By Timothy B. Wheeler

Bay Journal

What if the dead zone that plagues the Chesapeake Bay could be eliminated now, not years down the road — and at a fraction of the billions being spent annually on restoring the troubled estuary?

Fanciful as it sounds, Dan Sheer figures it’s technically doable. Whether it’s the right thing to do is another question. Bay scientists are wary of potential pitfalls, but some still think it’s worth taking a closer look.

Sheer, founder and president emeritus of HydroLogics, a Maryland-based water resource consulting firm, has suggested that the oxygen-starved area down the center of the Bay could become a thing of the past if enough air could be pumped into the depths and be allowed to bubble up through the water.

“It pretty much gets rid of the problem,” he said during a recent presentation to scientists at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. And it’s not just him saying that. The federal-state Chesapeake Bay Program ran his oxygen-bubbling calculations through the computer model it uses to simulate water quality in the Bay, and the preliminary results appear to back him up.

Algae blooms produce dead zone

The dead zone, as it’s called, is produced when algae blooms fed by excessive nutrients in the water die and decay, consuming the dissolved oxygen that fish, crabs and shellfish need to live. This zone of low to no oxygen forms near the bottom in the deep trough down the center of the Bay every spring and grows through summer, until finally receding in fall when algae growth ends.

The Bay Program has been laboring since the 1980s to reduce nutrient pollution and raise dissolved oxygen levels enough to eliminate the dead zone, but the effort has been costly and challenging.

The region missed two earlier cleanup deadlines and is now working toward another target date of 2025, when all projects and programs needed to meet nutrient reduction goals should be in place. That’s looking increasingly unrealistic as well.

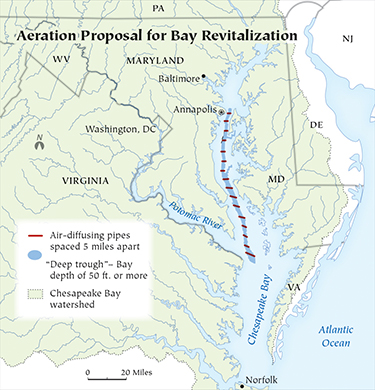

Aerating the Bay would be quicker, Sheer contends, and potentially less expensive. His idea: Lay 16 pipes across the deepest part of the Chesapeake at 5-mile intervals from Maryland’s Bay Bridge to the Potomac River, with a series of openings in them to release streams of tiny air bubbles. The oxygen in the bubbles would dissolve into the water and help sustain aquatic life.

Not a new proposal

Sheer isn’t the first to suggest bubbling the Bay like an aquarium. It’s been brought up repeatedly over the last 30 years, only to be dismissed as unworkable and inordinately expensive — harebrained, even.

In the late 1980s, Maryland tested floating aerators in a cove off the Patuxent River, but gave up after they produced a barely detectable change in oxygen near the bottom.

In 2011, the nonprofit Blue Water Baltimore, in partnership with a consulting firm, placed a small aerator in Baltimore’s harbor, with similar results.

Aeration has been used with some success elsewhere in freshwater lakes and reservoirs that suffer from nutrient pollution. And, it has helped water quality in some rivers, such as the Thames in the United Kingdom.

Pumping air into big open bodies of tidal water is more problematic. Scientists in Sweden and Finland have looked at and tested aeration as a possible remedy for severe algae blooms in the Baltic Sea. But they’ve held back from trying it on a large scale, in part because of uncertainty about its costs and effectiveness.

Given that history, reaction to Sheer’s proposal has been mixed.

Lot of questions

“I’m enthusiastic about the idea in a lot of ways, but there are a lot of questions,” said Bill Ball, director of the Chesapeake Research Consortium, a nonprofit that coordinates Bay studies among seven universities and labs in the region.

“I’m enthusiastic about the idea in a lot of ways, but there are a lot of questions,” said Bill Ball, director of the Chesapeake Research Consortium, a nonprofit that coordinates Bay studies among seven universities and labs in the region.

Sheer, who holds a doctorate in environmental engineering from Johns Hopkins University, said the idea of aerating the Bay mainstem came to him about 18 months ago while listening to a presentation at UMBC about the costs and complications of the federal-state restoration effort. When he stood up and asked why not try bubbling the dead zone away, he said others in attendance ticked off a litany of flaws they saw in his proposal.

“The room sort of turned into a shooting gallery,” he recalled, “and I was the target. I had lots of objections … ‘you’re fixing the symptoms and not the problem,’ ‘you can’t possibly pump enough air,’ ‘it’s way too expensive, takes too much energy’” and more.

After that, Sheer set out to see if his critics were right.

“It looks like it really will work,” he said.

Working at Rock Creek

Aeration has successfully treated low-oxygen conditions in Maryland’s Rock Creek, where they caused a rotten egg odor and prompted complaints from local residents. Anne Arundel County is currently replacing the original aerators at a cost of approximately $1 million. Bay Journal photo by Timothy Wheeler

Sheer pointed out that aeration has long been in use in one small corner of the Bay watershed, where he happens to keep his sailboat.

Rock Creek, a tributary of the Patapsco River near Baltimore, has had aerators since 1988. They were put there in response to complaints about the rotten-egg odor given off by the creek in summer.

A 2014 study by researchers with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science rated the Rock Creek aerators a success. They raised oxygen levels near the bottom enough to stop hydrogen sulfide from bubbling out of the sediments — another byproduct of low-oxygen conditions.

“The aerators were incredibly effective at restoring dissolved oxygen to the creek,” said Lora Harris, an associate professor at the UMCES Chesapeake Biological Laboratory and lead author of the study. Water quality improved even downstream, she said, nearly to the mouth of the tidally influenced creek.

