This is the seventh part in a series of 12 monthly essays leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration in June 2017. It ran first in The Business Monthly, circulating in Howard and Anne Arundel counties, and after that, was published here on MarylandReporter.com and by our partner website, Baltimore Post-Examiner.

The copyright is maintained by the author and may not be republished in any form without his express written consent. Comments and corrections are welcome at the bottom.© Len Lazarick 2016

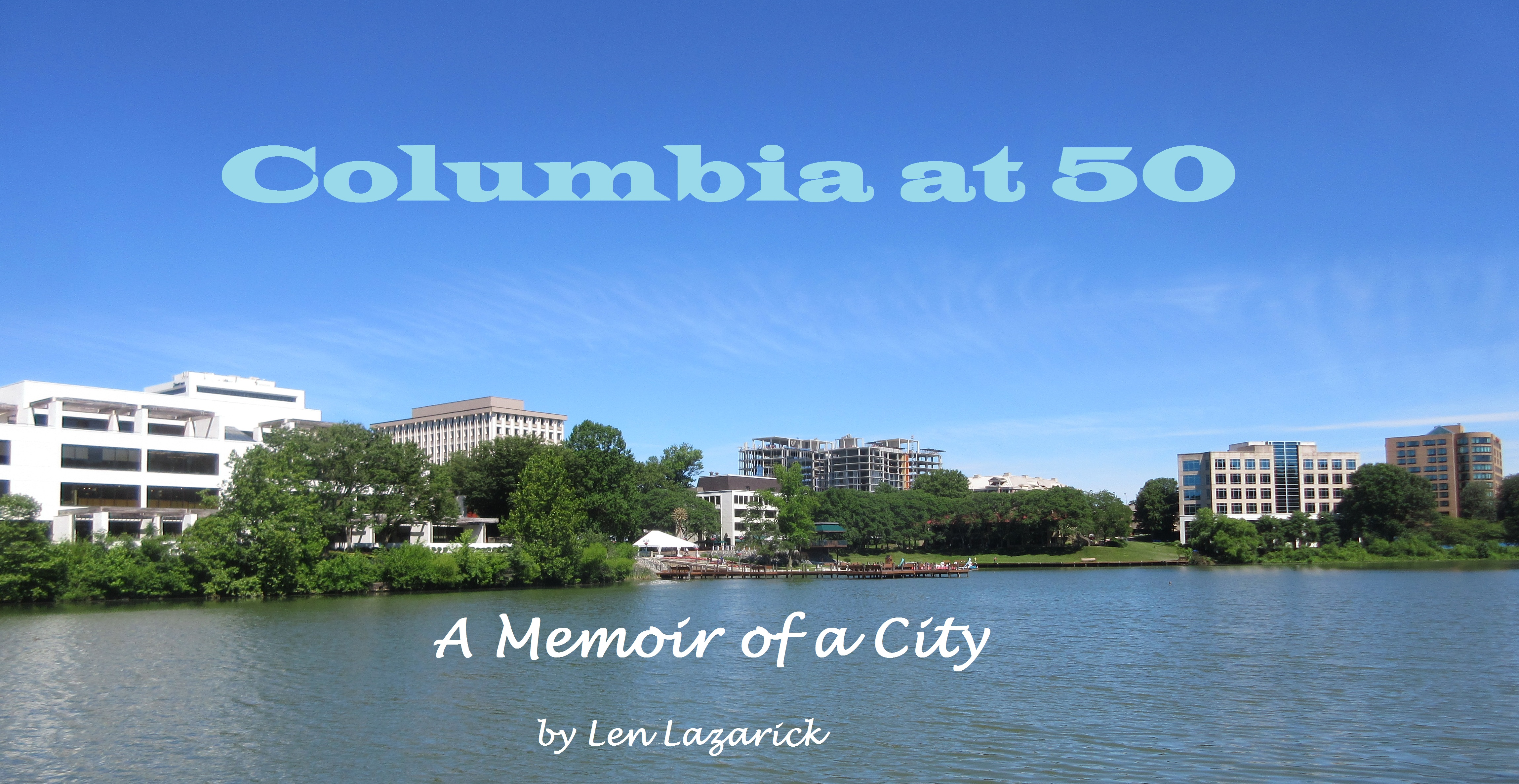

Links to all the essays are at the bottom of this story. They have also been compiled in a 200-page book available here.

