By Josh Magness

Capital News Service

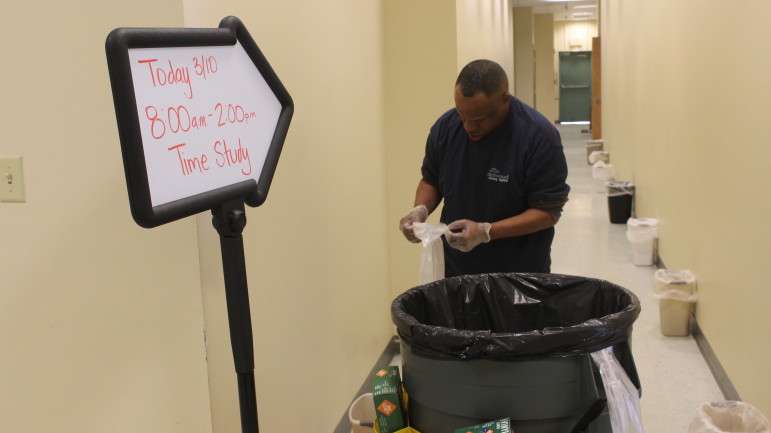

Brian Beckham, a custodial worker with disabilities at Melwood, finishes tying up the final trash bag during a demonstration of the now-obsolete time trials in the Melwood center. Capital News Service photo by Josh Magness.

During Mat Rice’s time as a student at the Maryland School for the Blind, the disability advocate said he would work at a place openly referred to as “the workshop.”

Rice, who has spastic cerebral palsy and is legally blind, said he would crush cans and shred paper when in the workshop. Each day, he said, he received a piece rate wage based on the amount of cans and paper he would get through, earning about 10 cents a piece and “definitely” falling below federal minimum wage of of $7.25 an hour.

At first, Rice thought the practice was confined solely to the school. But once Rice started working with disability rights groups, he said, he soon learned it was legal for many institutions to pay their workers with disabilities a subminimum wage.

But the Minimum Wage and Community Integration Act, HB420/SB417— a pair of bills that passed both the Maryland House and Senate with wide, bipartisan majorities — aims to end that practice.

3,600 workers affected

As of January, 36 in-state organizations were authorized to pay just over 3,600 workers with disabilities less than the minimum wage, according to a legislative analysis.

The legislation does away with 14(c) certificates, which enable certain employers and work activities centers to pay their employees with disabilities based on productivity instead of at a fixed rate. The two bills also require a worker with disabilities who is paid a subminimum wage and a supervisor to outline a plan to get a job with non-disabled coworkers.

Ending the confinement of workers with disabilities to their own workplaces is one reason why the legislation is so important, Rice said.

But the most pressing issue is ensuring that employers can no longer pay their workers with disabilities a subminimum wage, which constitutes a civil rights violation, said Rice, a public policy specialist for People on the Go, an advocacy group for Marylanders with physical and mental disabilities.

“We have a practice here that singles out people with disabilities,” Rice said, “and says that because you are judged to be less than productive, then we can pay you less than any other group of people within the state.”

The legislation tapers off the ability for employers to receive permission to pay less than the minimum wage to workers with disabilities, but allows companies that received a 14(c) certificate before the Oct. 1, 2016, deadline to continue paying subminimum wages under certain circumstances for four years.

Can continue till 2020

By Oct. 1, 2017, the Developmental Disabilities Administration and the Department of Disabilities must submit a plan to the governor and the General Assembly outlining the transition away from subminimum wages, which becomes final on Oct. 1, 2020.

Starting Oct. 1, 2016, the Maryland Commissioner of Labor and Industry may not authorize additional work centers to pay their workers a subminimum wage.

But if a work center held a 14(c) certificate before the Oct. 1 2016 deadline, they can continue paying their workers with disabilities below the minimum wage until October 2020 as long as they notify the employee of other job opportunities and have a plan for healthcare services that help with daily functioning.

