By Timothy B. Wheeler

Bay Journal

A waterman tonged for oysters nearby as the diesel-powered Miss Kay chugged out from Oxford to join him in searching for shellfish in Maryland’s Tred Avon River.

The first drag of the vessel’s dredge across the bottom came up brimming with shells, which the crew quickly began picking through.

These oysters weren’t destined for a raw bar, though, or a shucking house — the entire catch was part of an annual oyster “bed check” by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

In the course of the morning, 30 bivalves would be kept as a sacrifice to science back on shore. The rest, after being counted, measured and recorded, would go back in the water.

Every year since 1939, Maryland has surveyed its portion of the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries to see how the oysters were doing. Though no longer the mainstay they once were, oysters are still a pillar of the region’s fishing industry and a vital cog in the Bay ecosystem.

What they look for

Biologists and fishery managers use the information gleaned from the survey to see how successfully oysters reproduced that year, how many died and — for the last several decades — how widely and seriously they may be infected with a pair of potentially fatal diseases.

The survey also yields a “biomass index,” a general indicator of the oyster population’s status that combines the number and weight of bivalves sampled from a fixed batch of reefs.

Last fall, the DNR survey crew collected 327 samples from 272 oyster bars, including some in Maryland’s extensive network of oyster sanctuaries and others in bars that have been worked by watermen for centuries.

This fall, though slowed by blustery weather, the crew aboard the Miss Kay have been making the rounds again.

On a chilly but fair November morning, four of the crew crowded around a culling tray in the middle of the 48-foot vessel. Their gloved hands quickly sorted through the muddy half-bushel of shells dumped in their midst, examining each find briefly.

DNR biologist Amy Larimer stood by, clipboard in hand, recording their observations as they called them out in rapid verbal shorthand.

“Ten markets…One small…Mud crab — did you get mud crab? … Market box, old…Five markets… Small…Small…Small box, old…Small…Ten markets…Ten markets.”

Larimer logged the number of market-size oysters, 3 inches or larger, and the number too small to be legally kept. She also tallied how many “boxes” or empty oyster shells they saw, broken down by how recently the animal inside appeared to have died. And she noted if her crewmates spied any barnacles, mud crabs or other creatures lurking among the oysters.

Occasionally, a culler called out “spat,” the term for a recently hatched oyster larva that has attached itself to something hard, usually the shell of another oyster. Those spat, sometimes not much bigger than a dark speck, will grow over the next few years to market size — if they survive predators, disease and pollution.

DNR survey crew members use this tool to tell quickly if oysters have grown to market size of three inches across. (Timothy B. Wheeler)

Surveys indicate trends

By the time the survey data are parsed and published in a report, sometime next spring or summer, this year’s commercial harvest season for wild oysters will be over — it ends March 31. But the survey gives a sense of where the oyster population is headed in the next few years. Past surveys provide a historical record against which to measure current conditions.

“I think it’s a good indicator of trends,” said Mitch Tarnowski, the survey leader, who’s been on the annual cruises since 1999. “It’s obvious if you’ve had a good spat set or not.” And, he added, “It’s pretty obvious if you’re having a mortality event.”

Four years ago, the DNR survey yielded the highest biomass tally in more than two decades, reflecting a rebound from the severe bout of the diseases Dermo and MSX that struck a decade earlier. And it mirrored a surge in the wild commercial harvest, as Maryland watermen landed 416,000 bushels in the 2013–2014 season — their best haul in 15 years.

The renewed bounty brought watermen who had left oystering back into the fishery, doubling the number reporting harvest.

But the 2016 fall survey report found “cause for concern.” While the number of spat seen on sampled reefs was well above the long-term median — indicating fair but not great reproduction — the survey found MSX and Dermo on the rise, possibly the result of increasing salinity in the Bay’s waters, which encourages their spread. There was also an uptick in the number of dead oysters showing up in the dredged samples.

Moreover, the biomass index continued to slide from its peak, largely because of decreased reproduction that’s occurred in Maryland waters.

Oysters grow from spat to market size in about three years, and the harvest surge a few years ago came on the heels of a bountiful spat set in 2010. Another good spat set in 2012 helped keep harvests at nearly 400,000 bushels for another couple of years.

Last season’s harvest, though, bore out the concern expressed in the fall 2016 survey report, as disease took its toll amid smaller crops of new oysters reaching market size. Watermen landed just 224,609 bushels, a 42% drop from the previous year.