By Len Lazarick

Jim Clark lay unconscious in a wheat field on his farm off of Route 108 on the morning of March 28, 1947. The 28-year-old wartime glider pilot had tripped while planting clover, and the drill the horses were pulling had knocked him out as they dragged him across the field.

“The disk had cut my face badly with one eye severely hurt … my back had been cut badly by the stones in the soil. The steel wheel had run against my left arm and caused a large gash,” the farmer who would become Maryland Senate president in 1979 recounted in his autobiography that I helped edit 20 years later.

A young farmhand eventually found Clark, his wife Lillian covered him with blankets as he began to go into shock, and she summoned a local physician. The doctor “knew immediately that I had to go to the hospital, so he put me in his car and took me to Montgomery County Hospital at Sandy Spring, where they gave me emergency care,” Clark wrote.

It’s hardly unusual for a rural county in Maryland or anywhere in the U.S. not to have a hospital. It would be another 26 years before Howard County would get its own, just two miles south of the Clark family farm, with Lillian eventually serving on its board.

The opening of that hospital in 1973, first called the Columbia Hospital and Clinics, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

The hospital in Columbia as it looked when it opened in 1973. Courtesy of Columbia Archives

Planning for Health Care

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help.

In the early 1960s there was still a limited number of doctors in Howard County, and anyone needing inpatient care would go to Montgomery General Hospital in Olney or to Saint Agnes Hospital on the western edge of Baltimore. But a time of change in American health care was beginning that would continue to evolve for the next 50 years. Columbia was poised to explore novel options.

Paul Lemkau, a mental health expert from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, had been in Rouse’s early planning group. At the urging of Jim Rouse, leaders at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions became interested in delivering health care to the new planned community that Rouse projected would have 100,000 people by the early 1980s.

But first they had to overcome the objections of their own medical staff, who feared that the relatively affluent residents of the new town would draw resources from their inner city hospital, distract from its role in teaching and research, and not attract the best physicians.

The project gained enthusiastic support and, most importantly, financing from the Connecticut General Life Insurance Co., which had provided the money to buy the land and develop Columbia. Connecticut General was particularly interested in participating in a new trend in health care delivery, as Hopkins planned to develop a health maintenance organization, a prepaid group-practice of medicine that would emphasize prevention and easy access to health care over the more traditional fee-for-service model. In 1969, they launched the Columbia Medical Plan (CMP), which would last for three decades.

HMOs, as they were dubbed, were popping up all over the country, offering comprehensive care employing salaried physicians in a single facility. I had already been a member of the Harvard Community Health Plan when I lived and worked in Boston, and felt the CMP was another attractive feature about our move to Columbia in 1973 — especially since the group was connected to another world-renowned medical school, Johns Hopkins.

Slow Growth

As noted in earlier essays in this series, the 1973 Arab oil embargo and a recession accompanied by inflation and high interest rates had played havoc with the Rouse Co.’s economic model. Sales of housing and land in Columbia slowed, pushing the entire project toward bankruptcy.

Little did I know in 1973 that, just five years after it got started, the Columbia Medical Plan was falling short of its membership goals and financial plan. The problems were spelled out in detail in the New England Journal of Medicine by two Hopkins docs intimately involved with the planning and operation of CMP, Robert Heyssel and Henry Seidel.

“By 1974, Columbia was expected to have a population of 64,000, and the plan a membership of 32,000,” the doctors wrote. “In fact, by mid-1976, Columbia’s population was 40,000, and the plan’s membership a bit in excess of 19,000.”

“The population base was simply not large enough,” they concluded.

Contributions to support the research and writing of this series on Columbia are tax-deductible because MarylandReporter.com is an IRS designated nonprofit news website. If you would like to help fund this series and its eventual publishing as a book in June, please use the donate button to the right. Thank you.

