.

“In the early days, Columbia Maryland was the soccer capital of America,” Laddie Wilson reminisced on Facebook last year. “I would not be too far wrong if I said high school soccer was as big here as high school football in Texas and basketball in New York City.”

“Darrell Gee and a few other locally grown soccer players starred on the U.S. national soccer team. Columbia even had a professional soccer team!”

A 1986 interviewer asked Jim Rouse what Columbia might look like in 20 years. Rouse admitted he didn’t much believe in such forecasting, but guessed that Columbia might have a soccer stadium, since “soccer will become by then a very major sport.” That did not come to pass, nor did his vision for an opera house and symphony hall.

By the 1990s, there were 6,000 kids playing soccer in Columbia and Howard County. The nonprofit SAC eventually supported a small full-time staff and built its own dedicated soccer fields off Centennial Lane, in addition to the scores of sites at schools and parks.

On Memorial Day weekend, Columbia does become sort of a soccer capital, at least for the mid-Atlantic. “Here, arguably, is the heartland of U.S. soccer,” a Sports Illustrated writer proclaimed after visiting the tournament in 1989.

There are 665 teams signed up for SAC’s 42nd annual Columbia Invitational Soccer Tournament in May 2017. The tourney requires so many fields that teams will be playing not only throughout Howard County, but also in Olney, Owings Mills and the BWI area. Hotels are booked up far and wide.

Sportstown USA

Soccer is only one of the sports for which volunteers and participants have stepped up to develop clubs; there’s also baseball, basketball and running. And they’re not just for kids.

In 2004, Sports Illustrated dubbed Howard County a Sportstown USA, meaning it was Maryland’s best community for amateur sports. At the time, the county’s director of recreation and parks, Gary Arthur, estimated that 62,000 countians of all ages took part in 74 competitive sports run by 30 different groups, mostly led by volunteers.

The 34th annual Columbia Triathlon takes place in May. It started in 1983 with 90 people swimming, biking and running and now attracts upwards of 2,500 competitors. The first triathlon ended at the Columbia Swim Center in Wilde Lake, but now the race, one of the oldest triathlons in the U.S., begins with an almost mile-long swim in the county-owned Centennial Lake.

The Howard County Striders running club has been around for 40 years and has about 1,800 members. It hosts seven large races a year, mostly in and around Columbia on Sunday mornings, and many smaller events. On April 10, 2017, 626 runners finished the Clyde’s 10K, among them Greg Fitchit, vice president of the Howard Hughes Corp., the company that is redeveloping downtown Columbia. Dave Tripp, former director of investor relations for the Rouse Co., was president of the group during its early years, assisted by his wife Judy Tripp, who edited the Business Monthly for 14 years.

The Columbia Neighborhood Swim League has had its ups and downs as the villages age and the number of children decline. In 2003, 16 years after my daughters began swimming in meets at the ages of 7 and 3, they were coaching competing teams: Sarai for the Thunderhill Lightning and Rachel for the Owen Brown Barracudas. At the suggestion of their father, who can recognize a good story, the Columbia Flier did a nice write-up about the pair headlined: “Sibling rivalry: Two sisters ready teams for duel in the pool.”

The Columbia Neighborhood Swim League has had its ups and downs as the villages age and the number of children decline. In 2003, 16 years after my daughters began swimming in meets at the ages of 7 and 3, they were coaching competing teams: Sarai for the Thunderhill Lightning and Rachel for the Owen Brown Barracudas. At the suggestion of their father, who can recognize a good story, the Columbia Flier did a nice write-up about the pair headlined: “Sibling rivalry: Two sisters ready teams for duel in the pool.”

Sarai told the reporter: “I’m coaching a team that’s swimming against a team that I coached for four years, who I swam on since I was 7, and again, I’m coaching against my sister, so it’s a big deal.”

“I’ve always wanted to do what she did,” Rachel said. “It was never about being better. It was like, ‘She’s swimming, so I’m swimming; she’s playing soccer, so I’m playing soccer; she’s having fun, so I want to have fun.”

Thunderhill won. Both daughters are now public school teachers. They began learning teaching skills as teenage coaches.

Pressure on the County

As Columbia’s population grew, though more slowly than projected, the county’s population outside Columbia was growing as well. It almost doubled in the 1970s to nearly 120,000 people — half living in Columbia — and would grow by another 70,000 people in the 1980s, increasing the demand for public parks and recreation both outside and inside Columbia. The example set by the Columbia Association led Howard Countians living outside the town to ask: “What about us?”

The Howard County Recreation & Parks Department that started 48 years ago with three employees had a full- and part-time staff of 1,271 in 2016. It maintains 9,159 acres of public lands, more than 50 parks, and offers more than 7,000 recreation programs.

In some cases, the county and CA work cooperatively, such as with the 4.6-mile Patuxent Branch trail that begins below CA’s Lake Elkhorn dam and winds down to Savage. Under contract, CA also maintains many of the county-owned median strips in roadways.

An aerial views of new ballfields at Blandair Park in East Columbia. Route 175 is on the right. Photo by Howard County Government.

Another big addition to the county’s portfolio is coming online this year with the completion of phase 2 at Blandair Park, 20 years after its owner died without a will. Elizabeth Smith had refused to sell the 300 acres that straddle Route 175 in the middle of East Columbia to the Rouse Co. or other developers, and she died without signing a will she had prepared. Phase 2 will add two more lighted synthetic-turf ballfields to the three already built at the park. A new entrance road was built off Route 175.