DNR biologist Robert Bussell and Ellen Woytowitz of the U.S. Geological Survey measure oysters and sort them in buckets by size. (Timothy B. Wheeler)

Dead oysters, baby oysters

The DNR crew wasn’t expecting to finish this year’s survey until the end of November or early December, and the data haven’t been crunched yet. But Tarnowski said they haven’t seen an unusual number of dead oysters so far.

That’s something of a relief, because salinity levels were higher than normal in the Bay again this year, at least through midsummer in much of the Bay, which could have bred more disease. Even so, Tarnowski said, “Mortalities haven’t been extraordinary.”

On the other hand, higher salinity tends to boost oyster reproduction and that doesn’t seem to have occurred, either. Tarnowski said that the number of spat seen in the survey to that point “hasn’t been exceptional — it’s been average.”

“You’d expect to see a much better spat set,” he said.

But while salinity is necessary, he added, it’s clearly not enough by itself. The reproductive process of oysters remains something of a mystery. Despite decades of studies, scientists still don’t know all of the factors that determine how many oyster larvae are generated and how many, after swimming around in the water for two to three weeks, succeed in settling to the bottom and attaching themselves to a hard surface on which they can survive and grow.

“It’s been a nutty year,” suggested Mark Homer, veteran research statistician on the survey crew.

In addition to giving watermen and fishery managers a sense of how the oyster population is doing, Maryland’s fall survey has shed light on recent controversies over the value of oyster sanctuaries in that state.

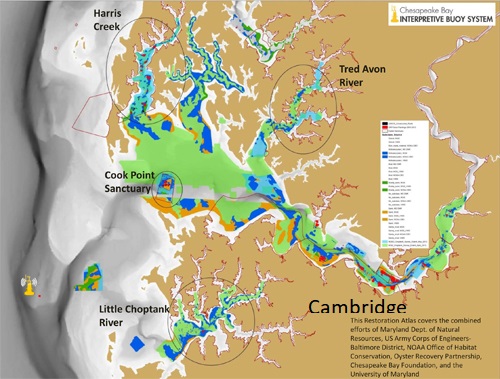

Seven years ago, the state included a large swath of the Tred Avon in its expansion of oyster sanctuaries, and a large, federally funded project began in 2015.

The project has been a bone of contention with watermen, whose protests to the Hogan administration succeeded in delaying the construction of the reefs for most of last year. They contended that building reefs and planting hatchery-spawned oysters in sanctuaries is a waste of taxpayers’ money because oysters left on reefs not worked over during a harvest would die of disease or be smothered by sediment.

Last year’s survey, though far from conclusive, did not support those claims. The report said that all of the major sanctuaries appeared to be holding their own, while the areas closed to harvest in the Manokin and Little Choptank rivers “averaged among the highest regional spat sets in the bay.”

Harris Creek restoration

Maryland’s only completed oyster restoration project is in Harris Creek, not far from the Tred Avon, and has also been criticized by some watermen. They argue that, despite spending more than $26 million on constructing reefs and planting close to a billion hatchery-spawned oysters, reproduction in Harris Creek doesn’t come close to that on the reefs in neighboring Broad Creek, where watermen harvest oysters every year.

Past surveys show that Broad Creek has almost always outshone Harris in terms of spat counts, for reasons scientists can’t explain. But the 2016 survey report noted that a reef called Rabbit Island in the Harris Creek sanctuary had the highest density of spat of any place sampled in the vicinity. Overall, the report added, the Harris Creek sanctuary had a similar average spat set to its neighbor, Broad Creek.

The DNR’s oyster surveys have also helped to document the impact of using materials other than oyster shell for restoring reefs. Oyster shells have been in short supply and too expensive for use in large restoration projects, so state and federal agencies have used granite, clam shells and even fossil oyster shells dug from a quarry in Florida.

Fossil shells were used to rebuild reefs in the Little Choptank River, a project that some watermen contended was ineffective and smothering the bottom with sediment. The 2016 survey, though, found that the rebuilt reef had the highest spat count of all the reefs checked.

Bay Journal is published by Bay Journal Media, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, to inform the public about issues that affect the Chesapeake Bay. A print edition is published monthly and is distributed free of charge. News, features and commentary are available free online at bayjournal.com. MarylandReporter.com, also a 501(c)(3) nonprofit news organization, is partnering with the Bay Journal by publishing one of its articles every Friday.

Recent Comments