Carrying On

Despite early losses — $1 million in just its first three years — the Columbia Medical Plan continued to grow as the population rose, though at a slower pace than originally projected. In 1982, CMP was acquired by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Maryland. By 1994, it had grown to 76,500 members in Howard and surrounding counties, including 3,000 Medicaid recipients who had been added the year before. This turned out to be the plan’s peak enrollment.

A new chief operating officer at that time told the Baltimore Sun: “This organization embodies health care reform.”

In 1997, data from the National Committee for Quality Assurance led U.S. News and World Report to rank CMP No. 8 among the top 10 HMOs in the U.S.

At that time, CMP had 120 full-time physicians and another 400 employees. Some of that “quality” was attributed to the managed care and tracking systems for patients in the group practice. By then the plan was occupying two large buildings at Twin Knolls North.

The Columbia Medical Plan in the late 1970s after it moved down Little Patuxent Parkway from the hospital. Photo courtesy of Columbia Archives.

25 Years With the Plan

For 25 years, I, my wife and the two daughters born in Columbia were part of one of the best health maintenance organizations in the nation, seeing great doctors, nurses, nurse practitioners and other health professionals. Early on in 1977, I got to meet one of the great orthopedic surgeons in town, Dr. Eugene “Pebble” Willis. He set my broken wrist one night after I slipped on ice as I was cleaning off my car to go to a meeting.

There were safeguards in the plan, too. When I was diagnosed with gallstones after some pain, one plan surgeon, a former Army doc, recommended removing my gallbladder. That was back in the day when that involved a major incision in the abdomen, not the laparoscopic surgery common today. I consulted the head of the surgery department. He told me that if the gallbladder wasn’t giving me a lot of trouble, there was no need for surgery. I’ve still got my gallbladder and an occasional twinge.

My wife, Maureen Kelley, remembers the great pediatric care our daughters Sarah and Rachel received. And there was no schlepping to the Giant or Walgreens for a prescription, with a pharmacy in the same plan facility.

In 1993, I had my most intense medical experience that started with a visit to Urgent Care and high blood pressure. When my heart produced an irregular EKG, I was shipped off to Howard County General Hospital, which by that time had its own cardiac care unit. After a day or two there (memories are vague), I was carted off to Johns Hopkins in East Baltimore for a cardiac catheterization; nothing requiring further surgery in my heart was found. Still grogged up from the anesthetic, I did get to experience being a brief case study on grand rounds, with an esteemed faculty cardiologist explaining my condition to a group of young docs.

A year later, Sarah developed a collapsed lung playing field hockey that eventually led to a two-week stay in an adolescent unit at Hopkins.

Both of these intensive hospital stays, including ambulance rides, multiple tests and surgical procedures, cost virtually nothing except for incidentals like phones. I do recall seeing an itemized accounting for Sarah from Hopkins that was more than $15,000.

Unraveling

Things began to unravel at the Medical Plan in the late 1990s, and the storyline becomes confusing as the names of the principal players change. Health insurance and health care in general were then and still are in desperate search of ways to reduce costs and improve coverage.

In 1998, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Maryland and Washington became CareFirst, and that insurer merged the Columbia Medical Plan with its Freestate health maintenance organization. The Patuxent Medical Group was delivering the medical services, and by 2000, what had been the Columbia Medical Plan was down to 60,000 members and losing patients as they sought greater choice of physicians. As physicians and staff were laid off, waits got longer and more members left.

Of course, though thousands of Columbians had joined the Columbia Medical Plan over the years, many thousands of others had signed up with traditional insurance plans and saw the hundreds of doctors who practiced in Columbia and Howard County.

Almost all of these docs, in whatever kind of practice, would have privileges in the county’s one hospital, Howard County General. That there would be just one hospital in Howard County was a matter of intense dispute for more than a decade.

The Hospital

The Columbia Medical Plan fell under the umbrella of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics Foundation, run by Hopkins with Connecticut General financing. As initially conceived, the hospital was primarily to care for members of the Columbia Medical Plan, with some limited number of beds available to the wider community.

