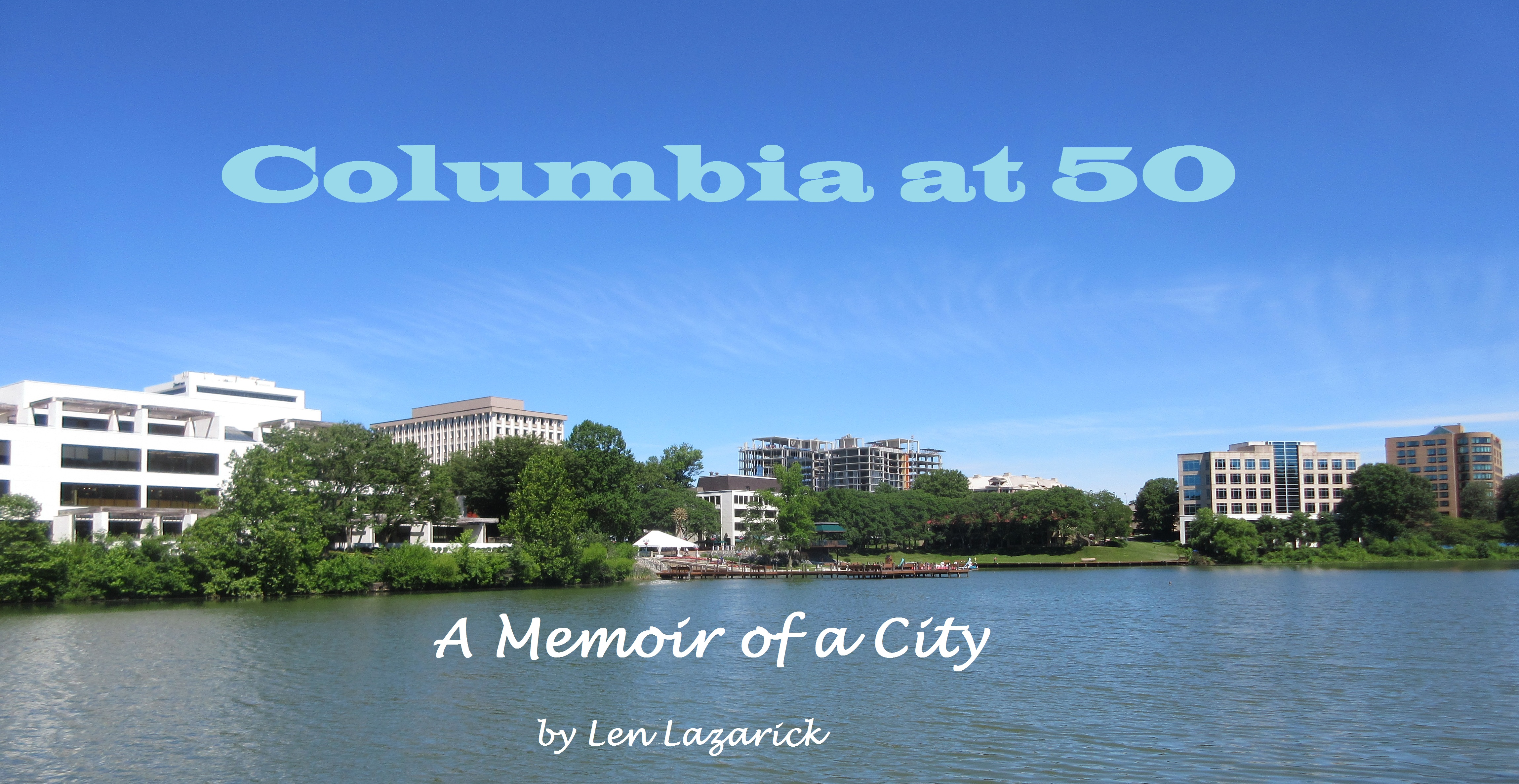

This is the eighth part in a series of 12 monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration in June 2017. It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that, was published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom.© Len Lazarick 2016

Links to all the essays are at the bottom of this story. They have also been compiled in a 200-page book available here.

By Len Lazarick

I could hear the chanting from the Sabbath services of Temple Isaiah down the hall of The Meeting House in Oakland Mills as our family gathered in the Catholic chapel for the baptism of Sarah Kelley Lazarick on Dec. 1, 1979.

