By Jeremy Cox

Bay Journal

As Maryland officials prepare to take a critical step toward deciding how people will cross the Chesapeake Bay for decades to come, they face growing criticism that the effort is bypassing options that don’t involve building a new multibillion-dollar bridge.

Maryland’s Bay Bridge consists of two adjacent spans between Annapolis and Kent Island: a two-lane bridge constructed in 1952, which serves as the eastbound route, and a three-lane westbound span that opened in 1973.

After more than two years of study, the Maryland Transportation Authority, which operates the 4-mile structures, plans to release a narrowed-down list of possible routes for a potential third span in the coming months.

The $5 million analysis is expected to name a “preferred corridor alternative” by December 2020. Under the most sanguine timeline, a new bridge would still entail a decade or more of planning and construction before it could open, planners say.

As the study nears its next stage, many environmentalists and smart growth advocates are questioning the necessity of a third bridge. They want the state to explore alternatives, such as expanding mass transit or launching a ferry service.

“Given how much money is involved and the time frame for the construction of a new bridge, there needs to be consideration of other options,” said Kimberly Golden Brandt, director of Smart Growth Maryland.

Based on what is publicly known about the study, though, some observers doubt that the state is doing that.

State wants additional capacity, access

Earlier this year, the MDTA released a report on the Purpose and Need for a third Bay crossing in Maryland, stating that the study’s aim is to “consider corridors for providing additional capacity and access across the Chesapeake Bay.” Transportation planners presented a “no-build” option but only to show how congested the existing spans will become by 2040 unless another bridge is built.

An MDTA spokesman declined to comment or make anyone within the department available for an interview for this report.

But at a recent meeting about the crossing study, a top official with the Maryland Department of Transportation threw cold water on suggestions that a ferry, a rail service or buses could alleviate the Bay Bridge’s traffic woes.

No fewer than six studies were conducted between 2000–07 to look at the possibility of connecting the Eastern and Western shores via a ferry service, said Heather Murphy, MDOT’s planning director.

The ferry option that would remove the most traffic from the bridge — a low-speed ferry shuttling between Chesapeake Beach and Cambridge — only managed a cut of 917 vehicles, less than 1% of the peak summer season congestion. Talk of a ferry system needs to be “decoupled from that of a third bridge,” a governor-appointed ferry committee concluded in 2007.

“They didn’t see how that would relieve enough traffic off the Bay Bridge,” Murphy said.

Transit options

A rapid transit bus service or rail system could siphon off about 1,250 vehicles from the bridge’s eastbound lanes during busy summer weekends, she said, citing a 2007 MDTA report. But that would still represent only about a 1% traffic reduction and come with a price tag ranging from $400 million for bus service between Annapolis and Kent Island to nearly $30 billion for a heavy rail system extending from Washington, D.C., to Ocean City.

“You really need a lot more density than we have” to make a mass transit option work economically, Murphy said. “Yeah, you could take some of the traffic of the Bay Bridge and put it on mass transit, but it would be nowhere near the numbers we would need and at a very high cost.”

Murphy was the opening speaker at an April 18 workshop run by the Eastern Shore Land Conservancy at the Chesapeake Bay Beach Club, with sweeping views overlooking the two bridge spans. She isn’t involved in the MDTA crossing study beyond “keep[ing] tabs on it,” she said later.

Lindsey Mendelson, who tracks transportation issues for the Maryland Sierra Club, listened to the presentation with growing dismay. “I was pretty upset by that portion,” she said.

The studies Murphy cited were nearly two decades old in some cases and no longer reflect current traffic patterns or technologies, Mendelson said. The ferry and transit studies, as Mendelson sees it, rely too heavily on how much traffic they can divert off the bridge. What about, for example, the environmental benefits?

“That’s problematic because we’re living in a time when transportation is the No. 1 source of carbon pollution in Maryland and the No. 1 source of climate change emission in the country,” she said.

Heaviest congestion

While bridge traffic is light or moderate during most periods, it is racking up the heaviest congestion scores possible during typical weekday afternoon rush-hours and summer weekends, according to MDTA statistics.

The annual number of vehicles using the bridge has remained steady over the last decade at around 26 million — a phenomenon many planners attribute to the Great Recession.

With one recent analysis projecting 14-mile backups at the Bay Bridge by 2040, though, the public debate has largely shifted away from whether a third span should be built to where it should be built.

The issue has become a flash point on both sides of the Bay.