This was tough medicine to swallow for the folks outside Columbia. The county was providing the town’s public schools, its public library, maintaining its public roads, its police and fire protection. Yet, a major community institution the county lacked, a hospital, was to be off limits to those who would not join the new-fangled health maintenance organization. So much for Columbia being a boon to those outside it.

This led at first to two other competing proposals for hospitals in Howard County. One came from the Sisters of Bon Secours, a French-born health care religious order whose U.S. motherhouse is still in Marriottsville. It operates Bon Secours Hospital in West Baltimore.

The other was from Lutheran Hospital, also in Baltimore, with a plan to build a hospital on Grey Rock farm owned by Charlie Miller, one of the Republican commissioners who had approved the plans to build Columbia. The farm sat next to the library on Frederick Road in Ellicott City.

The sisters had acquired land north of Ellicott City for a hospital, nursing home and senior housing. Back in 1973, as the Columbia hospital was about to open, the sisters had put together a proposal for the second hospital and asked the state for a certificate of need. In an environment of greater government involvement in health insurance and rate setting, state officials had to approve any new health facility.

“We thought we had it locked up,” recalled Vic Broccolino, then the chief financial officer at Bon Secours Hospital, later its president and then president of Howard County General for 23 years.

Like most Catholic hospitals, the sisters refused to provide abortions. What’s more, they refused to even refer women to another facility for abortions, Broccolino said. State officials refused to issue their certificate of need.

State officials did grant approval to Lutheran, however.

As this was happening, the Columbia Hospital and Clinics Foundation had opened its 59-bed facility at Cedar Lane and Little Patuxent Parkway in July 1973. But hospital leaders were also contemplating its future. Ron Carlson, who would serve 11 years on the hospital board, recalled Hal Cohen, longtime head of Maryland’s Health Services Cost Review Commission, saying, “If there is a second hospital, your financing will not allow you to survive.”

Two warring camps developed, one led by Miller favoring the second hospital, and the other the Citizens Committee for Sensible Hospital Planning, a group opposing Lutheran’s plan. This was one of the first steps in political involvement by Liz Bobo, later to serve as a Howard County Council member, county executive and state delegate, and Angie Beltram, later elected to the county council herself. The battles were fought in the newspapers and mind-numbing hearings at state agencies and local boards.

The Columbia Hospital board decided to transform itself into a community hospital with a community board. After some internal debate, it dropped Columbia from its name, and in 1974, the facility became Howard County General Hospital.

The following year, the county council, elected with the strong support of Columbia residents, passed a rezoning law that prohibited a hospital from being built on Charlie Miller’s Grey Rock farm. Over the strong objections of Lutheran Hospital officials, who called it “very, very unjust,” in June, the state health systems agency refused to recertify its certificate of need for a second Howard County hospital.

In 1978, the state approved a 120-bed expansion to Howard County General. The need was evident since the hospital had been leasing two floors of the Lorien Nursing Home, down Cedar Lane, for patients.

The limitations of a 59-bed hospital were painfully clear in October 1979 when Sarah Lazarick came into the world after a long and difficult labor. As she arrived, three weeks late, the Apgar score for her physical condition was 2 out of 10, then 4 out of 10. She was being worked on intensely across the delivery room, and since the small Columbia hospital had no neonatal intensive care unit, the infant with a full head of dark hair was taken by ambulance to Saint Agnes’s newborn ICU. Even though she had aspirated amniotic fluid, she looked a lot better than some of the other babies, many of them preemies. The first chance I got to hold my baby daughter, conceived and born in Columbia, was in Baltimore.

Broccolino Arrives

Howard County General Hospital President Vic Broccolino, right, at his retirement in 2013 with Ronald Peterson, president of the Johns Hopkins Health System. Photo by Caruso Studio, courtesy of Columbia Archives.

No evidence of the small, conflicted beginnings of Howard County General Hospital remains on the massive campus it has become, surrounded by professional office buildings for medical practices. HCGH now has 264 beds, a budget of more than $235 million, and it needs a parking garage for its 1,900 full- and part-time employees. In the past year, it served more than 220,000 people, as patients, outpatients and emergency room patrons. Almost 3,600 babies were born in the last fiscal year — more than 100,000 since it opened in 1973 — and any seriously ill babies can be cared for in the Lundy Family NICU since 1990.

