By Len Lazarick

Kevin Kamenetz may have been buried May 11, but he remains very much alive on Democratic primary ballots.

The death of the Baltimore County executive as he campaigned for governor exposed problems with Maryland election laws, as well as long-standing constitutional issues with the job of lieutenant governor.

Here’s the apparent state of affairs now that his running mate, former Montgomery County Councilmember Valerie Ervin, has decided to take the option of running in his place, as provided in state law.

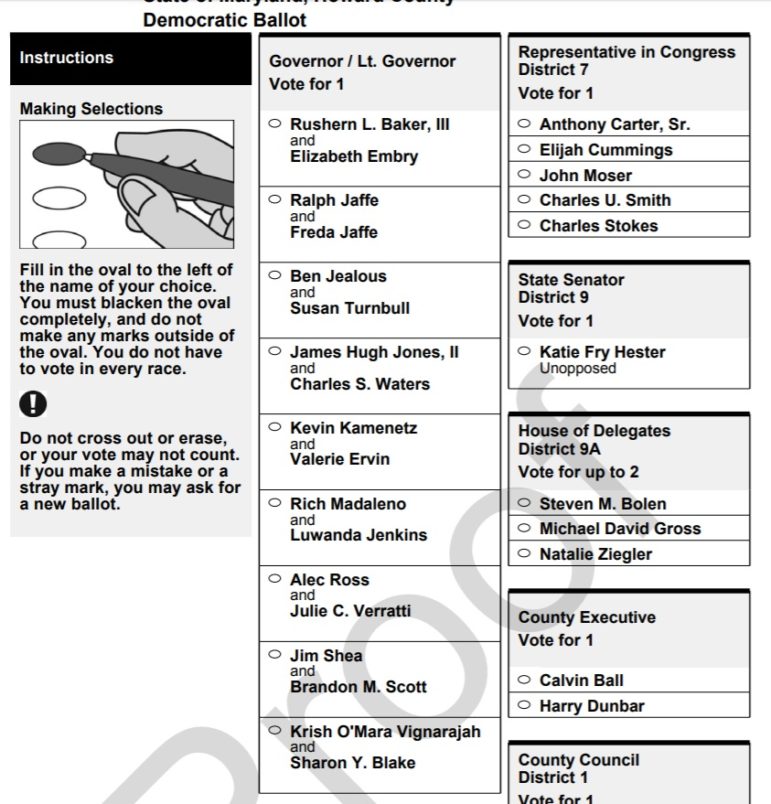

Her name will remain under Kamenetz on more than 2 million Democratic primary ballots. There is no time to reprint the ballots, officials say, and thousands have already been sent to absentees, particularly overseas and military voters. There may be some signs put in polling places to alert Democratic voters of the switch.

The primary is more than a month away, and maybe under the old electronic system, the polling cards could have been changed.

After a long fight, Maryland returned to scanned paper ballots because there was no paper trail allowing officials to recount the ballots, and many were concerned about the security of electronic voting. The Russian meddling has not lessened those concerns.

The Democratic ballot as it looks for governor, this example from a Howard County precinct.

Paper ballots an imperfect solution

Paper ballots are an imperfect solution. Voters are more likely to make stray marks that invalidate their choices or not vote for offices and candidates.

According to the state board of elections, there are 355 different ballot styles for Democratic voters across the state, meaning 355 press runs and now insufficient paper to reprint them all. Plus there are less than four weeks until early voting begins June 14.

Federal law has pushed the deadlines, sending ballots out earlier to make sure that overseas and military voters have enough time to cast their ballots and return them. Some may have already voted for Kamenetz.

A second huge obstacle for Ervin is that she may not use any of the millions that Kamenetz raised for himself, more than any other Democrat. The two may run as a team on the ballot, but except for a small joint account, they raised money on their own and separately.

As currently interpreted by the state board of elections, Kamenetz’s money can only go to charities or party organizations; returning it to donors is nearly impossible.

Choosing an LG

Kamenetz chose Ervin to run as lieutenant governor for many reasons — geographical, gender, racial and ideological. She is a black woman little known outside Montgomery County, and to his left with more appeal to Democratic progressives.

