This is the second part of a series by the Capital News Service about how plea deals punished the innocent in a Baltimore police scandal. The investigation by Capital News Service and Injustice Watch was completed as part of a nationwide examination of plea bargaining. Part One can be found here.

By Angela Roberts, Lindsay Huth, Alex Mann, Tom Hart and James Whitlow

Capital News Service

Omar Burley was among the first 105 Baltimore defendants whose convictions were voided as of mid-April after eight officers were convicted for robbing people, planting guns and drugs on them and lying on arrest reports to cover up their crimes.

A CNS analysis of court data found that all but four of the vacated and dropped cases involved guilty pleas. Nearly all, including Burley, were black men. More than half pleaded guilty while awaiting trial in jail, often for months.

Not all defendants were innocent. Rather, the state can no longer maintain their guilt.

The analysis was based on a list of vacated cases that CNS obtained from the state’s attorney’s office, additional cases identified during court hearings and a court database maintained by the Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service. Most involved gun or drug charges. In addition to the voided convictions, charges had been dropped in at least 48 pending cases.

Captive audience

In Baltimore, the first stop for defendants after booking is Baltimore City District Court for a decision on whether they should be released or held pending trial. Some are released with a court date. Others are held unless they can post bail — insurance they will show up for trial. Those deemed too great a risk are held without bail.

Unlike most major cities, Baltimore police officers usually make the initial decision on whether and what to charge the people they arrest, not prosecutors — and in doing so wield tremendous influence over the bail decision.

Studies have found that those in custody are much more likely to plead guilty. For example, a large study in 2016 for the National Bureau of Economic Research found that 43 percent of detained defendants pleaded guilty compared to just 21 percent of those released. Those behind bars have a weaker bargaining position.

The CNS analysis of the voided convictions found that 97 percent of the defendants were held in custody after their arrest. At the time they pleaded guilty, 57 percent were still in jail. Thirty-two people had been held without bail. Twenty-five had not been able to make bail.

“Alarming data”

Douglas Colbert, a professor at the University of Maryland law school who works on bail reform issues, said the analysis “reveals alarming data…It’s almost like a reversal of what should be taking place.”

Last year, a new state court rule required judges to set bail so it is more affordable for low-income defendants, and to release them without bail if they are not a risk. The early results show a drop in people held on bail but a rise in those held without bail.

A court officer called a commissioner makes the initial decision on whether to hold or release someone. Those held in custody then get a bail review hearing before a district court judge. The hearings are done remotely. Prisoners assemble at the jail in front of a camera that transmits to a television screen in the courtroom.

The judge is supposed to consider a variety of factors, such as employment, ties to the community and prior convictions. But the seriousness of charges and underlying facts weigh most heavily, Colbert said. CNS reporters found that defendants who try to challenge the police version of events during the bail review hearing often are told to save those arguments for trial — an opportunity most will not have.

“For the purposes of this hearing, many judges accept those allegations as true,” Colbert said. “In my opinion, they should not be doing that. Particularly now that we see that eight convicted officers repeatedly lied under oath when they presented charges to a commissioner or a judge.”

Barbara Baer Waxman, the Baltimore City District Court administrative judge, declined to be interviewed for this article as did Charles J. Peters, judge-in-charge of the criminal division of Baltimore City Circuit Court.

Held without bail

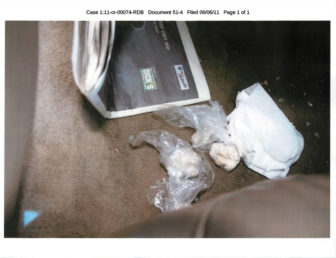

Sgt. Wayne Jenkins later admitted to arranging for 30 grams of heroin to be planted in Omar Burley’s car after the deadly collision. By the time of Jenkins’ confession, Burley had spent more than seven years in prison. Photo from federal court records.

Burley crashed a black Acura in 2010 while fleeing gunmen who turned out to be police officers. He struck another car, killing an elderly man. Police claimed he had heroin in his car and had been parked at a drug dealing location when they showed their badges and he fled, but he said he did not know the men were police and had no drugs.

Burley and his cousin Brent Matthews, who was with him in the car, were held without bail on the heroin charge in April 2010, and prosecutors added a manslaughter charge against Burley for Elbert Davis’ death. Their cases were sent to the Baltimore City Circuit Court, which handles serious felonies.