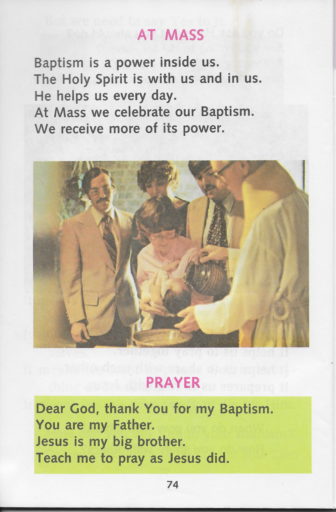

Father Bennet Kelley put this photo of Sarah Kelley Lazarick’s baptism in a catechism he wrote for children published four years later. From right, Father Kelley, Len Lazarick, Maureen Kelley holding Sarah, godparents Kathy Lazarick and Kevin Kelley.

How fitting that the Torah’s God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob was being worshipped at the same time and place as the baptism of Sarah, the name of Abraham’s wife and Isaac’s mother. I had called repeatedly on the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob after her difficult birth five weeks before as the distressed infant was whisked away in an ambulance from Howard County General Hospital to Saint Agnes Hospital’s Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, as I described in part 7.

Now home and healthy, Sarah was being baptized by her great uncle, Father Bennet Kelley, C.P., as she wore the same family christening gown that the priest had worn 57 years before.

I really liked the idea that Sarah was being brought into the church in a welcoming community where Christians of different denominations and Jews as well shared space and ideas.

This was unheard of when I was growing up. My mother was Presbyterian, and she and my Catholic father were married in the rectory and not the church because it was a “mixed” marriage.

It was not until the mid-1960s that a shared facility like this was even conceivable for Catholics, when the Second Vatican Council adopted the Declaration on Religious Liberty. That was largely due to the long-suppressed work of Jesuit theologian John Courtney Murray, who taught at the Woodstock theological seminary just 14 miles away across the Patapsco River, where he is also buried. The declaration opened the way to broad ecumenical cooperation and interfaith dialogue.

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia.

While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all. There was no expert on religion in the original planning group that included expertise in so many other fields — education, health, government, sociology, economics. Rouse may have been his own expert on religion.

Rouse’s Religious Motivation

As Josh Olsen documents in his essential biography of Rouse, Better Places, Better Lives, religion was at the core of Rouse’s motivation to build a new city, starting with a 1961 talk he gave on “Christianity and the American City.” Like my mother, Rouse and his wife Libby were practicing Presbyterians, and Jim Rouse was even an elder at his Baltimore church. In the 1960s, as Columbia was being conceived and planned, the Rouses were also regular participants in the Church of the Savior in Washington, D.C., a nontraditional congregation that strongly embraced the social gospel of Jesus.

In 1964, as the acquisition of land was being announced, Rouse and his staff invited the local churches in to help drum up local support for the project’s zoning, but they approached the national denominations as well.

This set off a long, complicated and sensitive process of talks and negotiations. Letters and memos went back and forth, filling three thick volumes of documents at the Columbia Archives.

The Protestant groups took the lead, some more enthusiastic than others. This culminated two years later with the creation of the Columbia Religious Facilities Corporation on May 31, 1966.

“It was the Protestants who first developed the interfaith center concept,” said Carolyn Arena, a member of St. John the Evangelist Catholic parish who served on the board of the Religious Facilities Corporation for years. Arena is putting the final touches on a book she co-edited with the late Betty Martin on the interfaith experience in Columbia, with contributions from 40 different people of various congregations.

Howard Research and Development, the Rouse subsidiary building Columbia, was willing to sell the land for churches at bargain prices.

“The village centers were going to be the center of life in Columbia,” Arena said, and that’s where the churches wanted to be. In the First Village, as it was called before it was dubbed Wilde Lake, HRD wanted to put the churches on a high point west of the village center. The churches wanted 10 acres to the east, which they finally got.

The opening of the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center in September 1971. Photo courtesy Columbia Archives.

Catholics Finally Join

While there had been Catholic representatives at some of the meetings, the Catholic Church was going through immense changes in liturgy and outlook after Vatican II, and the Church wasn’t committed to participate in the joint facilities. Then, in 1967, Wallace Hamilton, Rouse’s director of institutional planning, wrote, “Hell has frozen over — the Catholics agree to join.”

The Unitarians with some trepidation came on board, and the first Jewish congregations in Howard County also agreed to join. (The few Jews who lived in Howard County had been mostly merchants in Ellicott City.)

