By Dan Menefee

The Kent Guardian for MarylandReporter.com

The Clean Chesapeake Coalition, a group of seven Maryland counties formed in 2012 to challenge the priorities and science of the $14.4 billion cleanup mandate for the Bay, is again sparring with environmental groups it says continue to ignore the Susquehanna River as the single largest source of pollution that flows into the Bay.

In 2013 and 2014, the coalition challenged the “futility” of spending $3.7 billion over a decade to reduce 50,000 pounds of nitrogen from septic systems — while no dollars were appropriated to deal with pollution from the Susquehanna River. The Susquehanna jettisons 131 million pounds of nitrogen through the floodgates of the Conowingo Dam annually, nearly 50 percent of the total nitrogen load into the Bay.

Septic systems by contrast account for just seven percent of Maryland’s nitrogen discharge into the Bay.

Argument moves to phosphorus

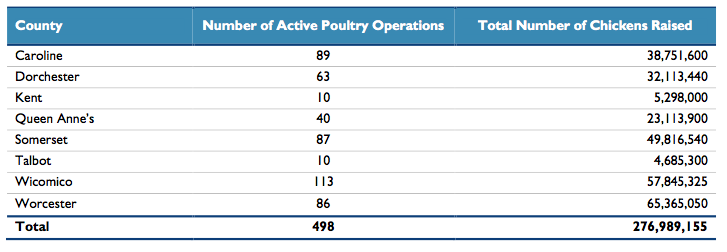

This year the argument has moved to phosphorus. Environmental groups have taken aim at the Eastern Shore’s chicken belt, floating an idea for an eight-year moratorium on new chicken houses until a Phosphorus Management Tool is fully implemented in 2024.

The PMT is a regulatory regime that was agreed to by the administration of Gov. Larry Hogan to limit the amount of chicken manure spread on farms. The PMT will measure how much phosphorus is already present in the soil. If saturation reaches certain levels, farmers must scale back or eliminate the use of chicken manure to stay within legal limits.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Midshore Riverkeeper Conservancy, Waterkeepers Chesapeake and the Environmental Integrity Project are among the environmental groups advocating the moratorium on chicken houses to answer cuts to the number of water quality monitoring stations from 16 to 9 in 2013. The state cited EPA budget cuts for reducing monitoring sites.

“Reduced monitoring will make it much harder to determine whether the state’s new efforts to limit runoff pollution with the Phosphorus Management Tool are working or need to be strengthened,” said a Sept. 8 report from Environmental Integrity Project called More Phosphorus, Less Monitoring. “Agriculture accounts for 55 percent of the phosphorus pollution that stimulates algal blooms and robs the Bay of the oxygen needed to support aquatic life, and poultry litter accounts for most of the phosphorus runoff on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.”

Farm sources vs. the dam

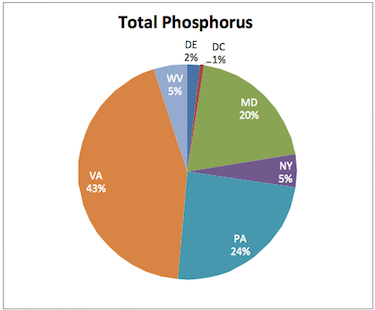

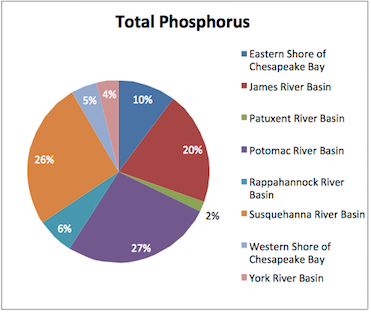

All of Maryland contributes 20% of the total load of phosphorus annually into the Bay, of which half (10%) comes from the Eastern Shore. Below Source, EPA

The Conowingo Dam releases 30 percent of the total annual phosphorus into the Bay, and this flow originates in Pennsylvania and New York. This does not include phosphorus released during storm events.

Kent County Commissioner Ron Fithian, who chairs the Clean Chesapeake Coalition, fired back at the report, saying phosphorus from Eastern Shore agriculture pales in comparison to what surges through Conowingo Dam annually.

“Maryland’s annual average phosphorus loading to the Bay from agriculture is 985 tons (1,970,000 lbs.). Meanwhile, the average annual phosphorus loading from the Susquehanna River (the largest tributary feeding the Bay) is no less than 3,300 tons (6,600,000 lbs.), not including what is scoured from behind Conowingo Dam and the other reservoirs in the lower Susquehanna River during storm events,” Fithian wrote in a Sept. 18 statement called, More Hysteria, Less Science. “The Susquehanna River dumps nearly 600% more phosphorus each year into the Bay than the phosphorus loading attributed to all Maryland agriculture.”

