By Jeremy Cox

Bay Journal

A half-submerged tree trunk bobbed in the waters of the Chesapeake Bay.

From his perch several hundred feet away aboard a small barge, John Gallagher began giving orders to his crew. Not much needed to be said. By now, the actions of the other three men had become almost automatic.

“Here’s a good example of what the debris looks like in here,” said Gallagher, head of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ hydrographic operations. “This is right off the channel.”

Chris Ruark steered the boat close enough for Aaron Nelson and Matt O’Neal, both clad in hard hats and orange life jackets, to fit a pair of large tongs around the waterlogged tree. Then, they reeled it into the boat’s hull using a crane mounted on the side of the vessel.

Then it was on to the next navigational hazard. And the next.

So it went for Gallagher’s small enterprise as it chipped away at a big assignment: making the Bay safe for boating after a summer of epic rains flushed untold amounts of debris into its waters.

140,000 pounds of debris

As of Sept. 27, DNR crews had removed 140,680 pounds of storm-related debris from navigable waters in the Bay. But the work was far from done. Gallagher said he expects the cleanup to continue, after a winter intermission, well into 2019.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also has pitched in, but its boats largely concentrate on the federally maintained channels immediately around the Port of Baltimore and District of Columbia. That leaves the DNR with the balance of the Bay’s navigable Maryland waters as well as many of its many tributaries.

This year is already the wettest ever recorded in Maryland.

When rain turned heavy this year, especially in July, it sent torrents of stormwater across the land into ditches and streams, down rivers and eventually into the Bay itself.

Most media reports about the long-range impacts have focused on the tons of nutrients and sediment flushed into the Chesapeake. The waters at the mouths of several rivers, including the Susquehanna and Potomac, temporarily turned the color of chocolate milk. Scientists worried that the sediment would block sunlight from reaching underwater grass beds and that nutrients would fuel alga blooms that trigger oxygen-starved “dead zones.”

But the rushing water also carried large pieces of debris, such as fallen trees and everyday garbage. While less troubling to the Bay’s health, the flotsam represented a major headache for boaters, shoreline communities and waterfront homeowners.

People like Archie Hall.

