Republished with permission of the Maryland Public Policy Institute. Photos and charts from the Maryland Transit Administration.

By Nick Zaiac

Maryland Public Policy Institute

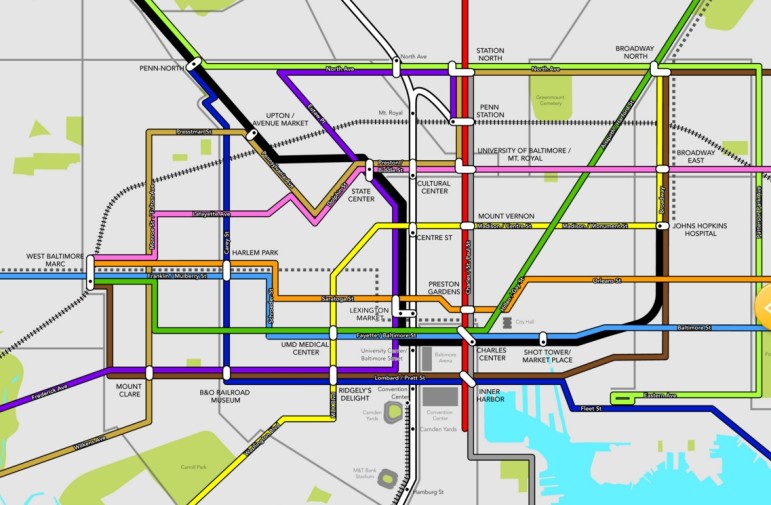

In late October, Gov. Larry Hogan announced BaltimoreLink, the most dramatic reworking of Baltimore’s mass transit in years. The $135 million plan seeks to improve mass transit in Baltimore in the wake of the canceled Red Line project.

This announcement is surprising to many, as the funding source for the new improvements is unclear, and the first improvements began Oct. 26, just four days after the program was unveiled. Despite this uncertainty, the plan’s bus-centric nature is far sounder than the Red Line’s costly rail-based model. We review and analyze each component of the program, and for comparison, we take a look at some programs that have worked in other cities and states.

