By STEPH QUINN

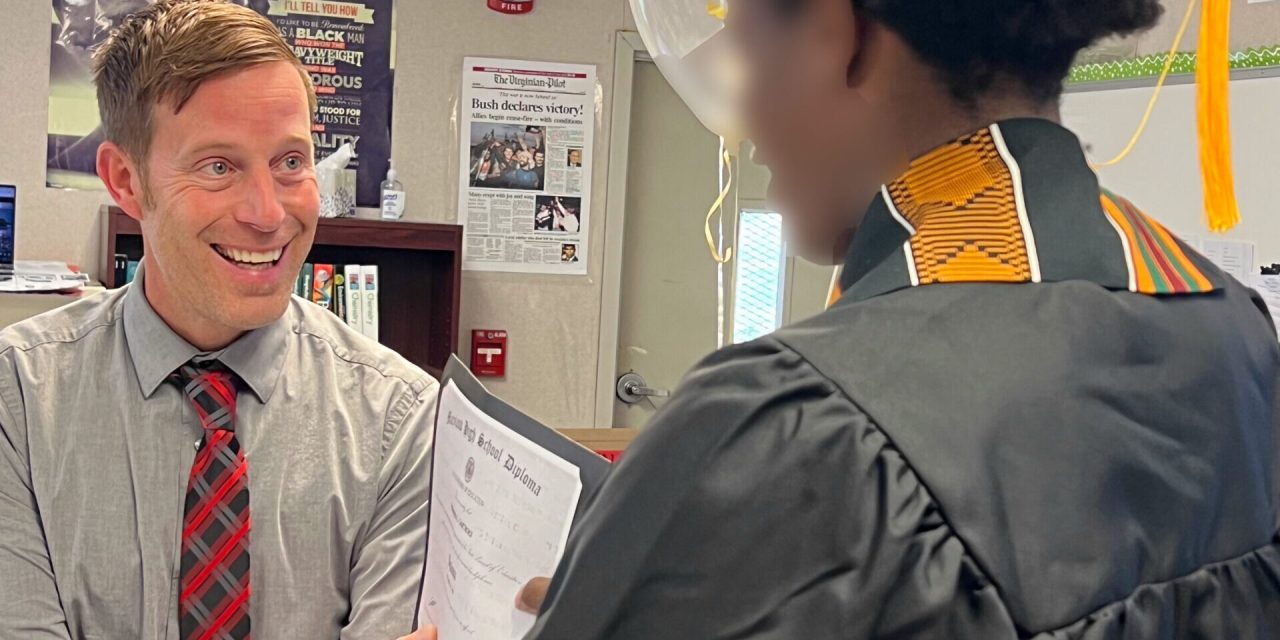

SABILLASVILLE, Md. — The graduate’s mom, peers and teachers knew he was going to reach his goal, though his principal, Todd Rasher, said the other students incarcerated at the Victor Cullen Center in rural northern Frederick County didn’t see “all the footwork” it took to earn his GED.

“This diploma ain’t really too much because I knew that I was going to get it,” the 17-year-old said to his graduation audience on Oct. 18, wearing a cap and gown, kente stole and black wristband adorned with, “Don’t give up.”

The graduate, whose identity CNS is shielding because he is a minor, was charged as an adult before his case was transferred to juvenile court. Rasher said he passed the tests necessary to earn his GED on the first try, inspiring his fellow students to take the tests themselves.

The graduate’s mom, TaNeya Anderson, said that services she and her son received since her son was locked up, including family therapy and regular updates from Cullen staff, have helped her family.

“It might seem like it was a bad thing that he ended up having to get incarcerated, but I’m always trying to get the good out of it, and I believe it was meant for this to happen this way,” Anderson said.

Not all incarcerated young people can continue their education, much less attain a degree. Two years after the Maryland General Assembly transferred responsibility for incarcerated students’ education from the state Education Department to an independent school board within the Juvenile Services Department, students confined in Maryland’s secure youth facilities continue to face multiple long-standing challenges, according to experts and state audit reports.

-

Teacher vacancy rates of 30% in the most populous Juvenile Services schools have led to reliance on streaming instruction in subjects such as math and science.

-

Incarcerated students were late to class hundreds of times in 2023 due to the security requirements — especially a state Juvenile Services policy mandating that staff supervise and escort youth while maintaining a minimum staff-to-youth ratio.

-

A lack of guidance from the State Board of Education has allowed local school boards broad scope to reject students charged with various offenses, including those who have been in detention, arguing they are a threat – even when Juvenile Services and the courts have decided it’s safe to release them.

Two of the state’s three most populous youth detention centers and its only long-term placement facility, Cullen, operated with teacher vacancy rates around 30% as of early October, according to documents discussed in public meetings of the Juvenile Services Education Program Board. The Baltimore City Juvenile Justice Center, which served 301 students that year, had eight vacancies. The Charles H. Hickey Jr. School, which served 245 students, had seven. Cullen, which served 76 students, had four.

When facilities lack subject experts to teach in person, students take classes livestreamed by juvenile services teachers from the Garrett Children’s Center, a former youth committed placement center in Garrett County.

Three of the nine Juvenile Services schools, including Hickey and Cullen, had no math teacher as of October, while four, including Hickey and the Baltimore center, lacked a science teacher. Baltimore’s Juvenile Justice Center was looking for a second math teacher to serve its large population.

David Domenici, director of education and senior adviser to the Juvenile Services secretary, said streaming instruction is “not ideal” for the “vast majority” of students but better than packets of photocopied activities.

