By Sydney Clark and Victoria Lorren Daniels

BALTIMORE—Larry Thompson, a junior at Reach! Partnership School, in the city’s Clifton Park area, counts at least nine friends who died in the last two years — shootings, stabbings, a car crash, a drowning.

“I’ve been losing friends back to back,” he said.

These teenagers deal with trauma every day.

Deaths are announced over the school intercom.

Classmates decorate the dead students’ lockers as memorials, grim reminders of the school’s losses.

Many students “are desensitized to everything,” said Tanasia Thomas, 17, a rising senior. They see no need to confide in anyone about their fear and sadness. “They think that it’s normal and don’t want to talk about it.”

But in school on a Monday in March, back before schools were closed because of the coronavirus, Thompson and Thomas were meeting with Wesley D. Hawkins, who had come there to hear how they were doing.

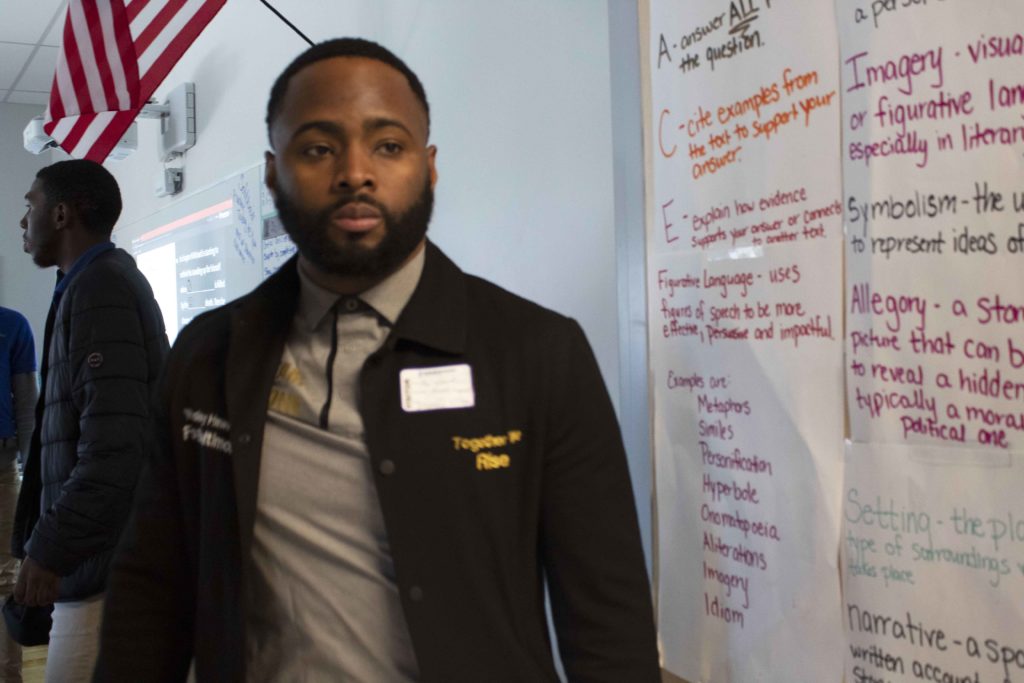

Wesley Hawkins, founder of The Nolita Project, walks into Reach! Partnership to check in with students he mentors in spring 2020. (Photo by Victoria Daniels/Capital News Service)

Hawkins, 34, is the founder of The Nolita Project, a nonprofit named in tribute to his late mother, Nolita Smith, who he said died because of a crack cocaine addiction in 2015.

The organization aims to provide support and guidance to young people who are facing some of the same struggles he endured. It is one of many small projects around Baltimore created to help teenagers get through school despite living with obstacles.

Terry Williams, who works with teenage boys through his nonprofit Challenge 2 Change Inc., admires Hawkins and his work.

“He has a way of transforming these young people’s lives out here,” said Williams, known as “Uncle T” in East Baltimore. “And he has a unique way of reaching them.”

