This is the 12th and final part in a series of monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration this month.

It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that is being published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom.© Len Lazarick 2017

Links to earlier essays are at the bottom of this story. It has now been published as a 200-page book that can be purchased here.

© Len Lazarick 2017

By Len Lazarick

No one had ever lived in apartment #301 at 8812 Tamar Drive in Long Reach when we moved in in June 1973. Called Bentana, it was brand-new, with two bedrooms and parquet floors. A balcony overlooked an empty field across the street where bobwhites could be heard. Rent was $200 a month, but the first two months were free, a signing bonus for the newest apartment complex in Columbia’s fourth village.

Columbia was 6 years old, and Maureen and I were making a fresh start in new jobs in a new place very different from the urban commercial strip we had left in Boston’s Brighton neighborhood.

We were in the South, Maureen said, and I laughed. This is Maryland. “Yes, south of the Mason-Dixon line,” she pointed out. Her Rhode Island accent would mark her as a foreigner to some of the patients she would see as a visiting nurse. A native of Philadelphia, I had spent time in Baltimore, D.C. and Ocean City. Maryland was hardly the South to me, but I discovered Maureen was more right than I was once I learned more about Howard County.

We were hardly “pioneers,” in Columbia lingo, those people who had moved in amid the mud and bulldozers of the new town’s first 12 months. But things were still very new. The Long Reach Village Center a short walk away would not open for a year. We would wind our way over Oakland Mills Road to the little Pantry Pride supermarket in the long-gone enclosed village center, since Route 175 had not yet been built. The Mall in Columbia and the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center had just opened two years before.

The housing, the shops, the schools were fresh and modern. So were the people, like us, mostly younger couples starting families — the term baby boomer had just been coined — and even older couples in their forties with kids in high school looking for a different kind of suburb. Most, like us, were from out of state, and there was a 1960s vibe about everything in this community that was to be environmentally sensitive and open to all races, faiths and incomes living next to each other.

The new town was not about old ideas, old people, old houses, old stores, old offices, but in its 50th year that is much of what it has become.

In the original economic model, Columbia was to be completed in 1980. In earlier installments, we have seen how a recession and an oil embargo delayed the time frame. These events were accompanied by high inflation and then price controls that kept our rent steady for two years.

These factors were among the many outside forces that were not foreseen or factored into the original Columbia plans.

An aerial view of downtown Columbia shot May 2, 2017. Brent Meyers Aerial Photography for Len Lazarick. Below, a model of downtown Columbia shown to Howard County residents in 1964. Courtesy Columbia Archives.

Women’s Liberation

Feminism would have to be at the top of the list of things that had not been foreseen. The planners of Columbia were all white men with traditional families. The planning work group of professors and consultants in various fields included just one woman. This was 1963, at the very beginning of the women’s liberation movement in the United States, ignited by the publishing of Betty Friedan’s book, “The Feminine Mystique.”

An early marketing brochure for Columbia shows a large picture of a family: a “creative” wife in a dress, three kids, a dog, and a suited husband with a briefcase. The expectation was that dad would go off to work and mom would stay at home, even if she were college educated. There would be outlets for these educated “creative” wives outside of the home — pools and tennis courts, arts and crafts, and child care facilities.

And of course the stay-at-home moms would gather around the cluster mailboxes after the mail was dropped off. Really? I have heard this sexist old wives’ tale — or if you prefer, “urban myth” — repeated in print and in person, as recently as last month. Maybe it was so at the beginning. I rarely saw it.

Allegedly a community-building amenity, group mailboxes were actually, as best as we can determine, an experiment by the post office to reduce the cost of delivery. By 1978, what had become the U.S. Postal Service would demand that all new suburban developments across the nation have curbside or group mailboxes; no more door-to-door delivery. A 1995 USPS study found that cluster mailboxes cut the cost of delivery per home by more than half. Now such centralized delivery is found in tens of thousands of developments across the country. My sister has one in Mesa, Ariz.

The planners’ vision of domestic tranquility did not match what was going on in the culture as a whole. Columbia had to adapt to women working outside the home, the two-income household and the demand for all-day child care. Still excluded from the leadership of major business institutions — even in the forward-thinking Rouse Co. there were “men and girls” — women developed their own institutions in the arts, the media and nonprofit organizations.

“If it wasn’t here, you had to start it,” recalled pioneer Helen Ruther. Many of these women are now among the hundred honored in the 20-year-old Howard County Women’s Hall of Fame.

The changing role of women did not come easily. Power of any kind, after all, is usually not given away but must be taken. There were many battles fought and won or lost, or a truce declared. One small but significant battle was Columbia resident Mary Stuart’s fight in 1972 to keep her own name on her voter registration and her driver’s license. She won the lawsuit on appeal, but married couples with separate names are still an oddity for some people and databases, as Maureen Kelley and Leonard Lazarick can attest.

