By Bethany Hooper and Matt Beinart

Capital News Service

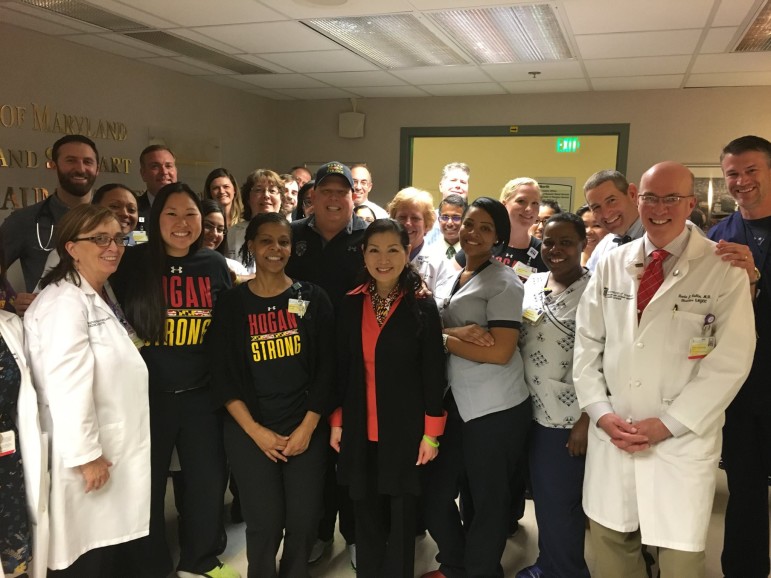

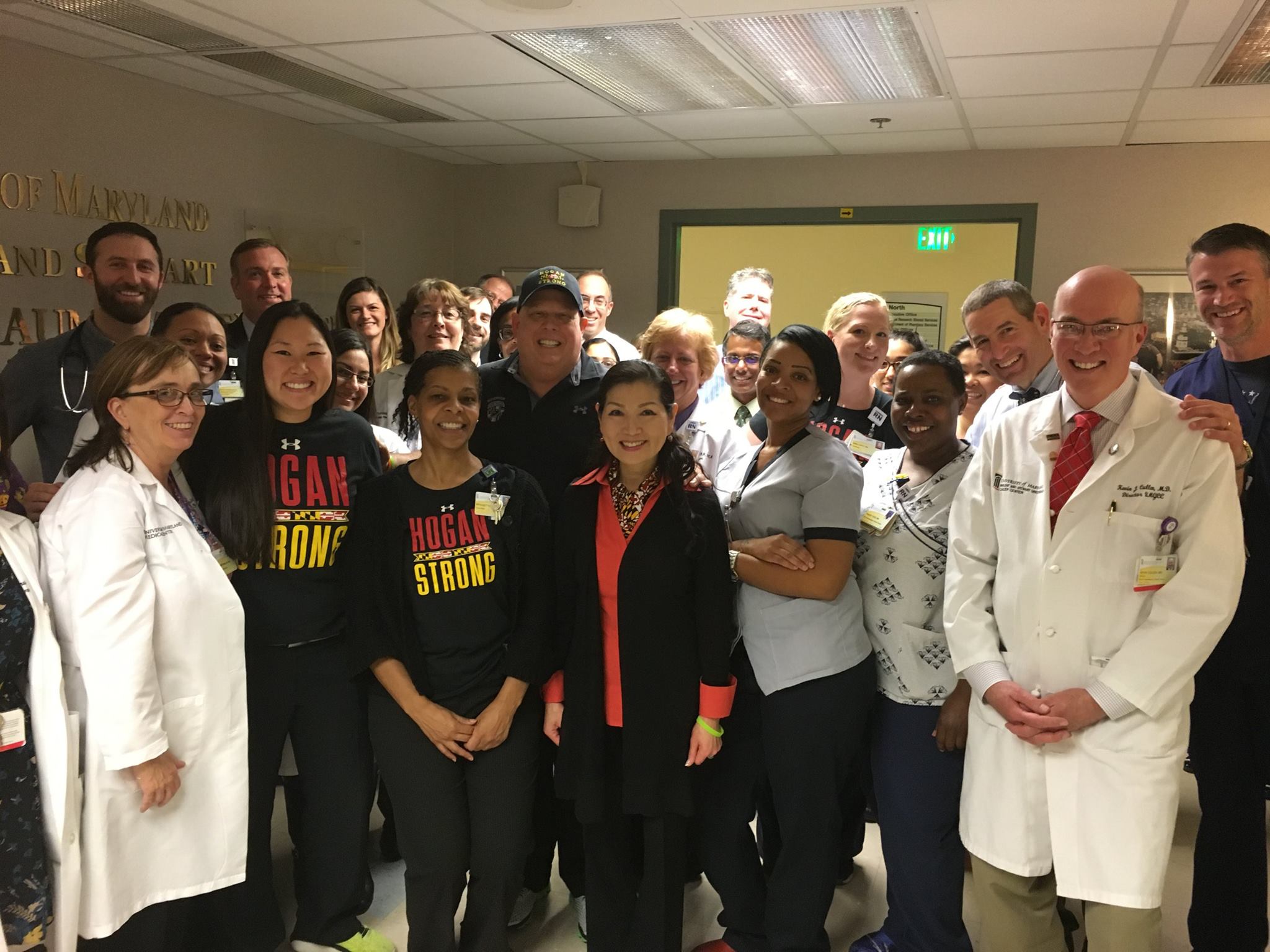

Gov. Larry Hogan with staff at Greenebaum Cancer Center. Dr. Kevin Cullen in white coat is at far right. From Larry Hogan’s Facebook page

Kevin Cullen’s mom passed away from cancer after his high school graduation. She left two things behind: an engraved stethoscope and a son on a mission.

Now a doctor and director of the Marlene and Stewart Greenebaum Cancer Center at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, Cullen is working with state programs to fund cancer research.

Much of this funding comes from the Master Settlement Agreement of 1998, which allocated restitution money paid by the tobacco companies across 46 states in an effort to combat tobacco-related addiction and disease.

In 2015, Maryland spent 33% of its allocated cancer prevention and treatment money at the University of Maryland Medical Center and Johns Hopkins University, according to the Cigarette Restitution Fund, a division of the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Current restitution funding has provided benefits for both cancer prevention and tobacco-use prevention in the state, according to Bonita Pennino, Maryland and District of Columbia government relations director for the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network.

Maryland cancer rates dropping

“We are … finding that our cancer rates are dropping,” Pennino said. “We were once rated second in the most cancers in the nation, and now we are closer to 23. We are making progress all the way around and the money from the Master Settlement has helped to do that.”

Some of this money is then channeled into the University of Maryland’s Baltimore City Cancer Center Program to provide resources for the underinsured.

“We think it’s important that if you’re doing a screening program, if you diagnose someone with breast cancer, you get to have the wherewithal to treat them,” Cullen said.

However, resources and research through the University of Maryland Medical Center and Johns Hopkins benefit all who seek treatment at these institutions, according to Cullen.

A few of these patients include Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan and the cancer center’s namesake, Marlene Greenebaum, a Baltimore community leader and investor in the medical center.