That’s the year Vic Broccolino became president, becoming the public face of the hospital for 23 years. “I was blessed that I got the job,” Broccolino said in a recent interview. “The patients in Howard County were so different than we saw in Bon Secours,” where he had been serving as president.

“The biggest challenge providing health care out here is the expectations of the people,” Broccolino said. The residents know what they should be getting from their health care providers.

He said the hospital board gave him three tasks: “Improve our visibility in the community; make peace with the medical staff; and make some money.”

It turns out that despite the highest occupancy rate for a Maryland hospital and a well-insured community, HCGH in its 17 years had barely turned a profit and “the debt service was huge,” with the highest debt ratio for a hospital in the state. “Every project was financed,” Broccolino said.

He also discovered lingering hostility from the two-hospital fight in the 1970s. People in western Howard County told him: “We will never use your hospital.” That included a top business executive he eventually recruited to the board. Broccolino told the man: “If you have a heart attack, the ambulance is going to take you here.”

He also found that the administrators lacked engagement with community organizations, and insisted that “everybody in the administration had to serve on two boards.”

Sold to Hopkins

By 1995, the nonprofit hospital had shown a net profit of $3.5 million, and its facilities and services continued to grow. In 1996, it was clear that with the wave of mergers and acquisitions that was sweeping the country among both nonprofit and for-profit hospitals, “we were going to get sucked up” into a bigger system at some point, Broccolino said. The board decided: “Now is the time to make our move.”

The hospital hired Morgan Stanley’s unit on health care mergers and acquisitions as a consultant and sent an RFP to 22 hospital corporations. It received 16 responses to the HCGH’s request for proposals — “they had to do a lot of work” to respond, Broccolino said. Over the course of time, a nine-member hospital board committee narrowed it down to three choices: Johns Hopkins, Saint Agnes and Universal, a Pennsylvania for-profit.

The board committee wrangled over the options, and finally Broccolino asked the question: “Which of these institutions will be around in 50 years?”

The Johns Hopkins Health System, whose predecessor had played a key role in starting the hospital, was the obvious choice.

None of this internal process had been made public. When the announcement of the Hopkins purchase was made, many people in Columbia and Howard County were upset at being kept in the dark, including an editorial writer at the Columbia Flier. As past or future patients, they felt they had been sold without their permission.

The hospital board chairman at the time, Al Scavo, of the Rouse Co., conceded, “It’s emotional, it’s traumatic, and it deals with change.”

In the deal, Johns Hopkins “paid” $142 million, taking on all the hospital’s debt. More than half of that, $73 million, would be used to endow a community health foundation to fund and promote health initiatives exclusively in Howard County.

As Broccolino explains, it was really a leveraged buyout. Hopkins in essence took a mortgage out on the hospital’s assets and promised to pay off the debt — with the revenues from Howard County General. Hopkins was on the hook, but the money would actually be repaid by the patients.

Howard County General Hospital today. Photo by Len Lazarick.

Healthy County

People in Columbia and Howard County start out with advantages. That was obvious to Dr. Peter Beilenson when County Executive Ken Ulman recruited him in 2007 to be the county health officer after 13 years as health commissioner in Baltimore, a city beset with violence, teen pregnancy, lead poisoning, drug addiction and poor primary care.

His offices were just 12 miles apart, but “I went from the fifth poorest [jurisdiction] to the third wealthiest county” in the country, Beilenson said in an interview. “You had to find things to work on in public health” in Howard County.

Beilenson describes a “four-legged stool for a healthy community.”

- Safe, affordable housing;

- Access to health care and healthy foods;

- A decent public school system that prepares students for today’s economy;

- Access to livable wage jobs.

By all these measures, Howard County is “vastly healthier” than Baltimore and many other areas. “The zip code you grow up in affects the outcomes you have in your whole life,” said Beilenson.