Cardinal Lawrence Sheehan also agreed to foot a third of the costs of the facility that was to be built in a few years.

According to Hamilton, in the planning process for the churches, “The one conviction the committee held through thick and thin was that they were not going to build a cathedral or any other ceremonial bricks and mortar.”

A brochure for Columbia’s first residents explained that religious services would be held for several years at Slayton House, the community center that would be the launching pad for other faith communities in future years.

“This may seem, at first glance, to be a haphazard and stopgap arrangement,” but it was the outcome of three years of planning, the brochure said. This was part of “an adventure in new forms of congregational involvement with the life of a community, new forms of ministry, new forms of interdenominational and interfaith cooperation — all in the hope that it will lead the people and the congregations of Columbia to explore new imperatives of God’s relationship to man and men’s relationship to each other.”

There was a practical and financial reason for the decision. “Sometimes up to 4/5 of total income [of a congregation] are spent on the building and maintaining of a physical plant — a church or synagogue building.”

Monsignor Richard Tillman still celebrates the occasional Sunday mass in Room 1 of the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center as he did on Jan. 22. Photo by Len Lazarick

Not a Cathedral

Certainly no cathedral was envisioned. The architecture of the first building, the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center that opened in 1971, reflected the architectural equivalent of the lowest common denominator for this motley crew of priests, ministers and rabbis in a hodgepodge of congregations worshipping under the same roof. It still looks more like a utilitarian office building than a church. Inside, when it first opened, it had the same nondenominational feel, and to an extent it still does.

For Catholics, and perhaps others, the worship space was the most unsettling in what was to be their permanent home. Room 1, the largest space in Wilde Lake, was as generic as its name. No statues, no pews, no kneelers, no stained glass, no marble, and perhaps most jarring for those who had only recently switched to worshipping in English rather than Latin, there was no tabernacle, the typically ornate repository for the Holy Eucharist. There were just chairs, an altar and a cross.

No need to genuflect, folks; Jesus in the form of bread wafers was stored in a tabernacle across the hall in a small chapel.

Room 1 and Room 4 were deliberately utilitarian so they could be used by other faith traditions and for community meetings and events, as they often were.

Into this space in June 1977, 10 years after Columbia and St. John the Evangelist parish opened for business, walked its new pastor, a 37-year-old priest named Richard Tillman.

When he got the call from the archdiocese at the South Baltimore parishes he was serving, “I was really shocked” at the unexpected assignment, Tillman recalled in a January interview. He had participated in the Central Maryland Ecumenical Council, but he had only served in traditional parishes. He was also a bit surprised that the priestly personnel director asked him how his celibacy was going — the vow not to marry.

“They were looking for some stability,” said Tillman. The first pastor, John Walsh, had left the priesthood to marry, and the current pastor, George Cora, was about to do the same.

If the church was looking for stability — it turned out Archbishop William Borders had suggested him for the job — they got it in spades with Tillman. He would serve 33 years as pastor, four times as long as most Catholic pastors, doubling the parish in size to 3,000 families.

“They knew I liked it here,” Tillman said. “Once I got here and found out what was going on, I liked it here.”

Catholic priests had dealt with interdenominational ministry as chaplains in the military and at public universities, but Columbia was a special case.

The 1970s and ’80s were perhaps the high points of interfaith cooperation and what was then known as the Columbia Cooperative Ministry, which was involved in social ministry as well, such as the Interfaith Housing Corp. it set up.

The Catholics were operating out of both Wilde Lake and The Meeting House in Oakland Mills, which opened in 1975. In Wilde Lake, there was St. John Baptist Church, an African-American congregation of Baptists; St. John United Methodist/Presbyterian Church, already interdenominational and home church for Jim Rouse and his second wife Patty; and a Lutheran congregation. Oakland Mills had other Christian and Jewish congregations, as it still does today.

It was in The Meeting House that I experienced my first Bat Mitzvah, the Jewish coming of age ritual for the daughter of a friend; decades later, in the same room, my daughter Sarah would be married at a Catholic mass celebrated by Father Tillman. That day, when I showed Tillman a picture of him and Sarah taken after her first communion in Wilde Lake, he went into the sacristy and found the same multicolored stole he was wearing that day 20 years before.

Sharing With Other Faiths

Tillman remembered how, in his early years in Wilde Lake, “four or five of us pastors would get together to discuss our sermons,” based on the same readings from the standard lectionary. “Faith has that interfaith dimension built into it,” Tillman said, and in his own homilies, he would bring in perspectives from other traditions with “different approaches to faith.”