The most visible success of the women’s movement, as it once was called, was in Howard County politics. Women first made up a majority of the County Council in 1982. One of its members, Liz Bobo, became Maryland’s first female county executive in 1986. Five women currently are among 12 state legislators, and the elected school board has been all-female for several years, except for the student member.

Few young women call themselves feminists these days, yet most have benefited from the expansion of opportunities for women brought about by the movement. On the other hand, many of the homemaking burdens of the two-income family still fall on women.

The asphalt river, Route 29 looking south May 2, 2017.

Two-lane Route 29 looking south in the 1960s before Columbia. Courtesy Columbia Archives

The River and the Wall

A key to Rouse’s plan for developing a community was maintaining control of what was placed where to build up a sense of community, land values and the bottom line. But there are so many forces outside the control of the developer — the economy, interest rates, the role of women, divorce, county politics and even the State Highway Administration.

There are two small rivers that run through Columbia, with many streams flowing into them. The big river that divides Columbia now has a wall to buttress that division. Route 29 is that asphalt river.

When Columbia began, it was a two-lane highway, with several at-grade crossings with traffic lights. In the 1970s, it became four lanes. In 1992, the last traffic light was replaced with Broken Land Parkway overpasses connecting east and west. Now there are six lanes, often choked with rush hour traffic due to the building of high sound barrier walls along its east side. The cars come mostly from outside Columbia.

Most of the important institutions in Columbia are west of the Route 29 river. The iconic images of Columbia are taken looking west over Lake Kittamaqundi, the way the first model for the new town shown to Howard County residents was photographed. From “The People Tree” and the fountain on the lakefront plaza; to Columbia’s first office buildings and exhibit center; to Symphony Woods and Merriweather; to the first village center, the community college and the hospital, all are west of Route 29. Rouse executives and many of its first community leaders lived west of the Route 29 river, as well, and now there’s a wall.

In that original model, there is a bridge across the highway, seeming to connect to the Oakland Mills Village Center, the most isolated of the struggling centers. Instead, Route 175 and Broken Land Parkway cross the river. The pedestrian bridge from Oakland Mills is slated to be improved, but it only connects to downtown by foot or by bike, which is not how most residents travel back and forth.

Seldom do we see the view looking east depicted. It is most assuredly green until you hit Dobbin Road and Snowden River Parkway. On the edges of this greenery that make up the villages of Oakland Mills, Long Reach and Owen Brown are the big box stores and the bulk of Columbia’s employment centers. The BJ’s, Wegmans, Wal-Mart, Apple Ford and other car care outlets, along with the business parks, are arguably as important institutions to many residents as most anything in Town Center.

Then again, Rouse’s notion was that people would be more conscious of living in neighborhoods, connected at their core by a village center with all the essential services — except the gas stations in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills are long-gone. People can’t go much of anywhere without a car, and if they don’t leave Columbia, they pay some of the highest gas prices in the Baltimore region.

Commuting

A core Rouse ideal was that people of all ages, backgrounds and incomes would live and work in Columbia. That ideal couldn’t survive the patterns of work and housing in post-industrial Maryland — or the success of the new town itself, even in its early years.

On Columbia’s sixth birthday in June 1973, the month Maureen Kelley and I moved in, editor Jean Moon wrote the Columbia Flier cover story bemoaning the lack of the promised diversity.

“Where are our ‘blue collar’ workers, those 2,700 men and women who work at General Electric, located in the town with the ‘sound economic base.’ Where are the 6,500 construction workers who are building this city?” Moon asked.

“They are not here,” she went on. “Not in Columbia where more than one out of four residents has completed post-graduate work. They are not among the doctors, dentists, lawyers, engineers, architects, planners and government employees who comprise the majority of our working population.”

This is the city that Jim Rouse said would provide “houses and apartments at rents and prices to match the income of all who work here, from company janitor to company executive,” she wrote.

Moon critiqued the rapid rise in housing values that allowed the early settlers to make a killing on their low-priced townhomes and move on to something bigger and better — further putting housing prices out of the reach of middle incomes.

“We are so successful that we are really a failure,” Moon said. Not much has changed in 44 years, except the need for two incomes to afford to live here.

The notion that most of these professionals would somehow work in Columbia was never true. Today, at least two-thirds if not more of employed Columbia residents have commutes of greater than 15 minutes. This means they travel to work somewhere outside the boundaries of Columbia in a region with some of the worst commutes in the country. As in the past, many people work at the National Security Agency in Fort Meade or its contractors, or at Social Security in Woodlawn, or in Baltimore, or in the Washington suburbs and even the capital itself. Rush hour traffic jams near NSA are routine.

