This is the second part of a special project by the Capital News Service, “Reforming the Force: Can a broken police department operating under a federal consent decree be repaired?” Mayor Catherine Pugh fired Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis on Friday, leaving department veteran Darryl De Sousa as the new commissioner facing the task. Some think a focus on people, training and technology will work, but critics aren’t so sure.

By J.F. Meils and Allies Melton

Capital News Service

The problems began long before the death of Freddie Gray, the young black Baltimorean who in 2015 succumbed to injuries he received in police custody, sparking a riot.

But it wasn’t until the Justice Department investigation of the Baltimore Police Department was released more than a year later that the depth of the issues were revealed. The report’s pages, which are available with annotations here, told the story of a force failing at basic policing for years, if not decades.

Just a sampling of the report’s chapter headings include allegations of discrimination against African Americans; unconstitutional stops, searches and arrests; use of unreasonable force against juveniles; retaliation for speech protected by the Constitution; suggestions of gender bias; failure to hold officers accountable, and a broken relationship with the community.

In April, the city and Justice Department entered into a massive reform agreement, or consent decree, which step by step catalogues big changes the police department must make.

Amid rising crime in a poor city, Baltimore’s force must transform itself in almost every conceivable way, from its basic approach to policing and the technology it uses to the data it collects to the transparency and accountability it has historically shunned.

It must do all this under the gaze of an independent monitoring team overseen by a federal judge. And it must occur against the backdrop of a steady rise in crime that included the shooting death in November of Det. Sean Suiter, a death that locked down the surrounding neighborhood for nearly a week.

A city-wide crisis

Baltimore ended 2017 with 343 homicides, the third straight year the city experienced more than 300. Police also reported a significant rise in robberies and aggravated assault.