The interfaith centers were a good solution to the problem of startup congregations in a new community. But as the congregations prospered, they began crowding each other and outgrowing the space,

Rev. Dr. Robert Turner arrived from Cambridge, Mass., on May 1, 1993, to pastor St. John Baptist Church, in hopes of working with others. “I was intrigued by this concept of the planned community, and even more intrigued by the interfaith centers,” Turner said in a January interview.

But once he arrived, he found that there was little shared ministry beyond an occasional exchange of pulpits. And as the ministries for his own congregation grew, there was increased competition for space in Wilde Lake, not just on Sundays but in the evenings as well.

“The space was impeding our growth,” and in 1997, his congregation left Wilde Lake for a sojourn in a Route 108 office park.

His was not the last religious community to find a home in Columbia’s first business park.

10 Villages, 4 True Interfaith Centers

In the 10 villages that make up Columbia, there are only four true interfaith centers where two or more congregations share the same facilities.

The near-vacant Long Reach Village Center, which the county is trying to redevelop, comes alive on Sunday mornings for three energetic, praiseful services in music and word at the Celebration Church, a successor to the Long Reach Church of God founded by Bishop Robert Davis and now with his son Robbie Davis as the lead pastor.

There were two congregations originally slated for the Long Reach site, but after the other dropped out, the church opened in 1973. It now has 2,500 predominantly African-American members and a day school.

In 2005, after a long struggle, the Gathering Place, the River Hill interfaith center, opened with two congregations — the Emmanuel Messianic Jewish Congregation, which observes Jewish traditions but accepts Jesus as the messiah; and the Oak Ridge Community Church, which worshipped in Howard County schools for years. Emmanuel first bought the land from the Rouse Co. in 1998.

At Kings Contrivance Village Center, instead of one facility, there are two churches on one site. The Orthodox Church of St. Matthew, like other startups, made a stop in Slayton House, then built its own church, in modern style but resplendent with icons and murals, where it began worshipping in 2007. Its Divine Liturgy on Sundays is chanted in English but with typical Eastern tonalities and abundant incense. Next door in a separate building is Cornerstone Church, a predominantly African-American congregation. They share a parking lot.

The Owen Brown Interfaith Center is now the most eclectic of the centers. Opened in 1984 — nine years after The Meeting House — it became the permanent home for a United Methodist congregation and the Unitarian-Universalists, a group that honors all religions. Both had been renting space in Columbia. It now also includes small congregations of Muslims, Jews and followers of Sathya Sai Baba, an Indian who embraces many religions.

In 1986, the Columbia Flier did a survey that found that only 44% of Columbians who chose to worship at all worshipped in an interfaith center.

Outside the Interfaith Centers

Many of the others went to the churches that existed before Columbia. Perhaps the oldest is Christ Episcopal Church on Oakland Mills Road at Dobbin, sometimes called Old Brick for the 1809 structure that is the oldest church building in Howard County. There has been a church on this site since 1711, but like many a church serving Columbia, the congregation that worships at the newer, larger sanctuary on the grounds bills itself as “diverse, multicultural.”

Catholics looking for a more traditional experience have long flocked to one of the oldest parishes in Howard County, St. Louis, in Clarksville. It grew out of the private chapel at Doughoreagan Manor, just north of Columbia, the country home of Charles Carroll, the only Catholic signer of the Declaration of Independence. The chapel was built in the 1700s when it was illegal to build a Catholic church in the colony.

Responding to Howard County’s growth, including the nearby village of River Hill, Columbia’s last, St. Louis is now on its fourth church building, each one larger than the last. The 2006 church that serves 4,200 families is more cathedral-like than any worship space in Howard County. The stained glass windows were brought from the Basilica of the Assumption in Baltimore, the first cathedral in the United States, after its original plain windows were restored.

Within Columbia itself, there are likely more worshipers in business parks, schools and community centers than there are in the interfaith buildings.

A choir singing in several languages leads the service at Bridgeway Community Church on Jan. 15. Photo by Len Lazarick.

Bridgeway

The largest and most remarkable, with a reach far beyond Columbia, is Bridgeway Community Church, operating out of a large complex on Red Branch Road in the former headquarters of Head Sports.