Giving access to health care to the uninsured became a major goal, leading Ulman and Beilenson to set up the Healthy Howard program. Beilenson says it reached “probably half the uninsured,” households making $75,000 or less. That was eventually preempted by the Affordable Care Act, and “I was bored silly,” so he turned to developing Evergreen Health, a new nonprofit model under the ACA.

Besides the strong four legs of a healthy community, Beilenson noted that Howard also has a strong network of nonprofit organizations through the Association of Community Services. Scores of groups provide a network of support beyond the traditional health care providers. In Howard County, “People were very collaborative” in solving problems, he said, much more so than in Baltimore.

Over the years, an array of alternative health organizations emphasizing holistic and nontraditional approaches to health and wellness have blossomed here, as well. One of those is the Maryland University of Integrative Health, now located in Maple Lawn, which was founded in Columbia in 1974 as the College of Chinese Acupuncture, and renamed the Tai Sophia Institute in 2000. It now offers fully accredited graduate degrees in acupuncture, oriental medicine, holistic health and herbal studies.

The Horizon Foundation

Broccolino said the $73 million paid by Johns Hopkins that endowed what became the Horizon Foundation was the “biggest payoff” Morgan Stanley had seen to that point.

Looking at what Horizon does to promote community wellness points out how backward a narrative on health can become when it emphasizes only hospitals, physicians and health insurance. That story line tends to emphasize what happens when people get sick, as opposed to stressing how they can stay well — a gap the original Columbia Medical Plan tried to bridge.

As head of the Horizon Foundation, which is the only independent health foundation in Maryland, Nikki Highsmith Vernick dissents from Beilenson on some points. “I find there’s plenty of work to do in Howard County,” Highsmith Vernick said in an interview. “Our public health status is no different than anyone else. … We have significant disparities in health.”

Highsmith Vernick is only the second director of the foundation that was headed for its first 14 years by Richard Krieg and now holds about $85 million in assets. Through 2015, it awarded more than $40 million in grants to a broad array of community organizations and initiatives. Among those were grants that helped set up the Columbia Center of Chase Brexton Health Services, Howard County’s first federally qualified health center where low-income and uninsured residents can find comprehensive care — in a building once occupied by the Columbia Medical Plan.

When Highsmith Vernick arrived at Horizon in 2012, the board developed a new strategic plan that focused on promoting positive lifestyles and increasing access to high quality health care. The foundation has continued grant-making to Howard County organizations and agencies, but it has decided to concentrate on several main initiatives, while weaning some organizations from its support.

One of Horizon’s key goals is reducing obesity, with a particular emphasis on curtailing consumption of soda and sweetened drinks. Why obesity? When you look at the county’s health statistics, Highsmith Vernick said, “everything is green, and that one is red.” In the last four years, Howard County’s consumption of sugared beverages has declined by 20%, she said. “That’s two or three times” the rate of decline in the U.S. as a whole.

Another focus is behavioral health, which is always underfunded. “We don’t have as many community mental health centers as we should,” Highsmith Vernick said. “Most of our psychologists and psychiatrists do not take insurance.”

That’s why Horizon partnered with the Howard County Mental Health Authority and Way Station, a nonprofit agency, to aid residents experiencing mental health crises, regardless of income.

Horizon also wants to increase the availability of sports programs to all children. “I worry that we’ve created a pay-to-play system” of private youth sports leagues, said Highsmith Vernick. She would like to see more after-school sports offered as well as sports programs in middle schools.

Horizon has also established an initiative to tackle one of my pet peeves about Columbia since I began covering business here: its lack of walkability (and bikeability too), an absence particularly obvious in Columbia’s office and industrial parks. “You can’t walk there from here” could be said about many places in Columbia, despite 94 miles of pathways, largely through woods and open space areas. Horizon calls its program Open Streets, and wants the county to invest $3 million in safe bikeways along county roads.

Overall, Highsmith Vernick doesn’t disagree that Columbia and the county are already a very healthy place.

“We have built a pretty amazing health care system in Howard County,” she said. “We have all these amazing institutions of health.”