The bills also allow those centers that have a certificate granted before 2016 to continue paying their workers below the “prevailing wage” — or the pay given to a majority of workers in a certain field — after the 2020 deadline, as long as they keep the certification.

Wages based on time trials

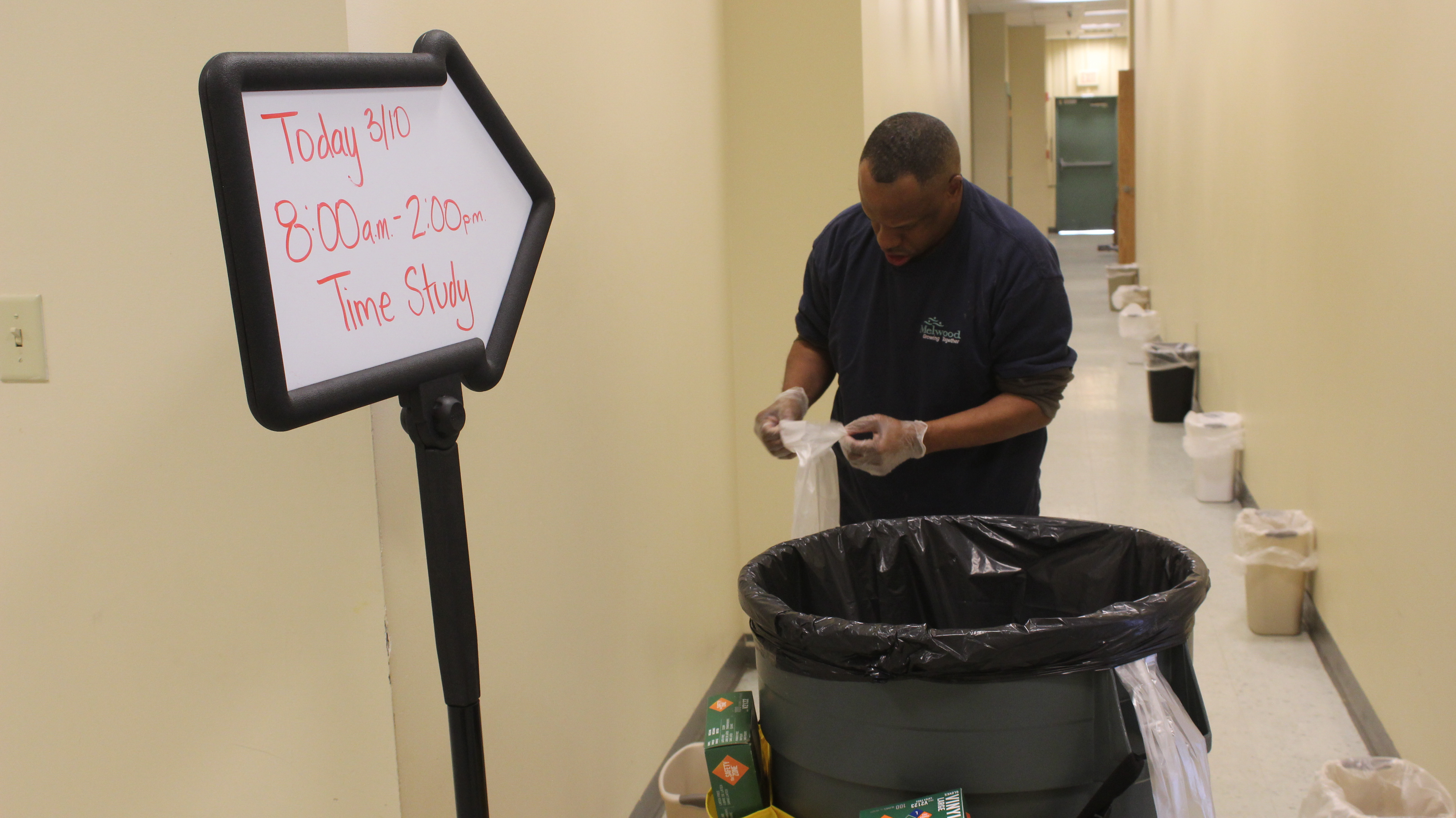

Carla Walker, the time trial administrator at Melwood, watches Brian Beckham as he signs a form stating that the mock time trial, conducted to demonstrate what the process used to entail, was administered fairly. Capital News Service photo by Josh Magness.