Debris in Pasadena

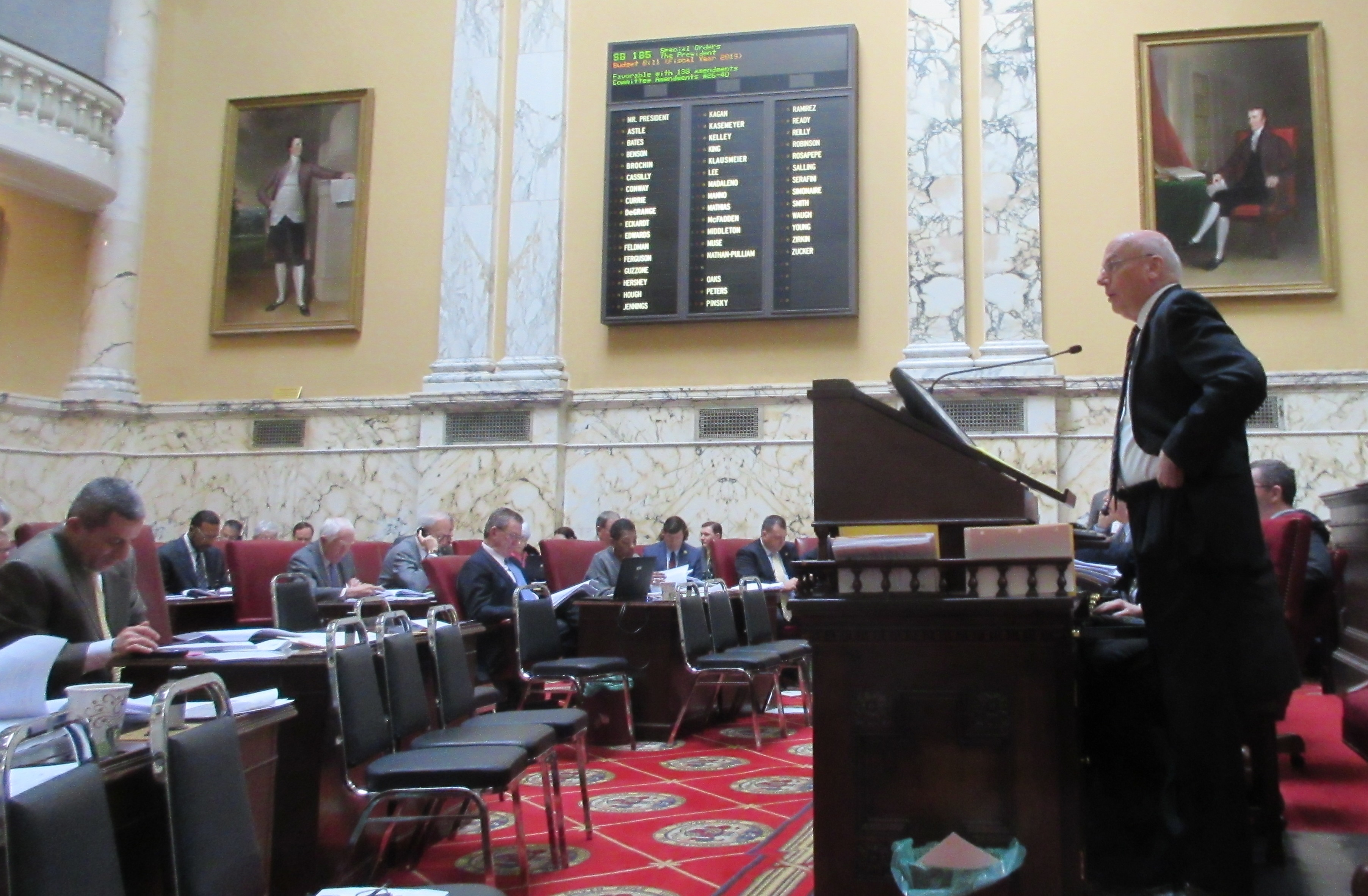

Matt O’Neal holds onto a waterlogged tree while Aaron Nelson, a hydrographic engineering associate with the MD DNR, cuts into a tree found floating in the Bay near Pasadena. Bay Journal photo by Jeremy Cox.

Hall, 82, has lived in the Bayside Beach subdivision in Pasadena for 30 years. He has never seen as much debris in the Bay as he did this year, he said. By late October, when Gallagher and his crew tied up at his dock, most of it had been picked up by neighbors or floated away.

“It was four times this bad, floating in and out,” Hall said. “What’s left is stuck on a rock or floating on a pier.”

Debris removal involves some triage, Gallagher said. His top priority is snagging anything that poses a threat to boat safety in channels, the main thoroughfares for watercraft. Then comes anything outside the channels that could float back that way with the wind and tide.

In normal times, the hydrographic operation busies itself with placing buoys, removing abandoned boats and piloting the state’s three icebreaker boats in the winter. The last few months have not been normal times, though.

Gallagher said his crews removed 10 boatloads of debris alone from Lake Ogleton, an anchorage off the Severn River. They also spent considerable time in the Middle and Chester rivers.

Mostly tree limbs and trunks

The majority of the material has consisted of tree limbs and trunks. But there have been oddities, including an industrial chlorine tank and a giant tire from an excavator, Gallagher said.

The tire has been repurposed as a piece of workout equipment at a gym, but there is no recycling for the rest of the debris. The trees can’t be ground into mulch because they sometimes contain metal shrapnel, which damages the state’s tree chippers.

Usually, the DNR boats haul their quarry to Kent Island, where it is loaded onto dump trucks and taken to a landfill in Ridgely. A boat loaded with 5,000 pounds of debris can’t go very fast or else it risks getting swamped. So to save time during Western Shore cleanup jaunts, the Army Corps has begun making available its drop-off site at Fort McHenry.

Gallagher said that once a piece of debris has lodged itself safely on land, it’s out of his division’s hands. But he immediately decided that the once-towering tree trunk in front of Hall’s home had to go. It was wedged onto a stone jetty but still partially underwater — free perhaps to catch a ride on a future high tide.

In a flurry of sawdust and flying water, Nelson used a chainsaw to cut the trunk into three pieces. O’Neal moved the levers of a remote control to lift the chunks into the 36-foot aluminum boat, dubbed the R.P. Gaudette.

Just as the last piece dropped with a thud, something went wrong. A few puffs of smoke boiled up from the crane’s engine. After a few minutes of tinkering, the men decided they would have to retrieve a replacement part from the Army Corps.

As their boat slowly gathered speed out in the open water, the sunlight sparkled on the surface, showing no obstacles in their path.

Recent Comments