Bon Secours Hospital occupies a block amid brick rowhouses in West Baltimore. Kaiser Health News photo courtesy Doug Kapustin.

By Rachel Greenwald and Rachel Bluth

Capital News Service

Bon Secours Hospital, which sits amid blocks of West Baltimore rowhouses, lacks the prestige of the giant Johns Hopkins and University of Maryland hospitals, with their renowned teaching staffs and research facilities. It lacks the sprawling glass pavilions of southwest Baltimore’s St. Agnes Hospital, which looks like a suburban medical center.

It’s been a fixture in the neighborhood since 1919, when it was opened by an order of nuns who served middle-class patients from all across the city.

But today, few patients are affluent. The hospital, outpatient services and wellness center that compose the system primarily serve neighborhoods including Sandtown-Winchester and Harlem Park, predominantly black neighborhoods made famous in pop culture by TV shows like HBO’s “The Wire.” The death of Freddie Gray, who died after an injury in police custody, brought even more unhappy attention to the area last spring.

A killer reputation

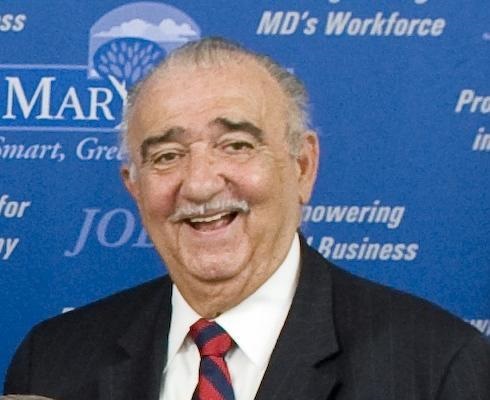

Improving Bon Secours Baltimore Health System’s reputation along with the health of the community requires collaboration “with our other partners here in West Baltimore,” says CEO Dr. Samuel Ross. Kaiser Health News photo courtesy Doug Kapustin.

Dr. Samuel Ross had been CEO of Bon Secours Health System for three months when he went to a dinner party in 2006 and first heard the name some Baltimoreans have long used for his hospital.

They called it Bon Se-killer.

Ross says the reputation is based partially on urban myth, spread largely by people who’ve never walked through the hospital’s doors. Bon Secours’ mortality data don’t support the disturbing label, though it has endured in the community.

But Joyce Smith, who has been an activist in West Baltimore for 30 years, says the nickname reflects larger problems with medical services in her neighborhood.

Patients here, Smith says, tend to be sicker.

“The people who go to Bon Secours, they are already at their last leg when they get there,” says Smith, president of Operation ReachOut Southwest. Many don’t have a primary care doctor. “There’s no prevention. There’s no maintenance.”

Residents of these neighborhoods are 35 percent more likely to die from heart disease than the city as a whole, according to an assessment of community health needs published by Bon Secours in 2012. Life expectancy in Baltimore City is 73.5 years, according to Census data, but in parts of West Baltimore it is 66.

Dr. Marcia Cort worked at University of Maryland Medical Center downtown and later in her career at Bon Secours, a mile and a half away. She observed differences in the condition of people who arrived for medical care.

“I realized that in that very short distance between the University of Maryland and Bon Secours Hospital that the patients at Bon Secours are pretty sick,” says Cort, now chief medical officer at Total Health Care, which operates clinics for low-income people in West Baltimore.

“They’re actually sicker than the patients that I was seeing at the University of Maryland hospital. Just separated by that very short distance.” People were being diagnosed with diseases at younger ages and showing up for care later in their illnesses, she says.

Data doesn’t show high mortality rate

When adjusted for the severity of patients’ illnesses, Bon Secours’ mortality rates are little different from state averages for all hospitals, according to data collected by the Medicare program for seniors and posted by whynotthebest.org. That site compiles government data to track hospital performance and improvement.

In recent years, Bon Secours has reduced the rate at which patients contract potentially deadly in-hospital infections, such as those of the lungs, blood or urinary tract, state data show.

But Bon Secours has fallen short in several important quality measures. Patients undergoing surgery were less likely than those at the average Baltimore hospital to get clinically recommended treatments to protect them from infections and blood clots, according an analysis of the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. For instance, just 88 percent of Bon Secours’ patients were given an antibiotic within an hour before surgery to prevent infections, the lowest rate among Baltimore hospitals, records show.

In response, a Bon Secours spokeswoman notes that data was from 2014 and that the hospital has improved its processes, tools and monitoring to achieve better patient outcomes. “Our goal is to deliver the right care, at the right time, and in the most effective manner to all patients,” she says.

Primary care center planned

Now, in an effort to improve the health of its neighbors and keep them out of the hospital, Bon Secours has bought a neighborhood church and is spending $7 million as it renovates the building to create a center for primary care. Providing basic health care for the community should help decrease rates of disease and eventually benefit the hospital’s bottom line as Maryland revamps its approach to hospital payments.

The Bon Secours Health System’s operating revenue in 2014 was $122.4 million. It has nearly 800 employees, including 165 doctors, and two years ago reported 4,660 admissions to its hospital and 104,000 outpatient visits.

In 2014, Maryland changed its Medicaid reimbursement system. Instead of reimbursing individual procedures, the state awards hospitals a set amount of funding for the year. No matter how many patients the hospitals see or how many tests they run, each hospital has a fixed budget to cover its costs. Hospitals keep any excess funds.

The system is meant to be an incentive to provide primary care outside of the hospital so people are less sick when they walk through the door.

Ross and Smith, whose organizations partnered in 1997 to work on neighborhood problems, want to expand the definition of what constitutes a health problem.

It’s not just disease, residents tell Smith. “The community said, ‘Our problems are rats and trash.'”

Ross knows the problems people have with his hospital, whether real or imagined, will take more time to resolve. No new ad campaign will scrub years of “Bon Se-killer” away. Ross says only hard work and good results will do that.

But, the lack of trust goes beyond his own hospital.

“I grew up in a small town in Texas, and I can tell you there’s just a basic distrust of white people,” says Ross, who is black. “And it was a lot of fear of: If I go into this environment and if I don’t come out, then it’s just all a mystery.

“The distrust for health care institutions was as much as the distrust for a lot of other situations — police and others.”

Gaining back the trust

While Ross hopes to gain residents’ confidence, Smith says the hospital must in turn begin to trust the residents. She says it is important for the staff at Bon Secours to believe the people do care about health and want to be part of the change. And she wants the community and Bon Secours to make sure resources are spent on what people really need.

Smith sees a model where health care providers can refer their patients to specialized community-organized workshops.

Ross also embraces collaboration, especially in maximizing primary health care. He envisions turning church basements into places where residents get their blood pressure checked.

“There’s an African proverb: So you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together. And we have to go together with our other partners here in West Baltimore,” Ross says. “We’re going to keep hope alive.”

Residents who are irresponsible with (or ignorant of) their own health management, and who don’t trust white people, doctors, or hospitals would be expected to be sicker and die younger. Average life expectancy of 66 years, on the other hand, seems to run counter to the story’s anecdotal evidence. So I’m skeptical the life-expectancy statistic and the story’s anecdotes can both be true simultaneously.