To determine an employee’s specific wage, employers conduct a “time trial.”

Melwood, a work activity center that employs those with disabilities in mostly custodial and landscaping jobs, stopped performing those tests this February. But before that, Carla Walker, the time studies administrator for the center, conducted roughly 800 of the trials every year.

Walker would begin the trials by using a stopwatch to record how long it takes three non-disabled people to complete a set of tasks and calculating the combined average time. Then she would time how long it takes a worker with disabilities to complete the same task, which is based off of the job they wish to have.

The worker’s wage was then set proportionally by comparing the time it took them to complete the task against the combined average of the three non-disabled workers.

Nancy Pineles, a managing attorney for the Maryland Disability Law Center, said that process is inherently unfair to those with disabilities.

“Each of us who don’t have disabilities, we are not measured based on our productivity, but our productivity varies pretty widely among our peers,” Pineles said. “Only people with disabilities are studied in this way, and some are paid as little as eight cents an hour. How does that work?”

Melwood gave raises in March

In March, one month after Melwood did away with the trials, the work center sent out the first paycheck that gives all workers a rate that is at or above the minimum wage. That translated into a pay raise for around 400 of the over 900 employees with disabilities that Melwood oversees, said Cari DeSantis, the work center’s president and CEO.

Before Melwood ceased the time trials, DeSantis said, some workers with disabilities filed complaints to the Federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which enforces federal employment discrimination laws. She said those questions put Melwood in an awkward position of defending the practice as legal while understanding the workers’ legitimate concerns.

“Our mission calls us to envision a world where people with differing disabilities are fully included,” DeSantis said. “So how can people with differing disabilities be included if they aren’t given the opportunity to have wages like the rest of us?”

Funding raises costs

But DeSantis concedes that funding the switch to higher wages was also a concern.

“We struggled to make it work because it has a financial impact, but it’s the right thing to do,” she said. “It will now become important for us to do fundraising and tighten our operational spending so we can keep up that vocational support.”

Chimes International, an organization that provides educational and job services for workers with disabilities, was originally opposed to the legislation. But amendments, including one that mandated a supplemental work plan to aid workers with disabilities in community integration, assuaged their concerns.

“Chimes’ concerns (sic) … was that individuals with disabilities not be harmed,” Marty Lampner, chief executive officer of Chimes International, wrote in an email. “Chimes concerns are being addressed (through amendments) and as an organization we will continue to work with concerned legislators” as the bill becomes implemented and moves forward.

Kenneth Simon, a custodial worker at Melwood, didn’t necessarily dislike the time trials. They allowed him to increase his speed at certain tasks, he said, but they also made him afraid of “being at the bottom” of the pay rate compared to his coworkers.

“I felt scared,” Simon said. “I didn’t know how well I was gonna do. I like to clean and I didn’t want to do my job for nothing.”

Compared to civil rights movement

Rice said he understands the concerns of some opponents to the legislation, who are wary that employers will be hesitant to hire workers with disabilities, potentially leaving some without jobs. But he also points to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, when some were concerned about working with black Americans, as a parallel of the current issue.

“People with disabilities are unfortunately facing a similar level of opposition when it comes to employment,” Rice said. “But we should not fear change; we should embrace change.

The bill is on the desk of Gov. Larry Hogan. The bill is under review and there is not yet a timeline for signing it, a spokeswoman said Thursday.

So, why should an employer hire someone who can do half the job at the same price as someone who can do the whole job?