Tens of thousands more employees flow into Columbia’s business parks from elsewhere in the region. Many of these non-Columbia residents will not tread too far off the major roads to venture into the Columbia villages, lest they get lost in the loop streets and maze of cul-de-sacs with funny names.

Jim Rouse himself commuted to Columbia from Baltimore until he bought a home in 1974. Columbia pioneers planning their 50th birthday reunion laugh recalling the debate about whether the non-resident Rouse should be invited to their fifth birthday get-together. Columbia now has its own suburbs in Clarksville and Ellicott City. Maple Lawn just south of Columbia could be mistaken for another Columbia village.

County officials, the Columbia Association (CA), the Howard Hughes Corp. and many others still struggle with finding ways to provide affordable housing for even middle income teachers, cops and residents without the federal housing subsidies that fostered Columbia’s housing mix in its early years. Attracted to the new town’s cheapest housing, many minorities sacrifice much to buy and rent in Columbia for its better schools, or use their Section 8 vouchers.

The housing bubble of the early 2000s followed by the housing bust in the Great Recession did not help the cause to make living here affordable.

Retail Hurricane

The turmoil in retailing has been going on for decades. Columbia’s village centers were once dominated by small merchants and supermarkets, some of them locally owned. (Giant, once dominant in the region, is now part of a CORRECTION Dutch corporation.) All of them are threatened by discount grocers and warehouse stores, like Wal-Mart and Costco. The original Columbia supermarkets were not built large enough for all the special services the modern chains needed to add.

The biggest changes are in the regional shopping malls that Rouse pioneered, that helped to kill the downtown department stores that once flourished in big cities till their customers moved to the suburbs.

Urban historian Howard Gillette wrote that Columbia has been “described, accurately enough, as a city built around a shopping mall.” Rouse rejected the advice of his own planners to locate the mall near I-95. He envisioned it central to the town, as Columbia’s Main Street. In its first decade, it was full of local merchants and community activities.

On Facebook pages, Columbians and folks who grew up here wax nostalgic about hanging out at the mall or getting their first job there. But malls have been constantly evolving. Three of the four anchor department stores at the Mall in Columbia — Sears, J.C. Penney and Macy’s — are struggling to survive the Internet wave and competition of the big box stores the Rouse Co. would build here. Two of the mall’s original anchors are gone, and Macy’s is the third occupant in that same building. Sears recently closed its top floor.

The Rouse Co. had for decades gained most of its revenue from its national network of shopping malls, a source of some resentment in the company where Columbia got much of the spotlight. Rouse executives probably picked an excellent time in 2004 to sell the business, given the trends in retailing since.

Once at the center of community life, the Mall in Columbia is now a hub of commercialism surrounded by a sea of parking lots. The latest trend in urban planning is for more mixed-use development — mixing apartments, shops and civic uses together as seen in the revamped Wilde Lake Village Center, the Metropolitan apartment complexes near the mall and the future plans for the Merriweather District.

The mall, which Jim Rouse considered one of his company’s best, was one of the key selling points to the women who already lived in Howard County when Rouse first pitched his idea for a new city. Given its location and its affluent market, it seems likely to survive the shuttering of regional malls across the country.

Howard County Executive Ken Ulman talks to reporters with Gov. Martin O’Malley and police officials at his side as the mall reopened after the fatal shooting. Governor’s Office photo by Jay Baker.

Crime

In January 2014, the mall bounced back quickly from its worst calamity, the fatal shooting of three people, including the suicide of the gunman. What the incident revealed, among other things, was how well the Howard County police and its young, Columbia-born executive Ken Ulman responded to a crisis that was blasted across the national news. It gave Columbia more, but more negative, coverage than it had received in decades. It also disclosed that the county police had quietly practiced shelter-in-place drills with mall personnel that would have saved lives in a worse shooting incident.

For many Columbia residents, crime has no place in any narrative of their time here. “One of the advantages of Columbia is that you feel safe,” said Ethel Hill, a longtime resident, activist and former Columbia Association board member who moved here from West Philadelphia in 1969.

As the news editor of the Flier and Howard County Times for four years in the 1980s, crime was one of the beats I supervised — murder, rape, assault, robbery, embezzlement, drug busts, child abuse, all occurred at one time or another. My late mother once told me she didn’t read newspapers because they contained so much bad news. Sorry, Mom, but that’s what we do.

I once had to tell a new Flier reporter that there had been a change in plans, and she was being switched to the cops beat. She broke down in tears. At a previous job, she had been traumatized by covering a murder that she could smell as she approached the victim’s house.