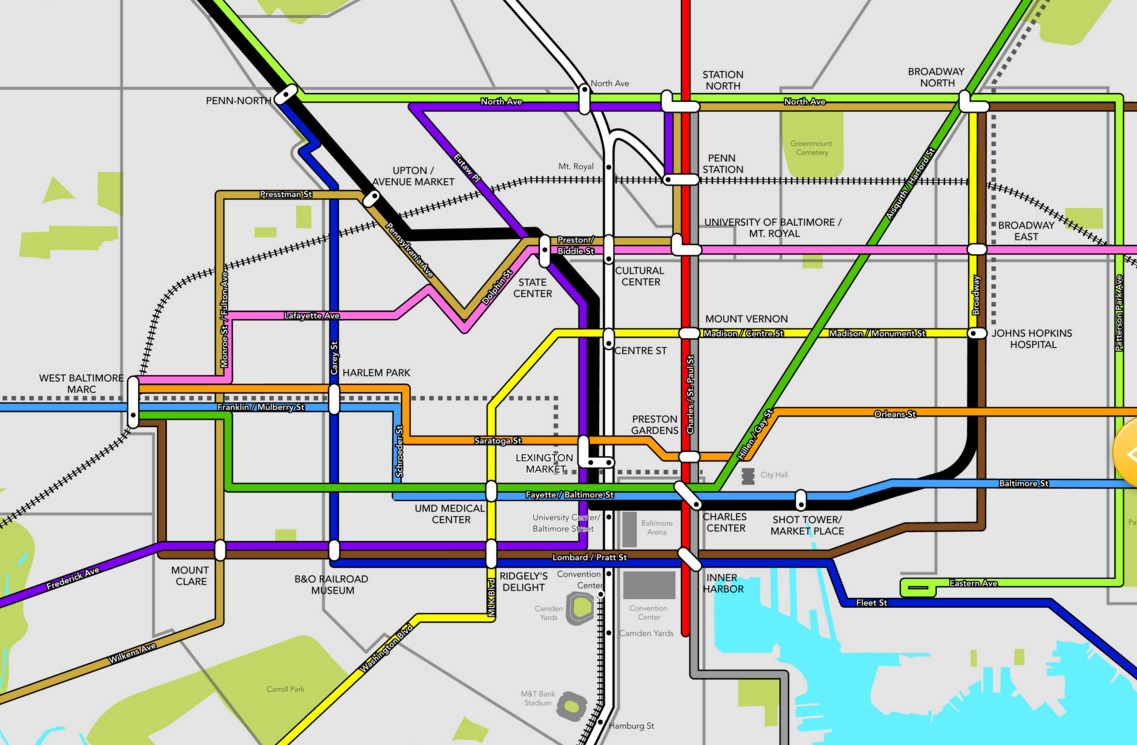

The high-frequency Baltimore CityLink bus is a true backbone of the transit system.

Academics have argued for decades that, when designed correctly, high-frequency bus service is the most economically efficient form of mass transit, especially in smaller cities where density downtown is limited and jobs are distributed across the region.

This was the argument of Alan Altshuler, the former head of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, in his 1981 book The Urban Transportation System, and has been accepted by urban planners nationwide, despite the frequent desire for higher-cost rail service. Baltimore fits this mold well, and is better suited to a larger network of bus lines than a few costly rail lines. While rail is seen as higher quality, that quality comes at the cost of both the frequency of service and coverage of the service area.

The key, then, is getting bus service right, and that’s harder than one might think. While CityLink isn’t quite a true Bus Rapid Transit system, it comes fairly close. The service will have 10-minute on-peak and 15-minute off-peak service, and will be laid out in an understandable format, with a map which looks closer to typical rail service. It will provide a one-transfer link between each bus line and the city’s current rail-based system.

This structure should correct many of the typical complaints about bus service, including the problem of buses not showing up (or being extremely late), which makes planning one’s transportation around transit service difficult.

Express BusLink’s suburb-to-suburb service will reflect real commuting patterns.

This new service will connect major suburban job centers with the CityLink system and major suburbs. Today, most jobs in the region are not in the city center, and transit service should reflect that fact. Express BusLink does that, and also provides service to suburban transit hubs, making these job centers accessible with minimal transfers to commuters across the region.

Moreover, because the service will be limited-stop, it should be more reliable than typical bus lines. Suburban transit, where it typically exists, is run infrequently and unreliably, with just a few trips per day. That leads to low use rates, which makes such transit expensive to provide. If transit is to be provided in the suburbs, it should be frequent, bi-directional, and limited-stop—qualities inherent in this plan.

LocalLink is the Houston-esque redesign that needed to happen.

Local bus routes in cities are typically just ‘routes’ rather than any kind of unified system. Service is often planned to appease activist political constituencies rather than provide reliable, useful service for everyday commuters and travelers. It makes sense that service designed in this fashion would not be particularly efficient or easy to use.

This year, Houston launched a system redesigned from scratch, and it’s proven generally successful. Baltimore’s LocalLink mirrors this plan, which will ensure each and every bus line makes sense, and that the system is easy to understand for locals and visitors alike.

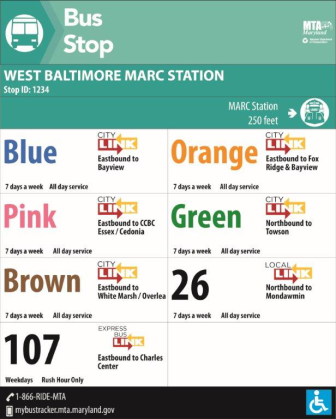

Clearer signage is the simplest, most obvious improvement to the system.

Clearer signage is the simplest, most obvious improvement to the system.

This is a no-brainer. If you’re going to provide transit service, it should be clear where it goes, how often, and where you should stand to get a ride. Location-specific information is a plus, and helps people navigate necessarily-complex urban transit networks.