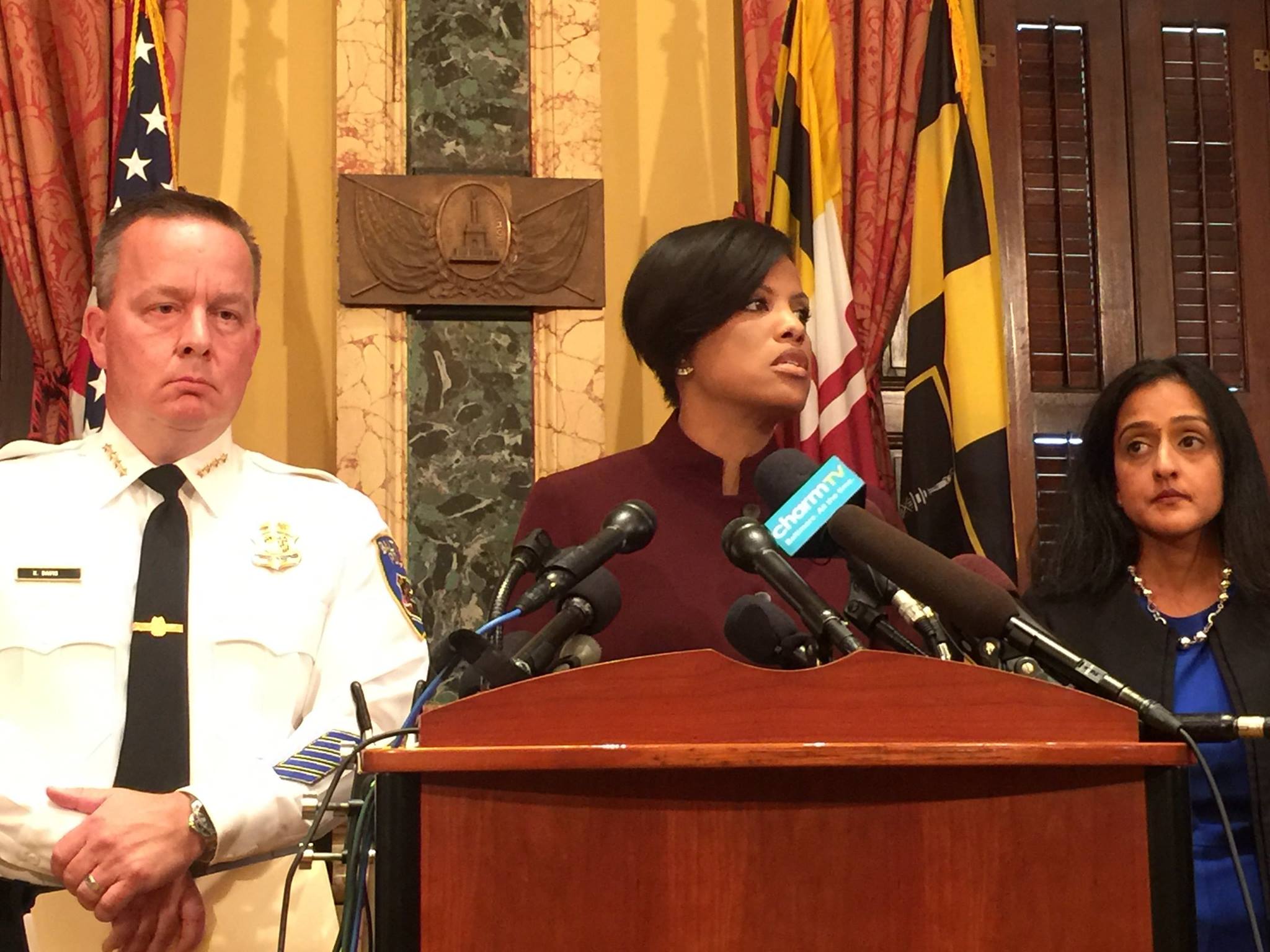

Baltimore Mayor Catherine Pugh fired Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis on Friday, citing the third consecutive year of more than 300 homicides.

“As I have made clear, reducing violence and restoring the confidence of our citizens in their police officers is my highest priority,” Pugh said Friday. “The fact is, we are not achieving the pace of progress that our residents have every right to expect in the weeks since we ended what was nearly a record year for homicides in the City of Baltimore. As such, I have concluded that a change in leadership is needed at police headquarters.”

She appointed Darryl De Sousa from within the department to take on the job of police commissioner, charged with simultaneously reducing crime and bringing the city into compliance with the Justice Department’s consent decree.

No federal funds were provided for complying with the Justice Department’s consent decree, which the city and the Justice Department signed in January 2017. A federal judge approved the agreement in April.

Without direct federal aid, the department is relying on city funds and state grants.

The police department’s budget for the 2018 fiscal year is $497 million, with more than $10 million earmarked for compliance efforts.

At 227 pages, the decree is 70 percent bigger by page count than the next largest, the one created for Ferguson, Missouri, which ran 133 pages. Baltimore’s 500-paragraph consent decree contains elements that require compliance before the decree will be lifted.

The initial term is five years, subject to indefinite renewals at the discretion of a federal judge who, along with a 20 plus-member monitoring team, oversees its implementation. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund released a letter to the monitoring team in November asking for focus on 20 key areas of the consent decree as well transparency throughout the process.

New Orleans, which agreed to a then-monstrous 129-page consent decree in 2013 following years of questionable policing, quickly learned that compliance is complicated.

“We have 492 paragraphs [in our consent decree],” said Danny Murphy, deputy superintendent of New Orleans Police Department’s compliance bureau. “For each one we had to do a deep dive, work with monitors to make sure we were on the same page. What is the compliance expected? How are we going to measure it?”

The Baltimore consent decree includes long, detailed sections that redefine the department’s overall style of policing, how stops, searches and arrests will be conducted and measured, as well as intricate new directives on the use of force, officer accountability, data collection and implementation of new technologies.

Despite the enormity of the task, Chief Ganesha Martin, who heads the police department’s efforts to comply with the consent decree, is undaunted.