Columbia indeed is safer than many places, and certainly safer than North Philly where I went to high school or West Baltimore where my wife has seen patients for years. But besides my professional connection supervising cops and courts coverage, crime has hit close to home.

In October 1985, a Washington Post distributor was stabbed to death in the early morning hours outside the High’s convenience store next to the Dasher Green pool where we all spent so much time. We didn’t get our Post that day. Police soon arrested the 19-year-old who had left a note on the body taunting them. He lived in our neighborhood a short walk away.

Less than a year later, there was another murder with much closer personal connections. Aruna Mittal was suffocated in her home, where she had provided day care for my daughters until just a few weeks before. Her husband first claimed it was a robbery gone bad, a report that set the neighborhood on edge. It turned out her husband actually did the crime, as part of an affair with Aruna’s sister who lived with them. When Maureen and 6-year-old Sarai attended the funeral, they didn’t realize they would be seeing their first Hindu cremation.

Our current house was broken into before Christmas the following year. No one was home. The audio system and some Christmas gifts were stolen. I regretted not having installed the bars over the basement window that the thieves had crawled through. The police investigated, and eventually arrested two teens who lived on the next cul de sac. Columbia’s wooded pathways have many uses.

In 2005, my 3-month-old Honda Accord was stolen from our driveway during the night. The owner had stupidly left the valet key in the center console; otherwise, the car thieves might not have been able to drive it off after breaking in. A day or two later, the speeding car, with five people inside, was involved in a high speed police chase up Route 29 and onto Route 40 toward the Patapsco State Park. The occupants eventually bailed out by the park, fleeing into the woods. State Farm wound up paying $12,000 to repair the almost-new car.

From the fingerprints, Howard County police eventually tracked down all five occupants of the car, all Columbians, a couple of them juveniles. As a victim, I got to witness my first juvenile hearing for one of the boys, clad in orange jumpsuit and chains. Nabbing all the males involved was a surprise. A bigger surprise came months later when I got a check from the state as restitution for the items stolen from the car.

Lemonade

I could go on and on about the things in Columbia that went wrong, weren’t planned or didn’t succeed. The bad news my mother avoided.

That was not Jim Rouse’s way, as he reminded us at a lunch on Founder’s Day at the community college on May 9, 2017, organized to discuss the developer and his vision with the Rouse scholars, the college’s honors students. On film, he related the oft-told story of the first meeting of the Work Group in 1963. Round and round the experts at the table went, telling him how and why his city for growing people wouldn’t work and couldn’t work. The same happened the second day, until finally one of the group said, wait a minute, aren’t we talking about fostering love in a community? And the whole tenor of the discussion changed.

“Everybody comes with a vested negative,” Rouse tells the video interviewer. In an earlier video, we had heard Rouse say, “The development business is one of managing crises. … There’s no such thing as an adverse event.” It’s how it is handled that counts, he said.

That’s why, on the wall of his office, Rouse had a framed poster of the now-familiar saying popularized by Dale Carnegie: “When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.” Rouse was forever making lemonade, adding sugar and ice to many situations, and selling it to people who couldn’t believe how quenching it was.

A series of interviews with many of the early settlers by a University of Maryland anthropology class in 2015 found them no less enthusiastic.

“Interviewed residents, regardless of when they first moved in, agreed that Rouse’s original vision and goals remain important for Columbia. Some expressed a concern that the goals have weakened over time due to rapid population growth, increased emphasis in pursuing profit over growing people, and larger changes in society,” their report found.

“Residents cited increasing traffic congestion, the technology revolution, better understandings of the natural environment, rising housing prices, generational turnover, and new incoming populations as areas Columbia will need to address in planning ahead for the future.”

The students found that “many newcomers didn’t know about Rouse’s vision or goals until they were brought up in interview.” While the social goals were more elusive, the dedication to the environment and open space won some over, despite earlier misgivings.

Adam Herson moved to Columbia at the end of 2012 after repeated visits to a friend there.

“I didn’t like just about everything about Columbia,” he said. “You pretty much had to drive everywhere. The fact that you couldn’t find anything. There are no signs.” Over time, Herson became impressed that “pretty much everywhere is nothing but green.”

That respect for the land led to 94 miles of pathways through streambeds and woods that actually establish most of the boundaries of Columbia’s 10 villages and 32 neighborhoods — its basic building blocks.

Harvard urban design professor Ann Forsyth, who has studied Columbia for many years, said this open space planning “took advantage of the strengths of the rural landscape but has made the shape of each neighborhood and village difficult to perceive from the ground, because the edges are literally buried in trees.”

In almost any aerial view of Columbia, even its densest Town Center, the buildings are always poking out of trees. First-time foreign visitors often remark how green it is.

“Open space is probably one of the major successes of Columbia,” environmental author Ned Tillman said. “Many cities and towns did not do a good job of that.”

