This is the third part of a Capital News Service special project on the failings of bail reform and the trial system.

By Shruti Bhatt, Angela Roberts and Nora Eckert

Capital News Service

Defendants who reject plea bargains and are convicted when they choose to go to trial for many types of crimes face longer sentences – sometimes substantially longer – than defendants who make a deal, a Capital News Service analysis shows.

For example, the average sentence for defendants who pleaded not guilty but were later convicted of unlawful possession of drugs was seven times longer than those who pleaded guilty, the CNS analysis of Baltimore City court records found. People who pleaded not guilty and went to trial received, on average, sentences of 2 years and 10 months. People who accepted plea bargains were sentenced to about 4 months.

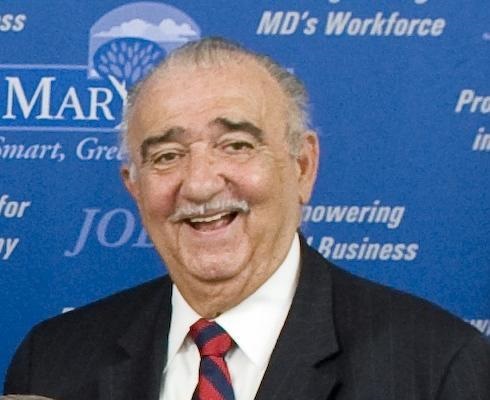

Those pleas save the state the time and cost of a trial. But courts are essentially “punishing people who are exercising a constitutional right, which is the right to trial,” said Steven P. Grossman, professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law.

The gap in sentences was greater for less serious crimes, the CNS analysis showed, but the difference nearly disappeared in cases involving more serious charges.

For example, defendants who were convicted at trial of possessing a gun in connection with a felony received sentences only about 5% longer – 5 years as opposed to 4 years, 10 months – than people who accepted a plea bargain on the same charges, the CNS analysis showed.

‘A system of plea deals’

Grossman, who was a New York City district attorney before he became a professor, says plea bargaining has been common for more than a century. “We are not a system of trials,” he said. “We are a system of plea deals.”

He said judges and courts don’t see plea bargaining as a bad alternative but as “giving people a break for pleading guilty.”

Courts are essentially “punishing people who are exercising a constitutional right, which is the right to trial,” said Grossman. “But, because courts wouldn’t admit to this, they come up with all these absurd reasons for why they give people less time.”

In Maryland and around the country, courts are overwhelmed with cases and more than 90% of cases end in plea bargains instead of trials.

So, why do people plead guilty? Grossman said anyone with the fundamental understanding of human nature would know why.

“They plead guilty because they want less time, which is what you would do or what I would do. The lawyers tell them they will get less time,” he said. “The only way plea bargaining works is if we give defendants less time if they plead guilty and more time if they go to trial.”

In a 2018 Nevada Law Journal article called “Making the Evil Less Necessary and the Necessary Less Evil: Towards a More Honest and Robust System of Plea Bargaining,” Grossman wrote that the trial penalty presents challenges in at least two kinds of cases.

The first, Grossman said, comes in cases where defendants were given “significantly harsher penalties after trial than they were offered in a plea bargain.” And the second arises in cases in which the “defendant who was convicted after a trial receives greater sentence than his co-defendants with similar or worse criminal records who were equal or more primary participants.”

Allowing judges to be more involved

Grossman suggested judges should be more involved in the process by letting defendants know the range of sentences likely if convicted at trial.

Judges are wary of offering such information, Grossman said, for fear of appearing to be coercing a defendant into take a plea deal. Such cases likely would be reversed on appeal.

But Grossman said judges could still help the defendant understand what his options are without being coercive.

If the defense attorney and defendant ask a judge what the range of sentences would be if found guilty, Grossman said the judge shouldn’t withhold that information.

“These defendants are making the most important decision of their lives, about whether they should plead guilty or not,” Grossman said. “They’re being told what they’re going to get if they plead guilty. But they’re not being told what they get if they go to trial. So they make the decision with half a basketful of information that they need to make an educated decision.”

Recent Comments