“Maryland’s annual average phosphorus loading to the Bay from agriculture is 985 tons (1,970,000 lbs.). Meanwhile, the average annual phosphorus loading from the Susquehanna River (the largest tributary feeding the Bay) is no less than 3,300 tons (6,600,000 lbs.), not including what is scoured from behind Conowingo Dam and the other reservoirs in the lower Susquehanna River during storm events,” Fithian wrote in a Sept. 18 statement called, More Hysteria, Less Science. “The Susquehanna River dumps nearly 600% more phosphorus each year into the Bay than the phosphorus loading attributed to all Maryland agriculture.”

The Eastern Shore’s contribution to phosphorus is roughly half of Maryland’s total, or 10 percent of the total phosphorus discharge into the Bay.

Fithian also challenged the notion that chicken farming was adversely affecting aquatic life in the counties where poultry farming is the most intense.

“Kent County has just 10 chicken operations and the crabs and oysters have all but vanished in the upper third of the Bay, north of the Bay Bridge,” Fithian said in a brief interview with Kent Guardian on Monday. “Yet the oyster and crab populations are doing very well where poultry operations are significantly more.” MORE BELOW CHART

Fithian said the oyster populations are back to nearly 500,000 bushels a year “in the very areas targeted for a moratorium on chicken houses…the seafood industry everywhere south of Choptank River has enjoyed one of the best years on record.”

“We are wasting time, money and the public’s attention focusing on marginal pollution sources, while common sense and the best science tell us to be looking upstream at the single largest source of concentrated sediments, nutrients and other contaminants threatening the Bay,” he said.

Background of the mandate

This satellite photo shows a plume of sil from 19 million tons of nutrient laden sediment spilled into the upper bay from Tropical Storm Lee, September 2011, four million tons was scoured from behind the Connowingo dam

The state cleanup mandate was the result of a lawsuit won by Chesapeake Bay Foundation in 2010 that legally bound the EPA to enforce the 1972 Clean Water Act.

Under a consent decree, states in the Chesapeake Watershed, from New York to Virginia, were required to adopt Water Implementation Plans that reduced the Total Maximum Daily Load of sediment, nitrogen and phosphorus into the Bay, and bring the Bay into compliance with Clean Water Act standards by 2025.

As a result, the Bay was put on a pollution diet that required local communities in Maryland to draft their own cleanup plans.

Maryland drafted its Water Implementation Plan (WIP) by requiring local governments to enact local WIPs based on the idea that local governments could best identify their sources of pollution. In handing down the decisions to local governments the state also handed down the costs, which came to $14.4 billion.

These exorbitant costs came at a time when the state was cutting highway maintenance funds to local governments and passing along part of the burden of teacher pensions to county governments.

With little in the EPA mandate to address the Conowingo Dam, the Clean Chesapeake Coalition (CCC) formed around the idea of a multi-state solution to dredge the dam and restore its storage capacity as the most cost effective measure to reduce nutrient and sediment pollution.

The CCC has spotlighted Tropical Storm Lee in 2011 as proof the Conowingo Dam needed a remedy.

The Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper said in 2013 that the equivalent of 2,000 aircraft carriers of sediment rests behind the dam. The CCC and many waterman north of the Bay Bridge have blamed sediment spills for smothering the oyster and crab beds in the upper third of the Bay.

Why don’t these environmentalists figure out a way to utilize chicken manure like composting it, if possible, or turning it into a fuel, etc.

They should be able to be innovative…

Putting a moratorium on the growth of chicken houses won’t solve the problem and will serve to drive food costs higher and higher…

But, they aren’t rational in their thinking…

What do you expect from rabid environmental groups that go around sniffing chicken butts to achieve their 15 minutes of fame?

Dan,

I’m not sure if you are reporting that the environmental Community is not doing enough to address the Conowingo issue or whether you are just reporting that the Clean Chesapeake Coalition says that the environmental community isn’t doing enough. If it the former, you need to check your facts. Numerous environmental organizations are involved in multiple legal proceedings focused on the relicensing of Conowingo. If it is the latter, your readers might be interested in why a group with the name Clean Chesapeake Coalition uses its public relations machinery to attack efforts to reduce pollution from industrial chicken production.

Bob Gallagher

Annapolis

What a fine idea. No new chicken houses in the state for 8 years. Why not 15 years? Why not no growth in a key Maryland industry forever? The latter approach will surely limit Bay pollution going forward. Gotta love the environmental community; they are never at a loss to identify no-growth solutions to our problems.