The mental agony of patients contemporarily due to COVID-19 is somewhat reminiscent of Wilkie Collins’ and Charles Dickens’ 1857 classic “The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices,” a poignant description of patients standing idly on the wards of an asylum: “Long groves of blighted men-and-women trees; interminable avenues of hopeless faces; numbers, without the slightest power of really combining for any earthly purpose; a society of human creatures who have nothing in common but that they have all lost the power of being humanly social with one another.”

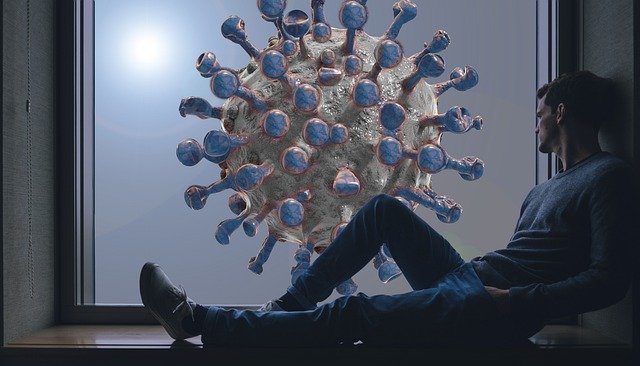

The outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic is impossible to predict, at the time of this writing. The statistics so far reveal an exponential growth in terms of people getting infected with the novel coronavirus and associated mortality, prompting the heads of states in the United States to issue stay-at-home orders or unprecedented lockdowns in other countries.

What we know about past pandemics is that the HIV/AIDS pandemic was associated with a global death toll of 36 million and the 2009 HIN1 influenza (flu) was associated with 151,700- 575,400 deaths worldwide during the first year it circulated. COVID-19 is still evolving and the top government scientists battling the coronavirus estimate that the deadly pathogen could kill 100,000-240,000 Americans, despite the disruptive social distancing measures that have closed schools, banned large gatherings, limited travel and forced people to stay in their homes — in essence bringing daily life to a grinding halt.

The first pandemic of the 21st century, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), caused a myriad of psychiatric problems, including depression, anxiety and suicide. The coronavirus pandemic appears to be following a similar pattern, if not worse. In addition to social distancing, which is causing us to be cut off from friends and family, the prospect of losing a job in a looming economic crisis as a pandemic threatens us and our loved ones, is making most of us ride an uncomfortable wave of emotions, primarily driven by uncertainty related to the future.

The ongoing public health crisis also is exerting a mental health toll on our health care workers, who comprise the best defense to contain and mitigate this pandemic. A recent survey-based study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, examining the mental health outcomes of 1,257 health care workers attending to COVID-19 patients in 34 hospitals in China indicates 50% experiencing symptoms of depression, 45% symptoms of anxiety, 34% having insomnia, and 71.5% experiencing psychological distress. With the U.S. now having more confirmed cases of coronavirus than any other country, coupled with a lack of safety and life-saving equipment, I foresee statistics in our health care workers either replicating China or being amplified.

During these precarious times, all of us need to be more vigilant about our mental health. The uncertain threat posed by this pestilent pathogen has evoked generalized feeling of angst among all of us. This is most likely stoking peoples’ anxiety and attributing to hoarding essential items and xenophobia.

We need to be cognizant of the fact that the world has endured several notable pandemics, including the Black Death, Spanish flu, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Apparently 80% of 2009 H1N1 pandemic-related deaths were in people younger than 65 years of age, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic caused 0.001 to 0.007% of global mortality, the 1968 H3N2 pandemic caused 0.03% of global mortality, and the 1918 H1N1 pandemic caused 1-3% of global mortality. Not too long ago, being HIV positive was analogous to having a terminal disease. Although still formidable, an AIDS diagnosis today doesn’t hold the power it once did.

Research has found that up to 70% of people experience positive psychological growth from difficult times, such as a deeper sense of self and purpose, a greater appreciation for life and loved ones, and an increased capacity for altruism, empathy, and desire to act for the greater good. A few days ago, a Minnesota state trooper pulled over a doctor for speeding and let her go with a warning. Apparently, the trooper handed the lead-footed cardiologist five N95 masks instead of a ticket from the supply the state had given him for his protection.

At this juncture, it is imperative that we take adequate care of ourselves because that is the only aspect of life over which we have control. In this age of social media where we were being constantly bombarded with news from various outlets, nationally and internationally, we need to be mindful of the news source. A good self-care practice would incorporate having a routine, journaling and writing down your worries, talking to loved ones (by phone, text, social media or video) in a way that works for you, meditative practices (such as using guided meditations and listening to calming music), taking walks while practicing social distancing, talking through your fears by challenging anxious, irrational thoughts, and disrupting the anxiety spiral by using grounding techniques, utilizing your five senses, to bring you back into the present moment.

Recent Comments