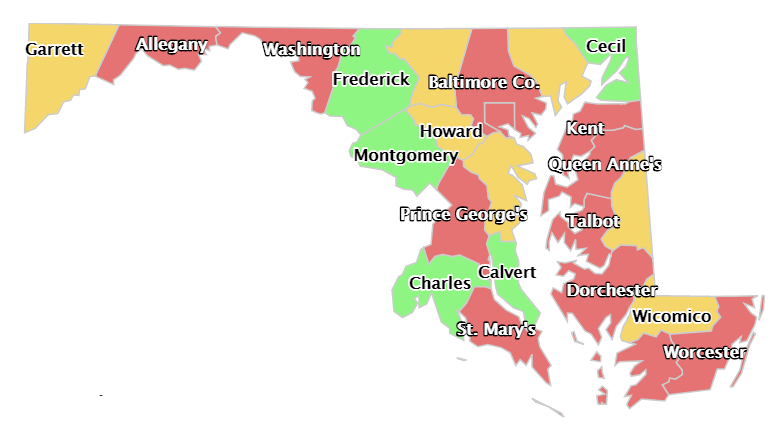

For the interactive version of this map showing percentages and trends for each county click here. Green is 90% funded or above, yellow is 70 to 90% funded, red is below 70%.

By Carol Park

Maryland Public Policy Institute

Given the scarce media attention on Maryland state government’s public pension crisis, which includes a $19.7 billion shortfall, Marylanders could be forgiven for not knowing that their local governments also face daunting unfunded pension liabilities.

With unfunded pension liabilities growing every year at both local and state level, Maryland can no longer ignore the problem.

The Maryland Public Policy Institute recently launched the Maryland Pension Map to shed light on how well local pension plans are funded. The interactive map displays the size of the net pension liability and the funded status of each county that have their own pension systems. The map also shows the historical trend of how each counties’ unfunded pension liabilities have grown over the years.

In 2017, Ken Decker, Caroline County Administrator, wrote an article for MarylandReporter.com called ‘Maryland should look to local government for pension solutions.’ Decker suggested that potential solutions to Maryland’s pension crisis may be found by looking at what local governments have done. Caroline County’s pension system health had improved from less than 65% funded five years ago to over 81% funded in 2017.

However, a close analysis of the Maryland Pension Map reveals that Caroline County is one of the few Maryland counties where pension systems fared reasonably well in recent years.

No counties fully funded

According to our map, none of 23 counties’ and Baltimore City’s pension plans were fully funded as of June 2017. Only five had plans that were over 90% funded.

Even worse, 14 out of 23 counties saw pension liabilities improve from FY 2014 to FY 2017. All of the five biggest Maryland counties by population, Montgomery County, Prince George County, Baltimore County, Anne Arundel County and Howard County, experienced a decline in the funded status. Among the five, Baltimore County experienced the steepest deterioration from 68.2% funded in FY 2014 to 61.46% in FY 2017.

Out of all localities, Washington County, Prince George County and Baltimore County face the biggest pension crises. As of June 2017, Washington County’s pension plan was just 49% funded, compared to 77.4% funded three years earlier. Baltimore City also has rapidly declining pension health. From FY 2014 to FY 2017, the average of all of Baltimore City pension plans deteriorated from 72.6% funded to just 65.5% funded.

Pension problem real at local level

Our online map serves to remind Maryland taxpayers and policymakers that pension problems are as real at the local level as they are at state level. Local officials created this crisis in the same way state officials did: spending millions in Wall Street fees to manage risky funds only to reap mediocre returns while refusing to increase member contributions at a rate required to cover rising costs.

For instance, Baltimore City Employees’ Retirement System pension managers spend around $9 million every year to invest in a risky portfolio but its 10-year annualized return of 5.4% underperformed a composite passive index of public stocks and bonds. Meanwhile, the plan’s member contribution remained a mere 3% instead of the planned increase to 4% for FY 2017.

Underperforming funds and low member contribution typically mean taxpayers are burdened with making larger contributions to keep pension promises to public employees. For Baltimore City’s Fire and Police Employee Retirement System, the city’s contribution increased from $114 million in 2014 to $130 million in 2017.

A depressing vision for Baltimore

The Maryland Pension Map reveals a depressing vision for Baltimore, not just for the taxpayers but for the city’s overall attractiveness. Every dollar used to plug a hole in a city’s retirement funds is a dollar not spent on classrooms, police officers and other services.

This daunting reality is hardly limited to Maryland. According to Professor Sarah Anzia of the University of California Berkeley, 85% of the cities across the U.S. saw increases in their pension expenditures between 2005-2014. Skyrocketing pension costs have played a major role in forcing local government officials across the nation to make painful decisions about pension benefits, service provision and taxes.

Whether by increasing member contributions or reforming the way the counties invest their pension funds, local officials should not wait any longer to secure the retirement of its employees and protect taxpayers. Cutting employees’ benefits, decreasing services or increasing taxes in the future are neither morally justifiable nor lawfully viable options for fixing the localities’ pension problems.

Carol Park is a senior policy analyst at the Maryland Public Policy Institute.

A few years ago Baltimore City amended it’s pension plan. One of the changes was to permit employees to choose between a fully defined contribution option (basically a 401k with a substantial mandatory contribution) or a “Hybrid” option with a smaller pension payout than the old system.

I would love some commentary from real pension experts on how this change is likely to impact the city’s pension finances.