Forsyth returned to Columbia for Founder’s Day, with a new focus on creating healthy environments from urban design. Her studies have found that the greenery display not far from most any doorstep in Columbia is good for mental health, not just the physical health of walkers, joggers and bikers. “Rouse instincts were pretty good,” Forsyth said.

Cherishing Diversity

It is the socio-economic, racial, ethnic and religious diversity that Columbia’s longer residents most cherish, as does Dr. Terri Hill, who represents west Columbia in the House of Delegates.

Ethel Hill’s daughter moved to the Running Brook neighborhood with her parents in 1969 when she was 10. Her father worked at Social Security in Woodlawn, as many Columbians still do. Her older sister Donna, who would eventually become a judge and deputy attorney general, was among the first students at the new Wilde Lake Middle School and then the Wilde Lake High in Columbia’s first village. Both schools were innovations designed to operate in the round. Both have been replaced, the middle school in 2016 as a solar-powered building. In the round, some students flourished and others languished.

“By the time I got [to high school], we had schedules, but you were still working at your own pace,” said Terri Hill.

Hill, who is African-American, threw herself into Columbia’s opportunities — the winter swim league, dance classes, lifeguarding, using the Call-a-Ride system to get around. She was president of her Wilde Lake High class in her junior and senior years.

She went off to Harvard and then Columbia University for medical school, and Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital for a residency in plastic surgery.

“When you leave Columbia and start dealing with people from other places, you realized how different Columbia is,” said Hill, who returned in 1991. “I still think Columbia is something special.”

Her high school classmates get together for reunions every five years, and “a lot of them live in Columbia. … My closest friends are still in Columbia,” Hill said. Many of them left and came back as she did.

Newcomers to Columbia are different from those early decades. “People come for the amenities and not [for] a community based on a shared ethics and values,” Hill said. Like many of the old-timers, she mourns the long-gone Exhibit Center where new arrivals would learn of Rouse, his goals and housing opportunities.

“I think it’s still striving to be that community with very unique beliefs in socio-economic, ethnic religious mix. I do think it works toward those goals.”

The 50th birthday events a coalition of community organizations is sponsoring seek to remind Columbia residents of what the planned community was supposed to be.

Reminders also take place on Facebook and in blogs and private chats.

A typical comment came from Tricia McDonaugh in 2016: “I just want to take a moment to say how privileged I feel to have grown up in Columbia. My own children are mixed race and we have lived in the south and north. When they began school I thought it was imperative that they live in Columbia. We were and still are the fishbowl of America. I’m so proud to raise my children in a place where skin color and religion are not a reason for judgment.”

McDonaugh’s post drew scores of positive comments like Kim O’Malley’s: “You knew you grew up in Columbia when … Your mom was a Russian Jew and your Father was Irish Catholic and in high school your boyfriend was black and you NEVER experienced racism until you moved to another state as a grown up.”

In 2016, Money magazine rated Columbia as the best place to live in America. The town had been among the top 10 for a decade, providing the kind of external validation Columbia used to get in its early years. “I think we all knew before Money magazine that this was a wonderful place to live,” said Del. Vanessa Atterbeary at the mall kickoff for Columbia’s 50th. She is a lawyer who was born and raised in Columbia, and now represents part of it.

Where It Ends

Where to end this long walk down memory lane?

One way is a drive down Route 108 toward Clarksville. Cross the Middle Patuxent River, still a stream valley, not a lake as originally envisioned. Up the hill on the left is Columbia Memorial Park.

There are four small historic cemeteries surrounded by development in Columbia, but the official Columbia cemetery is not in Columbia at all. In the late 1970s, I once casually asked Jim Rouse, as we chatted before an interview, why there was no cemetery in Columbia. With my armchair psychology, I envisioned some attempt by Rouse to deny death by avoiding its repository. His parents died when he was a teenager and his siblings all died young. Instead, Rouse told me the numbers didn’t work — Columbia land was too valuable for use as a final resting place. Cemeteries are businesses, too.

The 38-acre Columbia Memorial Park opened in 1988. Like many modern cemeteries, the grave markers are ground-level metal plaques. A number of gravesites, like the Rouses’, have low-slung stone benches with the family name.

Five miles from his home on Wilde Lake, Jim Rouse lies buried with his second wife Patty. Jim died April 9, 1996, two weeks before his 83rd birthday and 17 years after he left the company that bore his name. Patty lived on another 16 years, dying March 3, 2012. They lived full lives of great accomplishment.