As a result of cancer treatment and prevention funding, many specialists across the nation turn to Maryland institutions to conduct research, according to Pennino.

Local cancer research helps economic growth

An annual report from Johns Hopkins urges the Maryland legislature to continue to support research through the Cigarette Restitution Fund, citing state economic growth as one benefit.

“The emphasis with this particular report is…money was getting cut from previous years, and…(hospitals) would be losing some stellar researchers that specifically moved to Maryland to do some cancer research,” Pennino said.

Jon Schachter, director of state communications from the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, argues that, while treatment spending has been successful, it is cheaper to prioritize tobacco-use prevention.

“The state spends over a billion dollars each year on health care costs because of tobacco usage,” Schachter said. “If we curtail tobacco usage and cut smoking rates among kids and adults, you are going to start saving a lot of money. It’s a lot cheaper than dealing with the symptoms…”

Some of these screenings do not stop at treating the symptoms, according to Donna Gugel, director for the Cigarette Restitution Fund. Some Maryland programs, such as colorectal screenings, provide both treatment and prevention, Gugel said.

“If you go in and do a colonoscopy and you find a polyp and remove the polyp, you are actually preventing a cancer from developing,” Gugel said.

Partial funding through the Cigarette Restitution Fund allowed researcher Angela Brodie to develop the drug aromatase inhibitors at the Cancer Center that helped cure Greenebaum of cancer, according to Cullen. It’s a clear example of how state funds from the settlement agreement produced treatment possibilities that can save lives.

Aromatase inhibitors is a drug that prohibits new breast cancer cells from forming by blocking estrogen production in the body.

“It’s had a significant impact on cancers that are also very important,” Cullen said. “So I think we have taken the (restitution) investment and developed an infrastructure for research and treatment that benefits patients with cancer, no matter what type of cancer they have.

Recent Comments