“We started working on consent decree reform before there was a consent decree [in place]” Martin said. “I have been told that no other jurisdiction has been as prepared as we were and done as much pre-work on the consent decree without really having the mandate to do any of it.”

The legacy of zero-tolerance

Martin will oversee a sea change in the way policing happens in Baltimore. That means rewiring more than just police culture, but the culture around the police.

“After the [Freddie Gray] unrest, the attitude on the streets towards policed changed,” said Mike Hilliard, a 27-year-veteran of the Baltimore Police Department who retired in 2003. “People seemed to be less respectful and less afraid of them. The bad guys didn’t fear them anymore.”

For some, the issue that led to the violence after Freddie Gray’s death was not about fear or respect, but the legacy of so-called “broken windows,” or zero-tolerance, policing, where aggressive enforcement of small crimes is believed to deter bigger ones.

The policy, its detractors say, can ruin the relationship between the police and communities, as noted in the Justice Department’s investigation that preceded the consent decree.

In response to the prosecutions of the officers involved in the Freddie Gray arrest, some observers believe the police also began backing off some enforcement, frightened they’d be brought up on charges if they ended up in a similar situation.

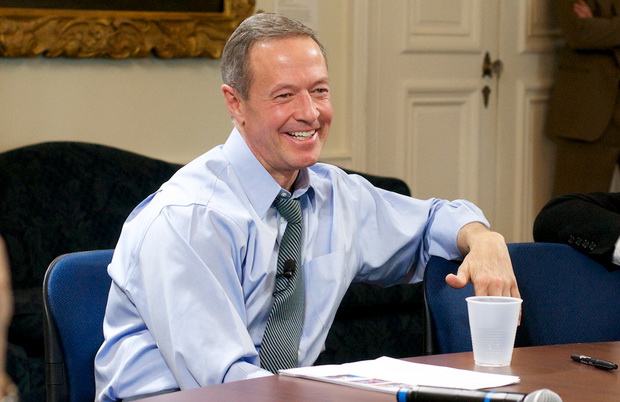

Baltimore used the zero-tolerance approach most notably from 1999 to 2006, under Mayor Martin O’Malley, who went on to serve two terms as Maryland’s governor.

“What we did here [in Baltimore] was just zero-tolerance all the time and that didn’t work,” Hilliard said. “It’ll drive down crime short term, but it kicks the crap out of the community, so you start losing your relationship with them that you had before, and that’s a problem between the community and the police.”

Martin O’Malley in his last press conference with reporters as governor.

O’Malley has been widely criticized since Freddie Gray’s death for championing zero-tolerance policing as Baltimore’s mayor, an approach many believe added to tensions between police and residents.

O’Malley disagrees, pointing to what’s written into the consent decree that he said were already policies implemented while he was in office, such as transparency on data.

“This is a 350-year legacy of race and injustice intertwined with law enforcement in our country,” O’Malley said in a Capital News Service interview, “and none of us is so good as a city so that we can escape that in three or four or five years of trying. You got to go out everyday and you actually got to do the work and embrace openness and transparency in policing.”

The Justice Department investigation that preceded the consent decree detailed widespread distrust of police among Baltimore’s black residents, including the city’s youngest.

“In a lot of our eyes, the police are just another gang on the streets,” said Shahem McLaurin, 23, who grew up in Baltimore and lives in McElderry Park, near the Johns Hopkins medical campus. “The difference is they just get away with stuff legally.”

McLaurin, who has launched the Baltimore Start Project, a youth organization in the city, said asking for help from the police “can be like a death sentence” in certain parts of town.

“We don’t look for police,” he added. “We avoid them.”

Baltimore City Councilman Brandon Scott, who chairs the council’s public safety committee, blames the system—specifically the city’s history of zero-tolerance policing.

“You can’t go through those [zero-tolerance] years of locking up so many people, and many of them for very minor things, and then not think it’s going to have a lasting impact,” Scott said.

And Del. Cory McCray, D-Baltimore City, points to a byproduct of that same style of policing—a lack of familiarity between cops and the communities they patrol.