Juvenile Services teacher vacancies have persisted through tensions between Maryland’s education and Juvenile Services agencies over the past decade about who bears responsibility for educating incarcerated young people and how best to do so. Those vacancies continue through teachers’ lack of summer and winter breaks and low pay relative to teachers employed by local school districts.

Lawmakers voted in 2004 to stage the Education Department’s takeover of Juvenile Services schools over eight years but repeatedly extended the timeline as Education protested inadequate funding. Bills seeking pay parity and summer breaks for juvenile services teachers failed in 2016, 2019 and 2020, often pitting experts from Education and Juvenile Services against each other. The General Assembly established a statewide education board within Juvenile Services in 2021 in response to monitors’ and advocacy groups’ repeated findings of high staff turnover and vacancies, inadequate services for learning-disabled students, and a lack of support for students returning to community schools. However, the law did not require pay parity or align facilities’ teaching calendar more closely with local schools.

Peter Leone, an emeritus University of Maryland education professor contracted by the Education Department to assess its work in Juvenile Services facilities between 2016 and 2018, said that educating incarcerated students was “a very low priority” for the Education Department.

The Education Department declined to comment on its management of Juvenile Services education or on the current board.

While public school teachers earn salaries set by local school boards, Juvenile Services teachers are paid on a single, statewide pay scale. Juvenile services teachers experience the greatest pay disparities in jurisdictions where local school boards pay the most.

The Juvenile Services board has implemented hiring and retention bonuses that board superintendent Kim Pogue said she hopes will improve recruitment.

Even with these bonuses, teachers in the state’s largest youth detention centers, in Baltimore and Prince George’s County, earn less per day than teachers working in local schools. A teacher at Hickey or Baltimore’s Juvenile Justice Center makes 9.5% less daily than a teacher in neighboring Baltimore County. A teacher at Cheltenham makes 3.9% less than a Prince George’s County teacher. In Washington County, teachers at the Western Maryland Children’s Center make 10.2% less than county teachers.

Domenici said the board would have to decide whether to seek legislative or other changes to teacher pay and work schedules. Domenici, who is not a board member, said the legislature should have set 10- and 12-month employee categories, established a school calendar limiting when Juvenile Services teachers can take leave, and creating a regional pay scale aligned with local districts.

But lost instructional time is greatest due to a lack of residential advisers, according to audits of Juvenile Services schools by the state Office of the Inspector General. Departmental policy requires that residential staff escort students from their living units to classrooms while maintaining a minimum staff-to-youth ratio. When there aren’t enough residential staff, students don’t move.

Students were late to class 203 times across Juvenile Services facilities due to residential staff shortages between April and June alone, according to the audits. Teachers had to teach class inside the living units 43 times in the 90-day inspection period.

Getting students in the classroom, even if they are late, Domenici said, is better than class on the living units. The department is working toward a goal of 90% on-time attendance in school by shifting all onsite adults to escort students to school, he said.

Spending time in detention or committed placement hurts students’ education in the longer term.

Legal experts and youth advocates say students who have been detained face obstacles returning to school due to overly broad state laws and an absence of guidance to local school systems from the Department of Education.

Law enforcement is required to report to superintendents and principals when students are charged with certain “reportable offenses” outside of school, including rape, first-degree assault and carjacking.

Experts say a 2022 state law limiting when local school systems can exclude students based on charges does not lay out a statewide standard to assess whether students present a threat nor outline procedures to protect students’ and parents’ rights.

Regulations that the State Board of Education has proposed to flesh out the law provide insufficient protections, according to comments submitted by the Public Defender’s Office, Disability Rights Maryland, and the Public Justice Center.

Alyssa Fieo, assistant public defender for education in the Juvenile Protection Division of the Maryland Public Defender’s Office, said she has worked on a handful of cases involving reportable offenses in at least five counties since the passage of the 2022 law.

Schools failed to hold required meetings between parents and school officials before students’ removal to establish whether students presented a threat, and schools don’t invite students’ attorneys when they do. In one case, the school system did not hold a required meeting to determine whether the alleged offense was a manifestation of a student’s disability before removing the student. In most of the cases, students were recently released from detention.

“A handful of the cases I’ve represented, the family got a phone call saying, ‘We understand your child has a charge. They’re going to be put on virtual school. We’re going to drop off the computer,’” Fieo said.

State law requires the state’s attorney to promptly notify school officials of the ruling on a student’s case, and the proposed regulations would require schools to then review the student’s school assignment. The three organizations are asking the Education Department to clarify that students should be allowed to return to school once the state’s attorney, Juvenile Services, and the courts have approved the student’s return to the community. There is currently no limit on how long a “reportable offense” charge can be used as a reason to exclude a student from regular instruction.

At Cullen, Rasher said, he has access to any student’s record, but he chooses not to look.

“I know everybody has a story,” he said. “Some are pretty awful. But to me, that’s not a thing.”

The day the graduate walked up to the podium and moved his tassel from one side of his cap to the other, he focused on his future: He was set to start work on an occupational safety certification the next day.

The graduate said Cullen’s walls enclose a complex reality that outsiders can’t see and that the youth of Cullen are just as complex.

“You can’t just judge a book by its cover like they say, for real,” he said. “If all of us in here, our cover is just what they show on the media or the news, you feel me, but they don’t know what actually goes on inside of here. …If you’re on the outside looking in, you’re not going to see what we see. Because we here.”

“I’m proud of what I did,” he said. “I’m definitely proud about it, but it’s more to come, so.”

Recent Comments