The Nolita Project’s program structure is indeed unconventional.

Hawkins doesn’t ask students to come to his office. He goes to them, no matter where they are.

Hawkins understands how important it is for a child to know someone is backing him.

He said his aunt, grandmother and others who invested in him helped him push through high school and college and on his way to a master’s degree.

“If someone didn’t take a chance on me, I would still be in the streets,” Hawkins said. “If we don’t get out here and take the chance and invest in these children, then what?”

And so, on that Monday before schools closed statewide, Hawkins checked in at the Reach! Partnership front desk and strolled down the hall to find Thompson and Thomas. Staff and students approached Hawkins for handshakes and greetings.

“Hey, Hawk,” a staffer said. “How you doin’, man?” And then a student: “What’s up, Mr. Hawkins?”

Amid jokes and laughs, Hawkins walked with the students to a meeting area. There they sat as Hawkins asked the students for updates on their lives, what they did over the weekend and how they were feeling going into the week.

A stream of alarming texts

Thompson, 18, said he met Hawkins at a school event. Hawkins was promoting The Nolita Project and handing out contact information.

A few months later, angry and uncertain how to cope,Thompson found Hawkins’s phone number one night and started to text.

Hawkins said he woke up about 11 p.m. to a stream of alarming messages from Thompson and headed to Thompson’s house.

By the end of the night, after listening to Thompson describe his problems, Hawkins picked up food from a corner carryout. Soon, Thompson was eating a cheesesteak and in better spirits.

That was two years ago, and in Hawkins’s words, “We’ve been rocking ever since.”

Hawkins “made good on his word” to be there for him when he needed it most.

Thompson still calls Hawkins when he has low moments. He said he has anger problems but has become a better person since meeting Hawkins.

Thompson is the second oldest of five children in a home with no father. His older brother is in prison, and Thompson said he blames that on the fact that the family lacked a consistent male role model.

“He had to learn to be a man through himself and it messed him up, messed it up mentally,” Thompson said.

So Thompson takes his role as the oldest man in the house seriously. He recalls feeling he and his siblings had no one there for them.

He believes that if certain things hadn’t happened to him, he wouldn’t be who he is. Still, “It’s hard for you to learn from the things you’ve been through.” He paused, as if he was finding it hard to continue.

And then: “I’m thankful for what I got because some people ain’t even sleeping under a house…at the end of the day, you could be in a worse predicament than this.”

Thompson has plans for college and wants to study architecture at a university out West, hoping to get away from Baltimore. Then, he said, he wants to come back and “make Baltimore better.”

Tanasia Thomas and Larry Thompson, Reach! Partnership High School students, talk with Wesley Hawkins during their weekly session in spring 2020 (Photo by Victoria Daniels/Capital News Service)

Thomas and Thompson have been close friends for over two years. “I try to keep him in check,” Thomas said, smiling and shaking her head at him. Thompson nodded and said he could not remember the last time he skipped school. They hold each other accountable.

Thomas was the first girl in The Nolita Project from Reach! Partnership. She said that Hawkins is “extra support.” And she said the project introduces them to new experiences and people, through projects such as community clean-ups and trips, including one to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

“It’s better than just sitting, being outside or doing something you not supposed to do,” she said.

When Thomas realized she was having trouble coping, she went to a guidance counselor. She said her grades were bad, and she had begun fighting at school.

She said she was lucky to have found a guidance counselor who would listen and help.

As the oldest child of four, “I don’t get all the attention I need,” she said. “And it’s a lot of responsibility.”

She wants to make sure that her 16-year-old sister doesn’t get into fights, and she worries about her little brother. He’s only 5.

“I don’t want him on the streets. I don’t want him selling drugs. I want him to stay in school. I don’t want to have to think about is he going to die when he gets older…. I don’t want to have to think about none of that with him.”