In February 2011, the heroin case moved into federal court, where Christine Celeste, a Baltimore City assistant state’s attorney on special assignment to federal court, took over prosecution.

The maneuver puts greater pressure on defendants to plead guilty, said James Johnston, an assistant public defender who represented Burley in Baltimore City court. They face the possibility of longer prison terms — and less sympathetic jurors — in federal court if they lose at trial.

Johnston, who is president of the Maryland Criminal Defense Attorneys Association, said federal jurors are drawn from a larger area that includes suburban and rural areas “who are seen by defense lawyers and prosecutors as substantially more likely to convict than Baltimore City jurors.

“That’s particularly true when the case comes down to a credibility battle between a police officer and a defendant in a criminal case,” he said.

Matthews, who faced a potential 20-year prison term, pleaded guilty in exchange for a four-year sentence with credit for time served. He did not respond to requests for an interview.

The stakes were higher for Burley. If he didn’t plead guilty and lost at trial, he said, the government would press the judge to increase his sentence for reckless endangerment, increase it further for causing a death and increase it yet again because he had a prior drug conviction. Instead of 15 years for a guilty plea, he could get 30 years or more, plus a potential $1 million fine.

“The stakes were too high,” he said. “So I folded.”

Burley said he still hoped to go to trial on the manslaughter charge, which remained in state court. He wanted to put on an official record somewhere the truth of what happened, he said. But he said he was told that would jeopardize the federal plea deal. He pleaded guilty to both in exchange for a 15-year term on the drug charge and a concurrent 10-year sentence on manslaughter.

Celeste and Thomas Crowe, Burley’s federally appointed lawyer, declined to be interviewed.

“I knew I didn’t have no drugs, and I knew that I was running for my dear life. So I thought that should be known in court,” said Burley. “But it never seen the light of day.”

Omar Burley chases his granddaughters through Druid Hill Park in Baltimore. He said he wants to see them accomplish things he didn’t, like go to college. “Whatever they want to do, I’m gonna stand behind it 100 percent because it’s their life,” he said. Capital News Service Photo by Alex Mann.

“A rock and a hardship”

Burley and Matthews went to prison. Jenkins continued his crime spree.

Anthony Branch crossed paths with him in 2014. Branch, then 20, was hanging out in front of a friend’s house when officers piled out of an unmarked car, Jenkins among them. Branch said they ordered the group to sit down on a nearby curb.

After searches of Branch and his friends yielded nothing, the officers arrested Branch. He said he asked but the officers never gave him a reason. He learned at central booking he was being charged for illegal possession of a firearm that he says he had never seen. The police report was signed by Det. Evodio Hendrix, later convicted in the Gun Trace Task Force scandal.

Branch said the commissioner set his bail at $250,000. At his bail review hearing, neither he nor his public defender were given a chance to challenge the police version of events, he said. The judge ordered Branch held without bail.

Five months passed. As Christmas approached, an assistant state’s attorney offered him a deal: If he pleaded guilty, he could get four years’ probation and return to his family that day. If he went to trial, he risked the maximum penalty of five years’ incarceration.

Branch lives with his older sister and his grandmother, who has diabetes. He said he worried about the stress his detention caused them, and about the extra household chores they had to shoulder. “It affected them in a lot of ways,” he said.

He felt stuck “between a rock and a hardship,” Branch said. “Because it was like, am I going to just plead guilty to something I didn’t do to get back to my family, or should I just… take it to trial and risk losing everything?”

He said he told his lawyers that he didn’t commit the crime. They believed him, he said, but “they were like ‘Man, at the end of the day, even if you didn’t do what they said you’re doing, how could you prove that?’”

Branch had previous misdemeanor convictions for drug possession and gambling. What did a 20-year-old like him have against the police, he recalled thinking. And, if he took the deal, he would be home by Christmas.

“I pleaded guilty, so I could get back to my family.”

The conviction would come back to haunt him.

In May 2017, Branch was a passenger in a car that police pulled over. After they found drugs and a gun in the vehicle, they charged him with violating his probation and slapped him with a new charge. His previous gun conviction added time to his sentence. He spent another nine months in jail before being transferred to a halfway house in February. In April, the court voided his original case. He was scheduled to be released from the halfway house at the end of May.

Capital News Service reporters Bryan Gallion, Laura Spitalniak, Carolina Velloso and Maria Herd and editor Deborah Nelson also contributed to these articles.

Recent Comments