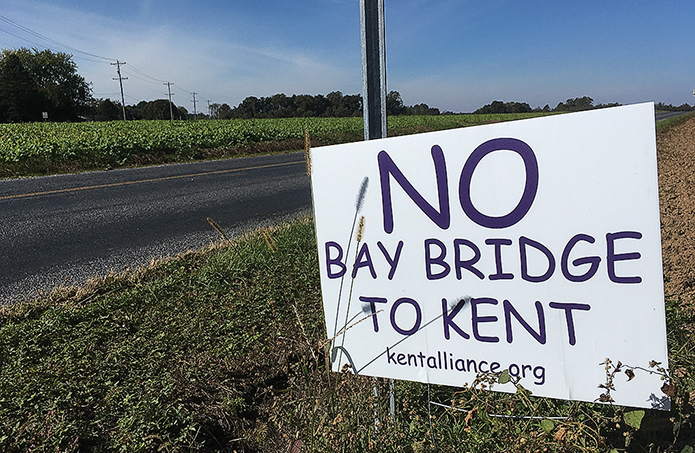

In rural Kent County on the Eastern Shore, “No Bridge” yard signs have begun sprouting outside people’s homes and on the edges of cornfields. Meanwhile, a state senator from the Western Shore’s Anne Arundel County unsuccessfully pushed fellow lawmakers to grant the county veto power over a third span — a power currently given to the nine counties across the Bay.

In February, a map showing 14 potential crossing sites leaked onto social media. It depicted bridges vaulting across the Bay as far north as Harford-Cecil counties and as far south as St. Mary’s-Somerset. The MDTA and Federal Highway Administration created the map but labeled it as “pre-decisional” and “deliberative.”

Fresh cost estimates

The new study is set to project fresh cost estimates for a third bridge, a figure expected to range well into the billions of dollars. What if that money was invested in an alternative to road construction? asks Jay Falstad, executive director of the Queen Anne’s Conservation Association.

“We don’t feel these alternatives have been explored in any meaningful way, and it would just be ridiculous to add a costly third span without exploring these alternatives,” he said.

About 8 million visitors flock to Ocean City during the summer. Falstad suggested staggering their check-in and checkout times to spread out the traffic that currently piles up on the weekends.

During a separate presentation at the conference, Dan Nataf, a pollster at Anne Arundel Community College, said surveys show that at least two-thirds of the county’s residents support expanding the existing bridges or bus service across the Bay. But just 31% would support a higher toll fee to cover the cost.

“I’ll tell you why everything you want to do that costs any money isn’t politically feasible,” he joked.

A bridge won’t just be expensive; it will take years, if not decades, to build. By then, the combined effects of sea level rise and sinking land might have put the approaches to the new bridge underwater, Brandt said.

She hopes that the state’s analysis — and ensuing public debate — includes the impact of a new bridge on the land and communities inland from the Bay’s shoreline.

“There’s so much discussion about the bridge, but what does the bridge connect to?” she asked. “Are you building new roads or expanding existing roads to accommodate the bridge traffic? So, the impacts obviously go far beyond the bridge.”

Critics say a new bridge may be self-defeating. Building new lanes to ease current congestion may encourage more people to drive, creating “induced demand” that quickly snarls traffic once again.

When a panel of transportation experts was asked about induced demand at the conservancy workshop, one replied that it has already happened on the Bay Bridge. In 1985, more than 13 million vehicles were crossing the spans annually, and jams were starting to get on drivers’ nerves.

Steve Cohoon, Queen Anne’s public facilities planner, said Gov. William Donald Shaefer responded with a litany of congestion fixes under the banner “Reach the Beach.” The annual number of vehicles crossing the spans doubled by 2005.

[Editor’s note: The story does not mention the ultimate need to replace the existing bridges because of their age and physical condition. https://marylandreporter.com/2016/09/07/opinion-expanding-the-bay-bridge-is-a-responsible-thing-to-do/]

Ferries are cute, but they do nothing to solve this problem. How can an expensive solution that only displaces 1% of the traffic accomplish anything? It’s a foolish suggestion.

The only two solutions are to increase the supply of roads by building another bridge, or to reduce demand for the roads by increasing the cost to travel to the beach. The Ocean City business community will have a thrombo if anybody considers the second strategy, so we’re left with another bridge.

Rail isn’t feasible, as people are taking too much stuff to the beach. You would need hundreds of train cars on summer weekends, which would just sit around the rest of the time. I hate the damned bridge, which clogs my local roads every Sunday, but there is not another feasible solution.