Next Month: Part 8: Religion

Len Lazarick

Len Lazarick ([email protected] ) has lived and worked in Columbia as a journalist for more than 40 years. He is currently the editor and publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government and politics, and a political columnist for The Business Monthly.

Part 1: How the ‘garden for growing people’ got planted and grew

In this first installment, Len Lazarick looks at how a new town with ambitions to be a real city “not just a better suburb” came to be on 14,000 acres of Howard County farmland with lofty goals that faced some hard realities.

Part 2: Working in Columbia: Its Downtown and Business Parks Went Up and Down With The Economy

Part 2 focuses on the businesses of Columbia as an essential part of the plan.

Part 3: Shopping and Retailing at the Heart of the Columbia Plan

Part 3 examines the central role of shopping and retailing for the development of the Columbia plan. With changes in both lifestyles and retailing — and a couple of poor locations — the village centers did not always work out as planned.

Part 4: Media in the New Town: Communications part of building community; the Flier and the rest

Part 4 examines the role of media in creating the community, primarily newspapers, and in particular, the Columbia Flier.

Part 5: POLITICS: The Shifting Weight of Columbia Power

This is the fifth part in a series of 12 monthly essays over the next year leading up to Columbia’s 50th birthday celebration next June. This month looks at the shifting dynamics of political power in Howard County because of the presence of Columbia and its largely Democratic voters.

Part 6 EDUCATION: Schools Were Crucial Then and Now

Part 6 examines the planning and transformation of a small, rural, recently desegregated school system with middling rankings to one of the best school systems in the country. Howard County now has 76 schools with 54,000 children and 4,100 teachers, and they face the challenges of diversity, particularly in its urban core of Columbia.

Part 7: HEALTH CARE: Planning for a healthy community — an innovative HMO, a hospital fight and the quest for wellness

Health care was another key element the original Columbia planners focused on in their 1964 work sessions. Unlike the schools, land use, water, sewer and political structure, for which the Rouse Co. planners eventually would turn to government institutions that already existed in Howard County, they would need to look beyond its borders for help. The opening of the Columbia Hospital and Clinics in 1973, would be one of the most controversial aspects of Columbia’s early years. Its creation was fraught with community tension, political discord and hostility among competing groups, creating ill-will outside of Columbia that would last for decades.

Part 8: RELIGION: Interfaith centers sought to bring congregations together

These interfaith centers in Wilde Lake and Oakland Mills, the first religious facilities built in the planned new town, were among the unique features most often remarked on with wonder in media coverage of Columbia. While they were consistent with the open, integrated and forward-thinking city Jim Rouse had in mind, they were not part of the original planning process at all.

Part 9 ENVIRONMENT: Respecting the Land While Building a City

“To respect the land” was one of the four basic goals for Columbia often repeated by developer James Rouse more than 50 years ago as he pitched his proposal “to build a complete city” on 14,000 acres of farmland, woods and stream valleys. The goals seem almost a contradiction. If he wanted to “respect the land,” why not just leave the fields and forest as they were? Because they were not going to stay that way for long as suburban development spread from Baltimore and Washington along the new interstate highways.

Part 10: ARTS at the Heart of the New Town

The Merriweather Post Pavilion was one of the first structures built before Columbia even had its first residents. Now it is being redeveloped and is at the center of the Merriweather District that is the core of Columbia’s new downtown. But Merriweather is only part of the arts scene in the planned community.

Part 11: Recreation and the Role of the Columbia Association

Keeping a sports facility open that runs consistently at a big loss may seem like a poor financial decision. Yet it is completely consistent with the original philosophy behind the Columbia Association. As Columbia got started, every one of the amenities and facilities ran at a loss, not to mention the debt it took to build them. As Columbia looks to the future, CA not only wants to keep the pools and athletic facilities open, but to keep Jim Rouse’s vision alive.

Part 12 Conclusion: A 50-year-old town faces its future

Veteran journalist and longtime resident Len Lazarick wraps up by looking back over the past 50 years and looking forward to Columbia’s future. All 12 chapters have now been published as a 200-page book.

Recent Comments