But this leads to the basic question: Why must candidates running for governor in their party primaries choose a running mate by the time they file for the office?

Candidates for president don’t choose their vice presidential nominee until they’ve won their party nominations, giving them a good shot of choosing someone who actually could step in for them if something happened.

Maryland’s current system forces candidates to choose someone willing to take a gamble on a statewide race with a possibility they might lose.

Of the nine Democrats running for governor this year, five have zero experience as a state or local official, elected or appointed. Five of their running mates have the same lack of governmental experience.

None of the Democratic candidates is particularly well-known outside his or her home base, even county executives from its largest jurisdictions, like Kamenetz and Rushern Baker of Prince George’s County. Their choices for lieutenant range from, “That name sounds familiar” to “Who the heck is that?”

Look no further than Ervin’s running mate that she had to find on short notice: Marisol Johnson, 38, who served as an appointed member of the Baltimore County school board for five years and withdrew from a County Council race in February.

Harry Hughes and Sam Bogley

The problem with the choice of lieutenant governor has been apparent for 40 years. In 1978, the first race for governor this writer covered, there was a crowded field of Democrats running for governor. They included Maryland’s first lieutenant governor of the modern era, Blair Lee III, who was able to snag Senate President Steny Hoyer as his running mate.

The others, such as Baltimore County Executive Ted Venetoulis and Baltimore City Council President Wally Orlinsky, were barely known outside Baltimore. And “a lost ball in high grass” as one pol described him, Harry Hughes had been transportation secretary and a Senate majority leader.

Hughes, a laid-back campaigner with little support, wound up picking an equally unknown Prince George’s County Council member Sam Bogley as his running mate. To the surprise of most, not just Lee and Hoyer, Hughes won, and became governor, only to find out that he and Bogley were completely at odds over abortion in an era when the issue was still a political battleground. Hughes favored abortion rights, Bogley strongly opposed it and got completely sidelined. In the next election, Hughes chose to run with Senate Judicial Proceedings Chairman Joe Curran, who would later become attorney general.

Strong candidates get experienced LGs

Strong candidates like Lee or Baltimore Mayor William Donald Schaefer running with Senate President Mickey Steinberg could pick experienced legislators as running mates. Lesser known candidates have to persuade others with less experience to come on board.

The 2014 election was an oddity. Four years ago, the party nominees for lieutenant governor, Republican Boyd Rutherford and Democrat Ken Ulman, had as much governing experience as the candidates at the top of their tickets, Larry Hogan and Lt. Gov. Anthony Brown.

(Didn’t Hogan have “no political experience” as he repeatedly claims as recently as an April 24 fundraising letter? Only if you don’t count his work in the campaigns of his father, Larry Sr.: for Congress, Prince George’s County executive and governor; also serving as an aide to the his county exec father; Larry Jr.’s own two runs for Congress, getting 45% against Hoyer one election, and his four years as appointments secretary to Gov. Bob Ehrlich, probably the most political job in the governor’s cabinet.)

Even an incumbent governor can have trouble recruiting a lieutenant for a job that has no inherent power. Seeking reelection, Ehrlich chose Secretary of Disabilities Kristen Cox, a blind Mormon from Utah who had lived in Maryland just a short time. (Lt. Gov. Michael Steele, Maryland’s first African American elected statewide, was running for Senate. Being LG for Steele, a former state Republican chairman, was his first elected office.)

Some have proposed eliminating the office of lieutenant governor altogether. That seems a bit extreme. At the very least, Maryland should allow its party nominees to choose their running mates after they win the nomination, and can have a better chance of getting someone really qualified for the job.

Lt. Gov. Boyd Rutherford presents the Woodlawn vase at the Preakness Saturday. Gov. Larry Hogan says he gave up his traditional duty so that Rutherford could also say he gave the prize to a potential Triple Crown winner, according to Hogan’s Facebook page. The Maryland Constitution simply says that the lieutenant governor “shall have only the duties delegated to him by the Governor.” This is one of the better duties. Screen shot from NBC’s broadcast on the governor’s Facebook page.

Recent Comments