For example, navigating London’s web of bus networks would not have been possible without the clear, uniform signage and location-specific notes that are placed at each bus stop. For those who lack the luxury of using smartphone-based maps, clear signage is especially important, and it’s a low-cost way to make navigating Baltimore far easier.

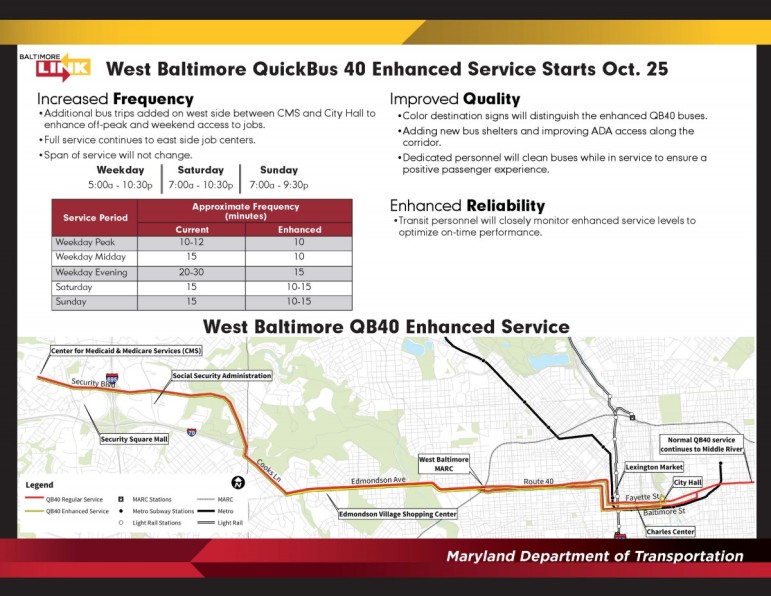

West Baltimore’s QuickBus 40 improvements should have been part of CityLink.

This service has already started. The plan calls for more bus shelters, and will see buses cleaned by staff throughout the day. Of all parts of the plan, this seems like more of a political sweetener than anything else. It’s the one part of the plan that won’t be rebranded, and began just days after the initial announcement. While West Baltimore may need more service, it would have been better to incorporate the bus as a line in the CityLink system.

This service has already started. The plan calls for more bus shelters, and will see buses cleaned by staff throughout the day. Of all parts of the plan, this seems like more of a political sweetener than anything else. It’s the one part of the plan that won’t be rebranded, and began just days after the initial announcement. While West Baltimore may need more service, it would have been better to incorporate the bus as a line in the CityLink system.

Transitways for bus lanes are controversial, but key to the system.

The shortest part of the fact sheet will be among the most important, and the most controversial. For CityLink to truly succeed, dedicated bus corridors with dedicated bus lanes will be necessary along some downtown streets. Downtown traffic is typically the biggest cause of the delays that make most current bus systems unreliable.

But the transitways will not be easy or uncontroversial to implement. This will mean taking lanes from auto drivers downtown, which will inevitably make some angry, as traffic will certainly increase in come corridors. The specifics remain to be seen, but it will be important for MDOT to carefully select which streets to convert into transitways.

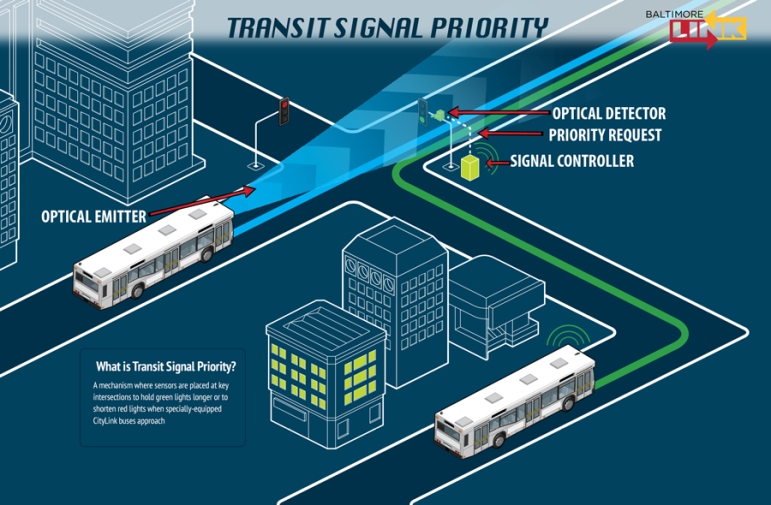

Transit signal priority technology brings more reliable bus service.

