By Roy T. Meyers

Professor of Political Science, UMBC

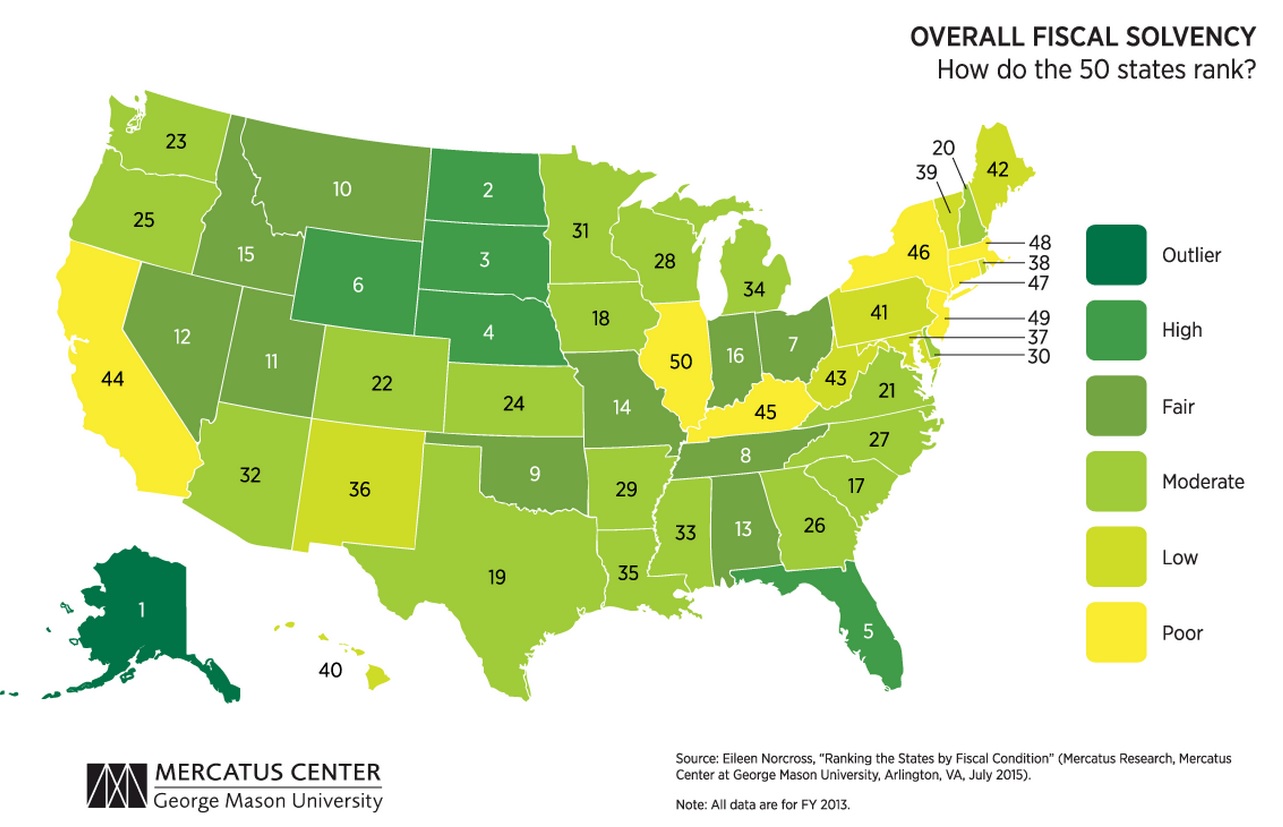

In a piece published last week by MarylandReporter.com, Randolph May of the Free State Foundation touted a recent Mercatus Center study that ranked Maryland only 37th best among the 50 states for its fiscal health.

This assessment is sure to be repeated in the coming year as politicians make budget decisions. So it’s important to understand whether this ranking makes sense, particularly when it is so low compared to the state’s AAA bond rating. Maryland is one of 10 states that now have that highest rating from all three major bond rating agencies.