A short walk back towards the woods is another more poignant gravesite with three markers: Michael David Spear, Judith Sue Spear, Jodi Lynn Spear. They all died Aug. 24, 1990, when the plane Mike was piloting crashed in Boston with his wife and a daughter aboard. Mike had just turned 49 and was president of the Rouse Co., where he had worked since 1967 on the Columbia project, living modestly in a Wilde Lake townhouse and raising their family.

“Mike Spear was a brilliant, compassionate, wise man,” Rouse said. “In many respects, he is irreplaceable.” Many of us would agree with Rouse and wonder what might have happened to Columbia in that decade if Spear had lived.

Jim Rouse and Mike Spear may be buried there, but the story doesn’t end there. There is a brief inscription on Rouse’s grave marker: “We raise up rational visions. What ought to be can be.”

What ought to be, can be. Rouse said it often, and it has been repeated many times by acolytes and admirers. It reflects his optimism and his consistently aspirational rhetoric. Without his aspirations, his noble aims, how could he conceive of building a city — “a garden for growing people” — on 14,000 acres of Howard County farmland?

But Rouse was also a realist. How could a mortgage banker turned shopping mall developer not be tethered to the realities of topography and interest rates, material costs and time?

Time is not kind to stick-built homes, or once fashionable shopping centers. The new structures of Columbia’s heyday are now old; the new families who lived in them are getting old as well.

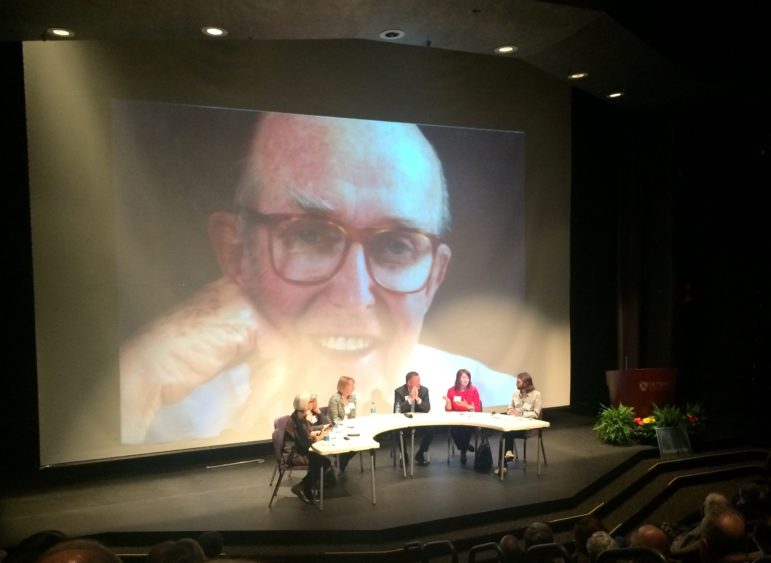

An image of Jim Rouse overlooks the Founders Day panel at Howard Community College May 9, 2017. From left, the moderator, Harvard urban design professor Ann Forsyth, longtime community leader Ethel Hill, Kittimaqundi Community Church Pastor Heather Kirk-Davidoff, former Howard County Executive Ken Ulman, Horizon Foundation President Nikki Highsmith Vernick, and Ian Kennedy, executive director of the Downtown Arts and Culture Commission. Photo: Len Lazarick

Maturation Planning

In her keynote address at Founder’s Day, Harvard professor Ann Forsyth pointed out Columbia was part of the first golden age of new towns in the 1960s. More than 115 planned communities of more than 30,000 people were started around the world. Like Columbia, they are now reaching middle age and need to address their aging.

But now, around the world, “we’re in the midst of another new town golden age,” especially in urbanizing China, where 111 new towns were started in the last decade.

“Columbia still stands out as one of the most admirable new towns in terms of its overall planning,” Forsyth said. Columbia represents an important model, even though Jim Rouse “couldn’t create a General Motors of city building.”

Even in the 1980s, it was recognized that few entities could assemble this much undeveloped land with financiers patient enough to wait decades for a return on their investment.

Yet in the planning literature, Columbia is still one of the most cited developments, Forsyth said, and it could be that again as it deals with “maturation planning,” moving beyond the initial vision. Maturation planning “has not been done very well” most places, she said. “Columbia could be a real leader because Columbia has always been forward looking.”

While Howard County grew around and west of Columbia in the 1990s, the planned community largely expanded commercially on its eastern edge and residentially in River Hill. That village will forever remain disconnected from the rest of West Columbia since Little Patuxent Parkway does not cross the Middle Patuxent.

Except for some garden apartments and townhouses built near the mall on land once planned for offices, Town Center had been largely stagnant till the last few years.

The planner’s job is much harder now. There is no master developer like the Rouse Co. owning thousands of empty acres. With no one else in charge, Howard County government and the Columbia Association are the only institutions with a broader view of the public interest. Neither have the imagination or power Jim Rouse possessed to execute his innovations. The institutions he fostered or imagined are now powers in their own right.

