By Len Lazarick

The just-started Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education has been described as largely about rejiggering school funding in Maryland.

“Our charge is much, much broader than money,” commission chair Brit Kirwan told the members Monday. “Equally important is how we spend the money.”

“What are the successful innovations that can make our schools better,” said Kirwan, the former university system chancellor. “We all have the same goal. We want Maryland to have the best schools for our children.”

That’s what two dozen commission members explored with the aid of three national education experts who took a broad view of how public schools should be improved — the sooner the better.

The commission is scheduled to start dealing with money issues at its Dec. 8 meeting, when it hears from consultants who have been studying adequacy of funding. As expected, their draft recommendations call for more funding.

But Marc Tucker of the National Center on Education and the Economy made clear that more funding for schools is not the solution for better schools without fundamental changes in structure.

Lots of spending, little improvement

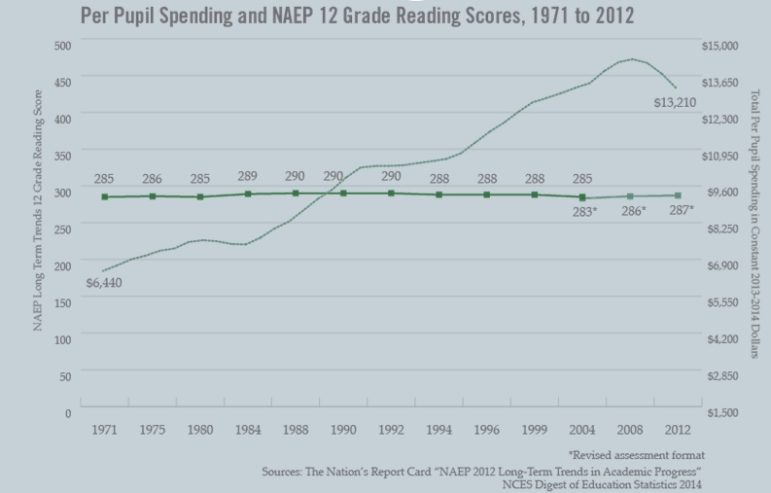

He made the point with a simple chart mapping the increase in per pupil spending in the United States for 41 years versus the scores for the national 12th grade reading test. From 1971 to 2012, average per pupil spending in the U.S., adjusted for inflation, more than doubled, rising from $6,440 to $13,210. The scores on the reading test were flat.

“It’s dead flat,” Tucker said. “If you can’t read, you can’t do math. If you can’t read, you can’t do science. If you can’t read, you can’t do history. If you can’t read, the rest of the game is over.”

Tucker and his center has been researching the best performing education systems around the globe for 28 years. He’s found that many countries produce better results with far less money than is spent on education in the U.S., often using concepts first developed here but not widely implemented.

Because there has been a “vast extinction of low-skill, low-wage routine work in high wage countries,” Tucker said, in the U.S., “we’re educating half our kids for a world that will provide them no employment.”

Here is the full PowerPoint of Tucker’s presentation entitled “What it will take for Maryland to compete with the best education systems in the world.”

“These other countries that used to be behind us are now way ahead,” said Tucker.

In response to a question from Craig Rice, a Montgomery County Council member, about whether the foreign school systems studied had the same issues with diversity, Tucker said some of the systems, such as Shanghai, had large numbers of disadvantaged students speaking other dialects.

Nine building blocks

Tucker offered nine building blocks of an education reform agenda, but he emphasized that they all needed to work together as a system, and were not a “silver bullet” in themselves that would create better performing schools.

- Strong supports for children and their families. This includes comprehensive supports for families with young children, from family allowances to prenatal care to nutritional assistance and more affordable day care, preschools and early childhood education.

- More resources for students who are harder to educate: The United States is the only advanced country in which children of the wealthy get more financial support than children of the poor, Tucker said. They also need more teachers per student and, in some cases, the best teachers, in schools serving disadvantaged students.

- World-class, highly coherent instructional systems with internationally benchmarked student performance standards and matching curriculum frameworks.

- Qualification systems with multiple no-dead-end pathways for students to achieve those qualifications. No high school diploma (a certificate of attendance, Tucker said) but requirements at the end of each education stage match the requirements for beginning the next stage. No dead ends, many opportunities to change direction and combine qualifications

- Abundant supply of highly qualified teachers. Recruit most teachers from upper segment of high school graduates (top half to top 5%). Move teacher education into research universities with entrance requirements those of selective universities and give them tough content with research requirements. Have elementary teachers specialize in fields, such as math and language.

- Schools organized and managed to attract high quality candidates into teaching and to enable them to do their very best work. There should be a career ladder for teachers and school leaders combined with strong incentives for teachers to get better and better at the work. More time should be spent working together in teams to improve school performance, less teaching. Tucker said compensation should not be based on degrees and seniority, as it is now.

- An effective system of career and technical education and training, built on very high level of student academic performance. It should have highly qualified instructors, modern equipment, and a strong apprentice component; a training wage; Strong employer involvement.

- Leadership development system that develops leaders who can manage such systems effectively. This is a recent development, and most systems are catching up on this, Tucker said. Only those who have been fine teachers, team leaders and mentors can go on to leadership positions and they must have experience in low-income and minority schools to move up.

- Coherent governance system capable of implementing effective systems. Built on professional model. The system sets the rules, provide resources, but professionals have professional discretion, and accountability runs up and down

Tucker emphasized that many of these nine developments take 20 or 30 years to implement in other countries and require a long-term commitment to systemic change.

No time to lose for a little castor oil

Tucker’s presentation was reinforced by Lee Posey of the National Conference of State Legislatures which produced a report in August called “No Time to Lose,” embracing many of the features of Tucker’s building blocks. Tucker was a consultant to NCSL’s study group which included legislators of both parties from around the country, as well as legislative staff. The study group included Sen. Rich Madaleno, D-Montgomery, who is on the Maryland commission and Rachel Hise of the Department of Legislative Services, who is staffing the commission.

“It’s not just about money,” Madaleno told the commission. “It is about structure — not just about how we fund education in Maryland.”

“It all works together,” said Posey.

David Driscoll, former education commissioner of Massachusetts, described his reform efforts there which have produced some of the best test scores in the country. In the Education Week report card, Massachusetts and Maryland were usually in contention for the best schools in the country. Massachusetts students usually had better test scores.

“We’re the best of a poor lot,” said Driscoll. He emphasized the need for higher standards for education, and the importance of all the stakeholders in the schools to work together.

“Everyone is going to have to drink a little castor oil,” Driscoll said.

If you want to have the best schools and education then get rid of Common Core and Assessments, like PARCC. Keeping these, just shows you choose money over education and what is best for our kids.

The job of educators is to instill in students a fundamental drive to

learn how to learn such that math, science, and language skills more logically fall into place. I don’t see that covered in the discussions. Studying competitors’ more socialistic systems seems like a mostly-futile diversion without controlling for countless differences such as political and societal. Europeans have parliaments, we are a democratic republic. A blank slate is inherently the best starting point. Debating costs without interim consensus about scope and structure of reform is illogical.