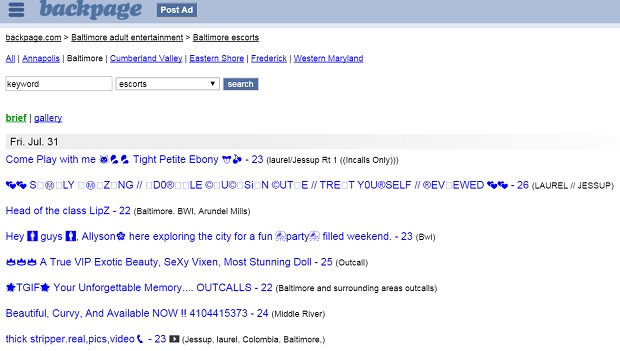

Photo above: Screen shot of Backpage escort ads

This is part 2 of a five-day investigative series on human trafficking in Maryland Capital News Service produced by student journalists and professional editors of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland College Park.

By Katelyn Secret, Jin Kim, Jessica Evans and Courtney Mabeus

Capital News Service

Behind the numbers on human trafficking arrests is a thriving underworld that depends on a steady stream of vulnerable women and minors for its profits.

To get a better picture of human trafficking’s reach and impact in Maryland, Capital News Services examined hundreds of pages of testimony and evidence produced in three dozen successful trafficking prosecutions over the past decade.

The traffickers aren’t always the flashy, bling-wearing, urban street pimps Hollywood portrays, the records show. They are sex salesmen who use business cards and online classifieds like Backpage to market their products. The business — often referred to by insiders as “The Game” — includes strategy and deception.

Ads on Backpage

Advertisements under the “Escorts” link on Backpage include erotic photos and descriptions of services by location. Last Friday, there were over 200 such ads posted for the Baltimore area (some were duplicates) and even more for the D.C. area.

“WeeKdaY SpEci@Ls SwEEt TrE@T PriCeS U CaN’t Be@T 18-18-18,” reads one Backpage posting submitted as evidence in a 2013 human trafficking case. Many provide ages, but authorities have found some of those listed in their late teens or early 20s are actually minors.

Not all ads are for prostitution, and not all prostitutes are under the control of traffickers. But the Internet, social media and mobile apps have allowed traffickers to reach a wide audience of victims and johns — and then disappear through Web wormholes when police try to track them down.

“In the past, all prostitution was run on the street,” said Montgomery County prosecutor Patrick Mays, who works on human trafficking cases. “Previously, there was a physical location in every city where girls would walk the street. Now it has completely changed with the Internet. Trafficking is all over the place.” (The Washington Post reported in late July that street-walking had returned to some parts of the District.)

Jeremy Naughton, of Oxon Hill, identified prostitutes who were working independently through their website ads, according to evidence presented at his 2013 federal trial in Baltimore. He then posed as a client and, once alone with them, pulled out a gun, seized their belongings, and forced them to prostitute for him in Montgomery County and in New York, prosecutors said.

He intimidated one prostitute into compliance by “snapping the neck of her dog with his hands,” investigators said. He was convicted of sex trafficking and weapons charges and sentenced to 36 years in prison. Naughton, now 34, is appealing. He told CNS through his attorney that he “never denied that he was in the business of prostitution, but the women who worked with him did so voluntarily.”

Drugs, dependency and brute force

While traffickers conduct much of their business in cyberspace, the methods for maintaining emotional control over victims are still largely old school: drugs, dependency and brute force.

A blurry surveillance tape from the early morning hours of Feb. 23, 2013, shows the garage of the Maryland Live! Casino: A slender woman stands in front of a heavyset man amid the parked cars. He suddenly swings his fist, delivering a blow to the side of her head that catapults her several feet, stumbling.

He pauses before walking over to connect more punches, striking her in the face as she crouches to shield herself.

According to court records, the woman, referred to as J, was a prostitute; the man, Michael Wesley Lee of Odenton, was her pimp; and the beating was punishment for failing to attract enough customers at the casino to have sex with her.