Transit signal priority technology brings more reliable bus service.

Transit signal priority, like improved signage, is a generally good idea for any bus-centric system. This will help bring reliability to the CityLink and LocalLink systems, making it easier for transit-dependent riders to plan trips. It’s a common-sense, fairly low-cost reform that is slowly being picked up by cities worldwide. If Baltimore is to have a world-class bus system, signal priority will be a key part of it.

Transit hubs are likely expensive, but important to the system.

The plan includes a total of six transit hubs, all at major transfer stations, generally outside of downtown (the proposed Lexington Market hub is the notable exception). If done right, they will prove to be a key component to the city’s transit network, but oversight will be key. Montgomery County’s Silver Spring Transit Center is one of the nation’s most notable infrastructure boondoggles. For Baltimore to avoid a similar mess, the hubs will have to be kept simple and utilitarian. MTA hints that they will be, but if they are not, costs could spiral, and could prove to be a substantial burden to taxpayers.

Connections to Central Maryland will not necessarily meet a need for additional service.

The plan touts improved Commuter Bus service to a number of car-centric suburbs, ranging from Fort Meade to Arundel Mills. This service could be valuable to certain commuters, but could also prove to be an expensive bonus service for areas where almost all workers drive to their jobs.

It’s probably best to reserve judgment until it is clear precisely which routes MTA seeks to run—decisions which should not be too far in the future, as service is set to begin in July 2016.

Despite this, running an entire bus line for a single employer is probably unwise. Many employers offer employee shuttle service, and if there is demand for the service, taxpayers should not be footing the bill for firms to get their employees to work.

New Service to Annapolis, Aberdeen, and Columbia is a luxury Marylanders may want.

There is a far better public policy reason for running intercity bus service than running service to individual employers. Adding reverse-commute service to Annapolis and Aberdeen could certainly open job possibilities for Baltimore residents. Enhanced bus service to Columbia is a good idea, as service already exists, and making it more reliable could integrate the region to the west of the city more thoroughly. Plus, Columbia is geographically closer than either Annapolis or Aberdeen, making service cheaper and more likely to be demanded by prospective riders.

Enhanced Light RailLink Service would remove an inconvenience for some.

While the plan generally focuses on bus service enhancements, a couple improvements to the city’s light rail system will be rebranded as Light RailLink. Safety improvements will be made at some downtown intersections. More notably, Sunday light rail service will expand from 11 a.m. – 7 p.m. to 6 a.m. – midnight. This service expansion will likely result in poor ridership, but some who commute to downtown jobs will find it useful. Once implemented, officials should carefully watch ridership figures, and cut service if too few people end up using the system during newly-expanded hours.

Last-mile investments are a handout to cyclists.

Last-mile investments are a handout to cyclists.

The plan proposes adding bike-share docks at some rail stations downtown, and new bike racks at each MARC/Light RailLink/Metro SubwayLink station. On top of this, every MARC Penn Line train running on weekends will have a Bike Car attached, allowing cyclists to move between Washington and Baltimore, bike in tow. The plan also expands Charm City Circulator funding.

All together, these improvements make cycling in the city easier, although the actual benefits citywide will be dubious. Use rates of Bike Car service are unclear, but expansion was likely in the works prior to the plan’s announcement, as this service began on Oct. 31.

Enhanced security and cleanliness brings extra quality, but at what cost?

The plan will see more police hired, who will be stationed “on and around” transit. Crime has always been a problem on transit, and this plan seeks to fight that. There are also plans for campaigns against bad transit habits, like eating, drinking, and littering on vehicles.