On any Sunday morning, the cars stream in off of Route 108, filling three parking lots; congregants occupy most of the seats for three services in a theater-like auditorium that seats 1,047 people. On a recent Sunday, the hall rocked with song in five languages, with a choir as ethnically diverse as the people who packed the hall.

“Our goal was to be a multicultural army in Columbia,” said Rich Becker, a co-founder of the church nearly 25 years ago with Senior Pastor David Anderson. “We wanted to work hard to create a church that people wanted to come to … a place that wouldn’t be boring.”

The church specifically embraces a “multicultural ministry,” the title of a book Anderson penned. It followed a book he wrote called Gracism, which executive pastor Dave Michener explains is “the opposite of racism.” Anderson is African-American, Becker and Michener are white, reflecting the deliberate ethnic mix of their ministry, now staffed by 40 people in many shades from pale pink to dark brown.

“There were a lot of naysayers [to us] as a multicultural church,” Michener said. The congregation now includes people from 52 countries and about half are black — American, African and Caribbean.

“I get to see God in many different groups,” Anderson told the congregation on the weekend of Martin Luther King’s Birthday.

Bridgeway had modest beginnings. Like many of Columbia’s first congregations, it started with services in Slayton House, where it stayed for five years. There were 110 people on hand that Easter Sunday in 1992. “The following week we had 30 people,” Becker recalled. It was slow going.

Both Anderson and Becker had to work outside jobs to support themselves while they built the church.

The diversity they were seeking to build in their church is “one of the main reasons that we chose to be in Columbia,” Becker said. When people come to worship, they want to make sure “they see someone who represents them.”

The church is nondenominational, but its beliefs are standard Bible-based evangelical Christianity. “We actually talk about real life,” in our sermons, said Michener. “We want people to have an experience of community,” and “we want to remove any unnecessary barriers” for people coming to church.

Michener said that in addition to the thousand present in the auditorium, as many as 2,000 watch online, from different countries as well. (With the advances in Internet technology and reduced equipment costs, many other congregations live stream their services, including the Catholics in Wilde Lake.)

Anderson also has a daily radio show broadcast, “Real Talk with Dr. David Anderson,” from a fully equipped digital studio in the church complex, and he does TV shows as well from the studio.

Michener said they are getting ready to launch other campuses for the church. But “the bigger we get, the smaller we want to feel,” he said.

Besides traditional churches and synagogues that have grown around Columbia, there are more places of worship in business settings, such as Bethany Church on Dobbin Road in a former warehouse space once occupied by Cornerstone Community Church. “We’re here to build the kingdom of God,” said its young pastor, C.J. Matthews, who has ambitious plans to build up the church from its 105 members.

Not far from Bridgeway, in flex office space off of Rumsey Road, is the Maryum Islamic Center, founded by Imam Mahmoud Abdel-Hady, who led the larger Dar-al-Taqwa mosque on Route 108 for 19 years. He preaches to about 100 men and women at Friday prayer. It never would have occurred to the early Columbia planners that Muslims would need a place to worship here.

The noon “contemporary” service at St. John the Baptist Church Jan. 22. Photo by Len Lazarick

‘Missed Opportunity’

The Rev. Robert Turner

Before Pastor Turner and his growing Baptist congregation left the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center 20 years ago, “we looked for some space in Columbia, but we couldn’t afford five acres in Columbia.” The Rouse Co. was unbending. Turner had even approached Jim Rouse, long gone from the firm that bore his name, for his help. But Rouse told him, “He intended for these interfaith communities to solve the problem for themselves.”

That’s when Turner moved the church to the Route 108 business park. It eventually bought 40 acres in Ellicott City on Marriottsville Road across from Turf Valley at a price “for less than five acres in Columbia,” Turner said. But the county would not extend water and sewer to the property.

In time, the Howard County school system approached Turner as it hunted for a school site in Ellicott City. It was willing to swap 10 acres in Columbia for his 40 acres and some cash.

At the corner of Tamar Drive and Route 175, St. John Baptist built the most visible church on new town land, a structure that actually looks like a church, outside and in, steeple and all, with pews and pulpit. It opened in 2009.

Yet his leaving the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center 20 years ago “was bittersweet. I really wanted to do some creative things with different denominations.”

Turner has been a leader in the formation of PATH, People Acting Together in Howard, a group of congregations mostly in Columbia that includes Catholics, Protestants, Jews and even the Muslims at the Maryum Center. They hosted a meeting at the Wilde Lake Interfaith Center in January to push for making Howard a sanctuary county — as both Turner and Abdel-Hady urged their congregations to do.