Rock Creek is relatively shallow and small, compared to the water bodies where aeration has been tested before. The aerators there also were placed on the bottom, rather than floating on the surface.

The Rock Creek aerators cost $285,000 to install and about $7,000 a year to run, according to Janis Markusic, a planner with Anne Arundel County’s watershed restoration office. The county is now replacing the original aerators, she said, to the tune of $1 million.

Might cost $10-20 million

Doing it in the Bay mainstem would likely cost much more. Working with scientific colleagues, Sheer has estimated that it would cost $10 million–$20 million to install the piping network, bubble diffusers, air compressors, oxygen generators and other equipment. To run it would take another $11 million a year, by their estimates, with much of that spent on electricity to power the air compressors, pumps and other equipment.

While not cheap, that’s far less expensive than the current Bay cleanup tab, Sheer pointed out. In fiscal year 2017 alone, the six Bay watershed states and federal government spent nearly $2 billion on the restoration effort, according to Bay Program figures.

Sheer said the Bay Program model runs showed his aeration proposal would do just as much to raise oxygen levels in the Bay’s depths as the last round of nutrient-reducing cleanup plans drawn up by the watershed states and the District of Columbia.

The model also indicated aeration would actually outperform the Bay pollution diet in another, important way. Artificially increasing oxygen levels would reduce the release of algae-fueling phosphorus and nitrogen back into the water from bottom sediments where they had built up over time. That recycling of nutrients from the sediments has long been viewed by scientists as a potential hindrance to the Bay restoration.

A lot we don’t know

Scientists with whom Sheer has consulted — and Sheer himself — are quick to point out that his proposal relies on some unproven assumptions and could have unintended negative consequences, what engineers and scientists call “revenge effects.”

“There’s a lot we don’t know,” Sheer said. “There’s a lot we think we know that might be wrong.”

Ball, an environmental engineering professor at Johns Hopkins, said that from his experience with aeration in wastewater treatment plants, he’s not sure how well bubblers will work at raising oxygen levels in the Bay’s depths.

“He’s relying a lot on the sloshing of the tides,” Ball said, adding that “there’s a lot more work to do to figure this out.”

Jeremy Testa, an assistant professor at the UMCES lab, called the Bay Program model results “intriguing,” particularly in regard to limiting the flux of nutrients back into the water from sediments. But there are potentially significant downsides, he said.

One is that if the current rate of nutrient pollution isn’t reduced, he said, the phosphorus and nitrogen may simply continue to build up in the sediments, and then pour out into the water in one huge algae-blooming pulse if the bubblers ever shut down, even for a short spell.

That’s what Lora Harris said that she, Testa and other colleagues found at Rock Creek. They also found that the creek was emitting significantly more nitrous oxide — a climate-warming greenhouse gas — than other comparable water bodies.

There’s even a possibility, Harris noted, that pumping oxygen into nutrient-enriched waters could increase the formation of toxic methylmercury, which can build up in fish and is already one of the top two causes for fish consumption advisories in the Bay.

There’s also some concern that a series of aerators would create “bubble curtains” in the water that would impede fish movement.

“You never know what’s going to happen when you start manipulating the environment,” Testa said.

Treating the symptoms

Others say that even if technically feasible, aeration is just treating one of the symptoms of a distressed Chesapeake without fixing the causes of its woes.

While aeration could engineer a remedy for low dissolved oxygen, Testa warned that if nutrient pollution isn’t reduced, “we’re still going to have problems” with algae blooms, sediment-clouded water and important habitat like sea grasses not getting enough light to grow.

“Frankly, from a policy perspective, I think it’s a horrible idea,’’ said Beth McGee, director of science and agriculture policy with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. It would “let people off the hook,” she contended, weakening public and political pressure to make pollution reductions that would benefit the whole Bay watershed, including its rivers and streams — not just the dead zone.

Indeed, the 2014 Bay Watershed Agreement lays out 10 different goals that go beyond improving water quality to seeking such things as sustainable populations of fish, shellfish and black ducks, increased conservation of land and enhanced public access to the Bay and its tributaries.

‘Horrible idea’ or worth a try?

Sheer acknowledges that aeration is not a substitute for the nutrient and sediment reductions states are having to make under the Baywide Total Maximum Daily Load set in 2010 by the EPA. But rather than sap public interest in saving the Bay, he suggested that it could actually boost it. “If you have a big success,” he said, “maybe you’ll increase momentum to finish the job.”

Lewis Linker, acting associate director of the EPA’s Bay Program office, said that model runs testing Sheer’s proposal are very preliminary and need much more study. But he said “no way, no how” would he see aeration replacing the restoration effort’s current multi-goal approach.

At best, Linker suggested, aeriation might serve as an “add-on,” after all needed pollution reductions have been made, to help maintain healthy oxygen levels in the Bay’s mainstem even under extreme weather conditions.

The only way to find out if aeration can help, Sheer said, is to test the idea someplace in the Bay, with a pilot project costing around $2 million.

“This is not ripe to go out and do,” Sheer said, “but it is ripe, really ripe to go out and do a pilot. … I really think what we need to do next is put a station out there and see what the hell happens.”

Some of the scientists with whom Sheer has consulted agree that for all its potential pitfalls, it’s still worth further study.

“It’s not necessarily the complete solution,” Harris said, to the Bay’s nutrient overenrichment. But, she said, “It’s potentially nudging one of the symptoms that we do care about. …We have an obligation to think about all sides.”

Tim Wheeler ([email protected])is associate editor of Bay Journal, published by Bay Journal Media, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, to inform the public about issues that affect the Chesapeake Bay. A print edition is published monthly and is distributed free of charge. News, features and commentary are available free online at bayjournal.com. MarylandReporter.com is partnering with the Bay Journal by publishing one of its stories every Friday.

Recent Comments