The problems began, McCray said, when police “…just started whooping your tail instead of trying to get to know you.”

Civilian Review Board lacks power

The Justice Department investigation found that police officers are not consistently and appropriately disciplined.

Baltimore’s Civilian Review Board, created in 1999 and reconstituted with new members this year, is theoretically empowered to police the police by fielding complaints, investigating them and making disciplinary recommendations to the police.

However, the members don’t have any true ability to enforce discipline against individual Baltimore police officers. They can only investigate them and recommend disciplinary actions.

“I think there’s inherent bias when you have one person or one group of persons making decisions when there’s a conflict,” said Bridal Pearson, chair of the review board. “I think that’s antithetical to transparency.”

In the past, when a civilian review board recommendation conflicted with the police department’s own review, the commissioner went with the internal affairs recommendation nearly every time, said Jill Carter, director of Baltimore’s Office of Civil Rights.

Community groups like Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle worked to change the rules on who can serve on administrative trial boards, or those that are used internally to determine police discipline and are populated exclusively with police officers.

Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, along with other advocacy groups, helped change the law so it was no longer illegal for civilians to serve on trial boards. But the contract between Baltimore’s police union and the city expressly forbids it.

“They’ve baked in all these levels of protection from basic accountability to the community,” said Lawrence Grandpre, director of research of Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle.

“We have no trust that the immense power police have can ever be checked by administrative or legal mechanisms, as long as the community is isolated from the administrative process,” Grandpre said.

Baltimore Police 2.0

In May 2016, the city unveiled the $11.6 million body-worn camera program for police. In July, Baltimoreans watched body-cam video that appeared to show officers planting drugs they would later return to and declare to be evidence. Allegations like this and others led State’s Attorney Marilyn J. Mosby’s office to dismiss dozens of court cases that included testimony from the officers involved in the suspect body cam videos.

The department says that by the end of 2018, every sworn officer should be equipped with a body camera.

But the consent decree goes beyond training in new technology to include training in how police approach people.

All officers are mandated to attend “Fair and Impartial Policing” training, which will include topics like implicit-bias that help educate officers on their own prejudices and how to counter them in the field.

While all this is in process, the department is also trying to recruit cadets to a force in the middle of remaking itself. The department is down about 500 officers from 2012, Martin said. Recruitment, hiring and retention are focuses in the consent decree.

But with more than 2,500 officers, Baltimore’s police department is still one of the largest forces per capita in the country.

Broken Police Part 1: Police statistics on stops useless

The statistics that state law requires police departments around the state to file on stops and searches are incomplete and unreliable, a Capital News Service analysis has found. That has left the state without the tools to assess if minorities in Maryland are receiving fair treatment from police officers. First of four parts.

Reinventing and reforming black culture so that the excuse of “victimhood” is done away with and self-discipline and responsibility are taught and enforced…

As I write this ( 01/23 ), there have been 13 homicides for 2018…

The consent decree allowed Baltimore to escape being sued by the Feds based on adverse findings in DOJ’s Civil Rights Division’s assessment report. That report and underlying fieldwork were done by DOJ (largely HQ) personnel who excelled at all the nuances of civil rights’ caselaw but lacked policing experience. Conclusions were drawn from anecdotes (i.e. interviews) because the police didn’t keep auditable records and weren’t by law required to do so.

I’ve always been skeptical (for many reasons) DOJ’s assessment was objective. I don’t think the cops were scapegoated but it’s sometimes hard to tell from a report suffering from obvious methodological shortcomings. It is, however, too bad neither the mayor nor commissioner didn’t (or weren’t able to) challenge any of the report’s conclusions before the report was finalized. Now the city has subjected itself to an open-ended deadline under the heavy hand of the Federal judiciary to implement a set of findings prepared by civil rights counsel who’ve never walked the beat.

Reinventing police workflows, internal controls, IT systems and the policing culture will be very expensive. I’m surprised the city (and state) are able to bear this cost without Federal grant dollars.