The plan will see more police hired, who will be stationed “on and around” transit. Crime has always been a problem on transit, and this plan seeks to fight that. There are also plans for campaigns against bad transit habits, like eating, drinking, and littering on vehicles.

Adding more staff is always a risky endeavor, and police are expensive public employees who add to both current salary and future pension costs. Officials should carefully watch crime statistics to see if these new measures make a real difference to the transit system itself.

Private sector involvement includes private car-share and bus accommodation.

The plan includes a note that MTA has issued a request for proposals from companies to provide car-sharing services at MTA rail stations. This is a welcome involvement of private companies that seek to provide extra mobility options at public locations where they typically would not have access. The final form has yet to coalesce, but the plan gets points for seeking to accommodate private partners in public infrastructure.

Fairly sound plan, but questions remain

Overall, as transit projects go, BaltimoreLink is a fairly sound plan. But questions remain. Most importantly, it’s entirely unclear where the $135 million to implement this plan is coming from. It was not appropriated by the legislature during the past year’s budget negotiation.

Neither MDOT nor MTA have responded to requests regarding what authority it has to spend this money. One hundred thirty-five million dollars is not a small amount of budget authority, and any plan should not have been implemented without a clear source of funds for expanded service.

Nick Zaiac is a policy analyst at the Maryland Public Policy Institute.

GPS is essential to attract new riders. The system lost me when GPS was shown to fail.

The best way to shorten total commute times is to minimize waits. You can’t minimize wait if you don’t know where your bus is.

Any bus system is inferior to any rail system. You can’t rationalize that demographic differences between DC, Portland and Baltimore justify the disparity in rail spending here in Mobtown. The transit war is a mere offshoot of the ongoing class war.

It appears that there will be a number of miles of routes added to the bus system and that the planned BaltimoreLink routes will require a larger additional buses if they are to run every 10 minutes.

I have studied the BaltimoreLink website (with great difficulty) to see the impact of this plan on several of the bus routes I use routinely–just trying to answer the question of what buses I would have to take and how often do they run at the times I normally use them. Most of the routes I use will be replaced by three lines, which will mean more transfers and, from my point of view, a significantly increased probability of lateness and increased waiting times (in all weather) for riders on at least these heavily used lines.

Will more buses be added to the system to cover the additional miles and frequencies? Will a sufficient number of additional drivers hired to ensure there are enough drivers to compensate for absenteeism? If not, the plan will fail. Suburbanites won’t use it due to unreliability–they need to get to their jobs on time. And urban users will face longer waits and more transfers. The MTA has not been able to provide enough buses and drivers to operate the current or past systems despite years (decades?) of trying. Why should riders expect that $135 million will make an expanded system work by 2017, however intelligent the plan?

I do not drive and either walk or use buses, light rail, or Metro for nearly all of my transportation. I wonder how many of the designers of this new system have any regular experience relying on transit in Baltimore. If MTA Bus Tracker is any guide, the MTA doesn’t even know where many of it’s buses are (how many years ago was that announced to go live?),

If the designers were familiar with actual bus riding in Baltimore, they would realize that their plan must include solutions to ensure an adequate number of working buses and number of actual drivers are on duty to implement the schedule. I don’t know enough to question the theory behind the plan, it might be a great solution. But it won’t work without buses and drivers and I haven’t seen any mention of them.

Fix something that is broken instead of building something completely new that will need fixing. It appears that in this rare instance the government is acting somewhat logically.

This plan is crap. It uses high pollution busing instead of greener mass transit. We need a real rail system serving all suburban sides of the city like DC’s. It also eliminates very useful bus routes like the 120 Express that commutes many business workers from southern Harford county/White Marsh/eastern Baltimore county directly to downtown, an area that badly needs metro or light rail access to downtown. Just look at all of the traffic jams flowing up and down 95 onto 395 if you don’t think people still work downtown. I know a lot of very angry bus commuters as a result of this stupid decision. Most of the new express routes seem pretty useless too.

Well, perhaps Baltimore should have been founded as a PLANNED city like DC.