The Mercatus study used accounting data from the states’ Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports (CAFRs) for fiscal year 2013, which are dated figures compared to projections for the current fiscal year, which is 2016.

Nevertheless, there are some good reasons to look at financial reports. They show much more comprehensive displays of state finances than does the typical focus in budgeting on the state’s general fund, which in Maryland is less than half the state’s spending. And the CAFRs use accrual accounting, which if done well can provide better though still imperfect measures of the states’ long-lived financial positions.

Grounds to question the rankings

However, while some of the Mercatus publication is informative, there are also good grounds for questioning the way that Mercatus used the CAFR data to construct its rankings.

Here’s one example. The report shows three ratio measures of cash solvency, or the ability to pay current bills on time: the cash, quick, and current ratios, the last of which is usually considered to be the most important.

On June 30, 2013, Maryland had a ratio of 2.10, which was below the mean (average) among the states of 3.37. Mercatus then converted the ratios of Maryland and the other 49 states into “z scores,” which are measures of how many standard deviations each state’s score falls above or below the mean. Maryland thus earns a “bad” score of -1.79.

But in fact, Maryland’s current ratio should earn a “good” score! A current ratio of 2.1 shows the state has twice as much in current assets as in current liabilities, which is easily more than enough liquidity (the rule of thumb minimum is a ratio of 1).

Why should Maryland keep more idle cash on hand, when those moneys could instead be used to pay for needed services or still be in the pockets of taxpayers?

Maryland efficiently managing its cash

My interpretation is that this current ratio may instead suggest the state makes accurate budget projections and efficiently manages its cash. That impression is certainly shared by the bond raters; if you look at their evaluations of Maryland’s debt, you won’t see any concerns about the state’s liquidity. And the Mercatus report implicitly acknowledges this: it states that “the z-score measures relative position in the ranking and does not translate into a direct measure of fiscal health.”

If that’s the case, why construct the ranking this way?

A problem with interpretation

A second problem is how the Mercatus ranking is being interpreted. Mr. May wrote “Maryland already suffers from a reputation as a state with excessively high taxes. So it will be important, going forward, to restrain the rapid growth experienced in the last many years in the level of expenditures.”

So let’s go to the Mercatus data to see what they actually show. The report uses three ratio measures of what it calls “service-level solvency”: taxes divided by state personal income (PI), revenues divided by PI, and expenditures divided by PI.

Note that these measures don’t compare the quantity or quality of services to measures of “need.” Instead, states earn higher rankings in the Mercatus approach by taxing and spending relatively little in relation to their income. With these low levels, states have more space to tax and spend more, if they choose to do so, and still remain financially solvent.

Here Maryland earns the 13th rank because its taxes, revenues, and expenditures are all comparatively low relative to its income. This is the opposite of the common perception that is parroted by Mr. May. Maryland’s “reputation as a state with excessively high taxes” happens to be false if the evaluation is based on a comparison to other states, which is what Mercatus does.

Rankings can oversimplify

It’s not news that political advocates use rankings to make their points, and there’s nothing wrong with that when the rankings are well constructed and understood. It’s also not unusual to hear criticism of rankings when they oversimplify reality.

Remember the claim based on the Education Week rankings that Maryland for years running had the best school system in the country? Conservatives said that this ranking system was flawed, in part because it counted how much was spent on education, when it is results that truly matter. They should give the Mercatus ranking system a similar level of scrutiny.

Even the best ranking systems can only do so much. Regarding education, there’s no question that Maryland has many great schools and teachers, which is the result of major investments and a lot of hard work. But there is always room for improvement, and some schools need a great deal.

The same could be said for MD’s finances–it has a AAA bond rating, and it does many things well, but the state also has important financial challenges. For example, its defined benefit pension system still needs additional reforms to build on the savings enacted in recent years. It would be better to focus on those opportunities for improvement than to twist the interpretation of a fiscal health ranking that itself is imperfect.

Professor Roy Meyers can be reached at meyers@umbc.edu.

Recent Comments