While Lee sat in an Anne Arundel County jail on an assault charge, his partner, Robert Downing, also of Odenton, took J to a hotel to have sex with customers to raise money for Lee’s bail, the records say.

J escaped when Downing left her alone. She declined to press charges, and the assault case was dropped, records show.

Enticed from St. Louis

Six months after the assault, in August 2013, Lee used the social media website Tagged to entice S, a 23-year-old woman living in St. Louis, to come to Baltimore with the promise that she could work for his “webcam business,” according to court documents. Lee bought the woman a $208 one-way Greyhound bus ticket and she traveled to Maryland in August 2013.

After she arrived, Lee revealed the truth: He was really a pimp with women in several states working for him, court records say. He took her to a Microtel in Linthicum Heights, confiscated her identification — a common ploy by traffickers — and told her she needed to pay off the ticket and a $1,000 initiation fee, court records say.

S “was afraid to challenge Lee because of his size and his demeanor,” and had no money of her own, the records say. By the next day, she’d had sex with 10 different clients and charged rates as high as $200 — but he kept the money, some of which was used to place advertisements on Backpage, records say.

Around the same time, he lured M, a 21-year-old exotic dancer to the hotel on the pretense that he would get work for her at clubs, according to court records. When he tried to force her to stay to prostitute for him, she ran from the hotel, records say. He chased her, but she escaped by hopping a fence.

S got away several days after M by calling 911 for an ambulance from an Extended Stay hotel near Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport. When the ambulance crew arrived, she told them about Lee and they called police, who arrested him, according to court records.

Lee, now 31, pleaded guilty to federal trafficking charges and was sentenced in March to 13 years in prison. Downing, now 46, pleaded guilty to a federal charge of using interstate facilities to promote and facilitate a prostitution business and received a 46-month term. Both men declined to be interviewed by CNS.

Parent trap

Single mothers make an especially vulnerable target for traffickers. Pimps often use the children as a soft spot to exploit — either offering a way to support the child or threatening the child if the mother refuses to meet their demands, court records show.

R left her parents’ home in a small Guatemalan town at 17 for the United States. She was raped in transit and gave birth to a baby girl after arriving in America, she later testified in federal court.

She took a job in 2006 making around $400 a week at a recycling plant in Prince George’s County and moved to Langley Park, a landing spot for many Central American immigrants who arrive without legal immigration papers. A man spotted her at a restaurant and offered to pick up the bill. She refused. But within weeks, the two were dating, she said in court.

He told her that he was in construction, that he was a painter, she said. His aunt could care for her baby at her house while she worked. Three months into their courtship, with her baby under his control, he told her how he really made his money: “Selling women,” she testified.

And soon R, in fear for the baby’s safety should she say no, was working for him.

She became one of the prostitutes in a brothel the man had set up in a house in the Washington suburbs, she said in federal court.

German de Jesus Ventura, 37, was convicted on federal sex trafficking charges in 2013 and is serving a 35-year sentence. Photo courtesy Annapolis Police Department. Capital News Service Photo Illustration

Then she met German de Jesus Ventura. He was a client who told her he would take her away from this life and take care of her and her daughter, R said. She wouldn’t have to prostitute anymore if she came with him, she said.

At the beginning, their relationship was “very perfect,” she said.

Then one day, Ventura tossed her a box of condoms and told her it was time to get to work. When she refused, he beat her, she testified at his 2013 federal trial in Baltimore on trafficking charges.

Ventura didn’t just run prostitutes – he controlled them with violence, and used them to build a network of brothels, according to court records.

“I didn’t want to have sex with men,” R told the court during Ventura’s trial. She told how he would threaten her and the other prostitutes with guns, how he abused her “with his fists and a belt” when she resisted him.

Kevin Garcia Fuertes is serving a 20-year sentence in federal prison after his 2013 conviction on sex trafficking charges. Photo courtesy Annapolis Police Department. Capital News Service Photo Illustration

“He would beat me and tell me that he was going to kill me,” she said.