Hawkins understands. “Being a black male in Baltimore is really, really heavy.”

‘I’m from it. I know how it is’

Hawkins said the students he works with live in areas where violence and drugs are common. The majority of the kids he has mentored live in single-parent homes, have a parent in prison, or have a parent who is dead, sick or mentally challenged, he said.

Today, this technique of talking to teenagers where they live and go to school remains at the forefront of his mission. But mentoring students in rough communities isn’t for the weak, he added.

“If you’re scared and afraid of their communities in the areas and the spaces that they grow up in, how can you reach them? That’s where they feel comfortable, that’s where they’re at. So my frame was: I’m from it. I know how it is,” Hawkins said.

As a child, he said, he witnessed his mother’s heavy drug use and her determination to get high.

Hawkins said his mother hid crack vials in his diaper because she knew police weren’t supposed to search children.

As a teenager, he said, he did what he knew best. He hustled, sold crack and marijuana and often got into fights.

When talking to the students he mentors, Hawkins is transparent about his past. He said it’s important for them to see an example of someone who survived the streets and has returned to try to keep teenagers off them.

“I wanted to no longer be a part of the problem,” Hawkins said. “I wanted to figure out how I could do something to help my community because I realized, how dare I sell another illegal product or any drug when those are the things that destroyed my family.”

He began talking with students on their way to class. Hawkins was consistent with his street mentoring. Students began expecting to see him before school and then after school.

Hawkins said people take notice when someone repeatedly shows up at the same place and time. Chatter from students about Hawkins started building. Hawkins said schools started inviting him to talk to students.

His speaking engagements expanded to churches and recreation centers. He said he was encouraged to take his message into schools.

But Hawkins didn’t have an education degree, so he couldn’t teach. An alternative was to become a Baltimore city schools vendor, offering his services in specific schools.

He said he became a vendor during the 2015-2016 school year and was approved to partner annually with schools that grant him weekly time with his students during the school day.

For the 2019-2020 school year, Hawkins has agreements with Reach! Partnership and Fort Worthington Elementary/Middle School. He is not paid this year for his work at Reach! Partnership.

For the 2018-2019 school year, Hawkins had a contract with Fort Worthington for $23,000. A new contract was in the works before the coronavirus led schools to close.

Darren Rogers, founder and executive director of I AM MENtality, also works with young Baltimoreans. He calls Hawkins his brother.

“He brings in a lot of good qualities to the work we do.” Rogers said

He “is a good servant, and good servants make good leaders,” Williams said.

‘The father I never had’

Chianta Harris’s 15-year-old son Alvin went through about five different community programs before she met Hawkins five or six years ago.

Harris said she pulled her son out of all of the programs because she felt their heart and commitment weren’t in it.

“I’ve had programs that would come, sign him up and then I’ll never see them again. I could barely get them to spend time with him,” Harris said.

Hawkins, however, has been there “from day one.”

Alvin’s father died when he was 2 years old, Harris said. Alvin calls Hawkins “the father I’ve never had.”

When Hawkins started Nolita eight years ago, he was one man talking to students before school on Belair Road. Today, he said, 10 to 15 volunteers assist Hawkins with mentoring students.

The Nolita Project was certified as a nonprofit in 2017, and Hawkins said funding comes from five to seven people who donate money each month. The nonprofit’s 2017 tax forms, the most recent available, show the project brought in $6,750 that year.

Nolita members participate in landscaping projects and local clean-ups to learn how to curb pollution and protect the environment.

Hawkins said the community projects encourage students to build relationships with others and to fulfill the service hours that the state requires of high school students.

The Nolita Project has also worked with community programs that train teenagers how to livestream sporting events where students learn videography and editing skills.

On that March visit to the Reach! Partnership, he walked Thomas and Thompson back to their classrooms. Before the students entered the room, he turned to them and asked if they had their classroom assignments.

He told them he would see them soon.

Recent Comments