Unlike green pastures and cornfields with a few farmhouses and scattered suburbanites, there are thousands of Columbia residents with firm views on what the town’s future should look like. Pioneers were not voiceless but they had to reach only a few ears, not cajole multiple power centers.

Many of them call on the legacy of Jim Rouse as they choose to interpret it. “One of the unique things [about Columbia] is that it has a founder and a patron saint,” Rouse biographer Josh Olsen told the Founder’s Day audience.

The newest buildings in the Merriweather District with Broken Land Parkway in the foreground and barn at Merriweather Post Pavilion in the middle right. A helicopter photo by R. Scott Kramer for Howard County govt.

Across from the mall, the Little Patuxent Square complex by Costello Construction is downtown’s newest mixed use project, with glassed offices in front, luxury apartments with brick facades and views of Lake Kittimaqundi in the rear, ground level retail and underground parking. On the right, the former Copeland’s restaurant and the parking deck is set for a new office building by Howard Hughes Corp. Photo R. Scott Kramer for Howard County govt

WWJD?

WWJD? What would Jim Rouse do? The gospel according to Jim Rouse is subject to many interpretations. One of the claims is that Rouse did not plan for urban density.

In a long 1986 video interview, Rouse was asked what Columbia would be like in 20 years.

“I don’t believe much in these kinds of distant views of what it” will be, Rouse said. Nevertheless, he went on:

“Columbia will become in 20 years clearly the third major city in the Columbia-Washington corridor. What will be called Columbia — which means Columbia and its developed environs — will be a city of, oh, 300,000 people, maybe more, maybe half a million.” (Howard County’s entire population in 2017 is approaching 320,000.)

He also said there will be six department stores, an opera house, a symphony hall, a stadium for soccer, which “will become by then a very major sport,” said Rouse. And of course, “there ought to be a livelier downtown.”

Rouse at that point had become more famous for developing festival marketplaces in downtown Boston and Baltimore, repurposing the historic Faneuil Hall and the once-decaying Inner Harbor waterfront.

What about the awful prospect of high-rise office buildings? Surely Jim Rouse, of the white stucco four-floor headquarters building on Lake Kittamaqundi, now a Whole Foods, would not have approved. Then you discover his 1966 letter to Connecticut General proposing to erect a 300–500-foot office building, with a restaurant on top where diners might catch a glimpse of the Baltimore or Washington skyline. That’s 25 to 40 stories, 10 to 15 stories taller than anything currently planned. Connecticut General said no, and no more was heard of it.

Would Jim Rouse have approved the stunning new lime green Chrysalis stage in Symphony Woods, its hue called “Greenery,” named Color of the Year by the Pantone Color Institute? Who knows? Except we might note that Michael McCall, who led the work on the Inner Arbor development, worked closely with Rouse in his final career at Enterprise Development. And Rouse, way back when, had painted his own front door yellow without asking the permission of the Wilde Lake architectural committee.

McCall pointed to the results of a three-year Knight Foundation Soul of the Community study done with the Gallup polling folks, who surveyed residents in 26 communities — cities small, medium and large. The study focused on the emotional side of the connection between residents and their communities.

“What attaches residents to their communities doesn’t change much from place to place,” said the study. “While one might expect the drivers of attachment would be different in Miami from those in Macon, Ga., in fact the main drivers of attachment differ little across communities. Whether you live in San Jose, Calif., or State College, Pa., the things that connect you to your community are generally the same,” said the study’s summary of its findings.

“When examining each factor in the study and its relationship to attachment, the same items rise to the top, year after year:

- Social offerings — Places for people to meet each other and the feeling that people in the community care about each other

- Openness — How welcoming the community is to different types of people, including families with young children, minorities, and talented college graduates

- Aesthetics — The physical beauty of the community including the availability of parks and green spaces.”

“Interestingly, the usual suspects — jobs, the economy, and safety — are not among the top drivers. Rather, people consistently give higher ratings for elements that relate directly to their daily quality of life: an area’s physical beauty, opportunities for socializing, and a community’s openness to all people.”

“Remarkably, the study also showed that the communities with the highest levels of attachment had the highest rates of gross domestic product growth. Discoveries like these open numerous possibilities for leaders from all sectors to inform their decisions and policies with concrete data about what generates community and economic benefits.”

Columbia is already way ahead on the most important factors. Of course, McCall sees the Chrysalis project, and overall revamping of the Merriweather District, contributing to both socializing and aesthetics, and an appeal to Millennials. A vocal minority of Columbians disagrees.

Terri Hill is not thrilled with some of the new downtown development just beginning in the Merriweather District, the new MedStar building for one. She believes Columbia has “the best of urban living and the best of suburban living.”