Yet, “there’s still no shared ministry,” Turner said. “I think that is a missed opportunity.”

“They are so wrapped up in fulfilling their individual faith community mission that they don’t spend time in exploring a shared faith vision. There isn’t a sense of ‘we.’”

And while the congregations focus on their own communities, there is also a consciousness of the larger populace in Columbia that is un-churched. “Our biggest competition in Columbia is athletics” on Saturday and Sunday, Turner said.

Catholics have largely taken over the Wilde Lake center with an influx of Hispanics and Latinos over the past decade. In addition to the center’s three masses in English each weekend, three masses are celebrated there in Spanish, with the service for the small St. John United Methodist/Presbyterian congregation sandwiched in between. (After the 2008 recession hit, the Methodist/Presbyterian group abandoned plans to build a freestanding church — cross and all — next to the current facility.)

Remnants of interfaith sharing remain. At mass on Sunday, Oct. 2, I

noticed that the Stations of the Cross had been taken down in the room — 14 modernistic wood carvings evoking Jesus’s Way of the Cross that were a recent addition to the bland brick walls. At choir practice the next day, I noticed the large crucifix over the altar and the one statue of the Holy Family had been removed. Then it hit me — it was Rosh Hashanah. The Catholics again were accommodating the Jewish congregations that balloon for the High Holy Days.

While the realities of religious division remain, there is still — in Columbia and in many other places across the land — that spirit of interracial and interfaith diversity that bloomed in the Civil Rights movement and Columbia’s early days.

We heard again at Bridgeway on that MLK Birthday Sunday the conclusion of Martin Luther King’s 1963 speech at the Lincoln Memorial, in his own voice — a speech, like other King speeches, that Jim Rouse had circulated among colleagues and friends in the 1960s.

“From every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

Len Lazarick

Len Lazarick ([email protected] ) has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics, and a political columnist for The Business Monthly.

Part 1: How the ‘garden for growing people’ got planted and grew

In this first installment, Len Lazarick looks at how a new town with ambitions to be a real city “not just a better suburb” came to be on 14,000 acres of Howard County farmland with lofty goals that faced some hard realities.

Part 2: Working in Columbia: Its Downtown and Business Parks Went Up and Down With The Economy

Part 2 focuses on the businesses of Columbia as an essential part of the plan.

Part 3: Shopping and Retailing at the Heart of the Columbia Plan

Part 3 examines the central role of shopping and retailing for the development of the Columbia plan. With changes in both lifestyles and retailing — and a couple of poor locations — the village centers did not always work out as planned.

Part 4: Media in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest

Part 4 examines the role of media in creating the community, primarily newspapers, and in particular, the Columbia Flier.

Part 5: POLITICS: The Shifting Weight of Columbia Power

This is the fifth part in a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. This month looks at the shifting dynamics of political power in Howard County because of the presence of Columbia and its largely Democratic voters.

Part 6 EDUCATION: Schools Were Crucial Then and Now

Part 6 examines the planning and transformation of a small, rural, recently desegregated school system with middling rankings to one of the best school systems in the country. Howard County now has 76 schools with 54,000 children and 4,100 teachers, and they face the challenges of diversity, particularly in its urban core of Columbia.

Part 7: HEALTH CARE: Planning for a healthy community — an innovative HMO, a hospital fight and the quest for wellness

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help. The opening of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics in 1973, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

Part 8: RELIGION: Interfaith centers sought to bring congregations together

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia. While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all.

Part 9 ENVIRONMENT: Respecting the Land While Building a City

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys. The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were? Because they were not going to stay that way for long as suburban development spread from Baltimore and Washington along the new interstate highways.

Part 10: ARTS at the Heart of the New Town

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first structures built before Columbia even had its first residents. Now it is being redeveloped and is at the center of the Merriweather District that is the core of Columbia’s new downtown. But Merriweather is only part of the arts scene in the planned community.

Part 11: Recreation and the Role of the Columbia Association

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Association. As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them. As Columbia looks to the future, CA not only wants to keep the pools and athletic facilities open, but to keep Jim Rouse’s vision alive.

Part 12 Conclusion: A 50-year-old town faces its future

Veteran journalist and longtime resident Len Lazarick wraps up by looking back over the past 50 years and looking forward to Columbia’s future. All 12 chapters have now been published as a 200-page book.

Recent Comments