Few residents will know or much care about the distinction between land and facilities owned by Columbia Association, Howard County government or their school system, as long as they’re available when the residents want to use them.

Staying at the Top

The leadership at CA sees itself in partnership with the county government and residents in keeping up the attributes that led Money magazine to name Columbia the best small city to live in in America last September. Several times in the past decade the town had been in the top 10 of this annual ranking by editors of a publication based in New York City.

“The Columbia Association is in the quality-of-life business,” said Milton Matthews, president of CA since 2014.

CA President Milton Matthews. CA photo

“I’ve always been interested in Columbia” since his days in grad school for urban planning, said Matthews, who held a similar post in Reston, Va., the Robert E. Simon new town in Fairfax County. “I like being here at this time during the redevelopment phase as Columbia prepares itself for the next 50 years.”

Matthews said he emphasizes to CA executives that “what got you to the top is not going to leave you at the top.” This means upgrading and improving the community’s recreation and community facilities, a process that began some 30 years ago under Pat Kennedy.

“We’re very much aware that the competition is picking up for us,” said Matthews. That’s among the reasons CA developed the upscale Haven on the Lake spa on the ground floor of the former Rouse Co. headquarters that’s now home to Whole Foods.

Staying at the top also means maintaining the 3,600 acres of open space, three lakes, 40 ponds and 94 miles of pathways that are a key attraction for Columbia.

But Matthews and CA Board Chair Andy Stack, who’s been involved in the governance of the village of Owen Brown and CA for most of the 40 years he’s lived here, agree that CA also has the larger role of maintaining Jim Rouse’s vision and social goals for a racially and economically diverse community.

“The social concepts are just as valuable” as the physical structure, Matthews said.

“CA is the only organization that can keep the vision alive, and keep Columbia as a planned community for the future,” said Stack.

Maintaining the Vision

Much as the original physical planning for Columbia was designed to reinforce social goals, so CA’s role in maintaining the public amenities and physical appearances goes hand in hand with promoting Rouse’s goals.

CA has now paid off the heavy debt it accumulated in its first decades, and can focus on repairing, replacing and rehabilitating its existing facilities.

CA Board Chair Andy Stack. CA photo

That also means enforcing the architectural covenants as the homes, apartments, stores, offices and commercial buildings age. The annual charge on the value of this real estate also provides almost half of CA’s $77 million budget. “If you don’t have redevelopment, you’re dying,” Stack said. “You want people to take care of their houses.”

And take care of their commercial buildings as well. While the village boards and CA enforce the architectural covenants on residential property, after the demise of the Rouse Co., the covenants passed on that role for the commercial property to the Howard Hughes Corp.

There’s “a great deal of interest” in taking over that covenant enforcement for Columbia’s business parks, Stack said. But CA would have to add staff and procedures to do that, as well as figure out a way to pay for it.

As owner of Symphony Woods and the Kittamaqundi lakefront, CA also has intense interest in what happens to the downtown development that will increase population and assessment. “I do think Rouse envisioned higher density” there, Stack said.

“There’s a role CA has to play according to the principles Jim Rouse laid down,” Stack said. “There’s a large focus from CA to do that.”

Next month: The final chapter

Part 1: How the ‘garden for growing people’ got planted and grew

In this first installment, Len Lazarick looks at how a new town with ambitions to be a real city “not just a better suburb” came to be on 14,000 acres of Howard County farmland with lofty goals that faced some hard realities.

Part 2: Working in Columbia: Its Downtown and Business Parks Went Up and Down With The Economy

Part 2 focuses on the businesses of Columbia as an essential part of the plan.

Part 3: Shopping and Retailing at the Heart of the Columbia Plan

Part 3 examines the central role of shopping and retailing for the development of the Columbia plan. With changes in both lifestyles and retailing — and a couple of poor locations — the village centers did not always work out as planned.

Part 4: Media in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest

Part 4 examines the role of media in creating the community, primarily newspapers, and in particular, the Columbia Flier.

Part 5: POLITICS: The Shifting Weight of Columbia Power

This is the fifth part in a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. This month looks at the shifting dynamics of political power in Howard County because of the presence of Columbia and its largely Democratic voters.

Part 6 EDUCATION: Schools Were Crucial Then and Now

Part 6 examines the planning and transformation of a small, rural, recently desegregated school system with middling rankings to one of the best school systems in the country. Howard County now has 76 schools with 54,000 children and 4,100 teachers, and they face the challenges of diversity, particularly in its urban core of Columbia.

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help. The opening of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics in 1973, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

Part 8: RELIGION: Interfaith centers sought to bring congregations together

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia. While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all.

Part 9 ENVIRONMENT: Respecting the Land While Building a City

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys. The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were? Because they were not going to stay that way for long as suburban development spread from Baltimore and Washington along the new interstate highways.

Part 10: ARTS at the Heart of the New Town

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first structures built before Columbia even had its first residents. Now it is being redeveloped and is at the center of the Merriweather District that is the core of Columbia’s new downtown. But Merriweather is only part of the arts scene in the planned community.

Part 11: Recreation and the Role of the Columbia Association

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Association. As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them. As Columbia looks to the future, CA not only wants to keep the pools and athletic facilities open, but to keep Jim Rouse’s vision alive.

Part 12 Conclusion: A 50-year-old town faces its future

Veteran journalist and longtime resident Len Lazarick wraps up by looking back over the past 50 years and looking forward to Columbia’s future. All 12 chapters have now been published as a 200-page book.

Recent Comments