Court records outline how from March 2008 to November 2010, Ventura and his partner, Kevin Garcia Fuertes, expanded their prostitution business from a small brothel in an Annapolis apartment to a major sex trafficking ring that operated out of residential neighborhoods and sprawled across the borders of Maryland and Virginia.

Attracting customers with business cards

To attract customers, he used accomplices to distribute business cards advertising “deportes” or “sports” in the vicinity of his brothels, records say. These cards signaled to seasoned patrons where to find prostitutes.

Paper tally sheets scrawled by Ventura and later confiscated by authorities, recorded whether each girl was reaching her quota – as many as 30 men a day. One 15-minute session typically cost $30. The women were allowed to keep half of those proceeds, according to trial testimony.

Despite at least one police raid, in 2008, the prostitution operation carried on for two more years before a joint investigation by federal and state law enforcement gathered enough evidence to arrest Ventura and Fuertes on sex trafficking charges. It took court orders to track cell phones and surveillance to photograph Ventura transporting women for prostitution, records say.

A jury convicted Ventura, now 37, of sex trafficking. He was sentenced to 35 years in prison. His case is on appeal. Fuertes, now 27, also was convicted of sex trafficking and sentenced to nearly 20 years.

Neither man could be reached for comment. At his sentencing, Ventura said, “I have never sold prostitutes” nor harmed anyone and that “the only thing I did with Ms. [R] was to help her.”

At the time of the trial, R had obtained a work permit and found a job as a laborer in construction. But her baby had been taken during the 2008 police raid of Ventura’s brothel, she testified, and legally adopted by another family.

Runaway problem

Runaways are among the easiest targets for traffickers, advocates say: Many come from troubled families and unstable living situations. They’re often on their own without money or shelter.

“These victims are looking for somebody who’s there to pay attention to them and somebody who might be the first person in their life to offer them the care, support and love that they’re looking for,” said Alicia McDowell, executive director of the Araminta Freedom Initiative, a Baltimore anti-trafficking advocacy group.

Harvey Mojica Washington was charged in state court with misdemeanor human trafficking, sexual assault of a minor and other charges stemming from his recruitment of C, a 14-year-old runaway, for his prostitution business in January 2012. The trafficking charges were dropped, and he pleaded guilty to a third-degree sex offense, a felony.

At his sentencing hearing in March 2015, Prince George’s County Assistant State’s Attorney Christina Caron-Moroney said that Washington fed and clothed C for a few days after picking her up off the street before revealing the real price of his attention: prostitution.

She was shown how to post ads on Backpage to attract clients and how to turn tricks, the prosecutor said. Washington instructed her to sleep with men in cars in a parking lot until she raised enough money to get a hotel room, she said.

The girl contacted friends through Facebook to tell them she was unhappy with what she was doing and wanted a way out. When Washington found out, he “became violent with her,” Caron-Moroney said at the sentencing. Her mother sought the FBI’s help and, through her friends, agents tracked her down in February 2012.

Washington, now 31, was sentenced to 10 years in prison with five years suspended.

“This is the time for excuses and reasoning, and I have neither,” Washington said, voice weak, at his sentencing. “I’m not opposed to any sentence, I’ll do whatever I have to do.”

C decided not to testify in person at the sentencing. The girl had spent more than two years in a treatment facility for post-traumatic stress disorder following her ordeal, Caron-Maroney said. So the teen wrote a letter to the court, which the prosecutor read aloud.

“I am not his first victim of this type, but I would like to be the last,” C wrote. “I couldn’t sleep for months thinking this man would be free and come and find me or my mom and little brother.… He puts girls in this situation, takes away their pride, and joy of becoming a woman just to make money.”

Lisa Driscoll, Jon Banister, Fatimah Waseem, Hayley Goodman and Melanie Kozak contributed to this article.

We are hoping to build a safe house in Northern Kentucky next year to house women that want off the streets and want a new start in life.