“Columbia doesn’t want to be Bethesda,” Hill said. “If Columbia is not urban enough for you, then go move to another place.”

Thousands of property owners of homes and businesses must also be encouraged to update, improve and rehabilitate their aging structures, or even forced to do that if the decline is bad enough. A healthy, 40-year-old tree is a nice amenity; a 40-year-old house that has been neglected is not. The village associations and CA have some power to force upkeep, and CA is studying taking over responsibility for the business parks and commercial areas where Howard Hughes Corp. still has nominal control, though not ownership.

There are concerns that property values are at risk, but a 2013 CA study of market trends found: “Residential sales prices in Columbia’s villages have fared well in the past decade even with the ‘great recession’ of 2008 to 2009. … In general, the percentage increase in average sales prices for the Columbia villages were equivalent or exceeded those for Howard County for the years between 2001 and 2007 and fell less steeply than those in the county in 2008 and 2009.”

A more recent 2017 study for the always-struggling Oakland Mills Village Center and environs found the housing market there was “at a stage of general value stability relative to the surrounding regional market, with prices moving more or less in tandem with other locations.” Home prices were sometimes lower there because the houses were smaller.

There is wild talk of a used car lot at Route 108 and Red Branch Road, and how awful that might be. Presumably, those residents get around town on foot or by bike and are appalled by the huge Apple Ford complex on Snowden River Parkway, used cars and all.

With little but acreage in downtown (and some in Gateway) in control of Howard Hughes, the county has taken the lead. First steps have been taken to make Gateway into an “innovation center.” It is now as bland and un-Columbia-like as any office park in the region, but could it be transformed into another Columbia neighborhood with mixed uses on some still-vacant lots, or redevelopment of one-story flex office buildings? The county is also asking the state to look at better access from I-95.

There is even more concrete hope for the Long Reach Village Center, with more apartments and townhouses. Orchard Development Corp. is taking the lead as it has for Toby Orenstein’s part of Merriweather District.

While the town may be turning 50, and a quarter of its residents are 55 or older, another quarter of its residents are 19 or younger. There’s a lot of young blood in the aging new town if they can be enticed to stay here.

The Founder’s Day event at Howard Community College concluded with a short video clip from Jimmy Rouse offering the typical Rouse-like uplift.

His father, said Jimmy, “was not into being a hero or saint. He was into the growth of human potential.”

“He was a deeply spiritual person” who believed that “we are co-creators with God,” Jimmy told several hundred people in the Smith Theatre, mostly an over-50 crowd.

“You all are co-creators with him of Columbia. It is for you all to go out and create this great city.”

Columbia has been for me and many a great place to live, work, thrive, raise a family and even die. Can it be that great city in the future?

It’s in our hands and in the hands of a generation to come.

Len Lazarick

Len Lazarick (Len@MarylandReporter.com) has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics, and a political columnist for The Business Monthly.

Part 2 focuses on the businesses of Columbia as an essential part of the plan.

Part 3: Shopping and Retailing at the Heart of the Columbia Plan

Part 3 examines the central role of shopping and retailing for the development of the Columbia plan. With changes in both lifestyles and retailing — and a couple of poor locations — the village centers did not always work out as planned.

Part 4: Media in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest

Part 4 examines the role of media in creating the community, primarily newspapers, and in particular, the Columbia Flier.

Part 5: POLITICS: The Shifting Weight of Columbia Power

This is the fifth part in a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. This month looks at the shifting dynamics of political power in Howard County because of the presence of Columbia and its largely Democratic voters.

Part 6 EDUCATION: Schools Were Crucial Then and Now

Part 6 examines the planning and transformation of a small, rural, recently desegregated school system with middling rankings to one of the best school systems in the country. Howard County now has 76 schools with 54,000 children and 4,100 teachers, and they face the challenges of diversity, particularly in its urban core of Columbia.

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help. The opening of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics in 1973, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

Part 8: RELIGION: Interfaith centers sought to bring congregations together

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia. While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all.

Part 9 ENVIRONMENT: Respecting the Land While Building a City

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys. The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were? Because they were not going to stay that way for long as suburban development spread from Baltimore and Washington along the new interstate highways.

Part 10: ARTS at the Heart of the New Town

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first structures built before Columbia even had its first residents. Now it is being redeveloped and is at the center of the Merriweather District that is the core of Columbia’s new downtown. But Merriweather is only part of the arts scene in the planned community.

Part 11: Recreation and the Role of the Columbia Association

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Association. As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them. As Columbia looks to the future, CA not only wants to keep the pools and athletic facilities open, but to keep Jim Rouse’s vision alive.

Recent Comments