Over the years he has founded a number of startup technology companies, including several in the biomedical field. His name is on a number of patents and more recently one company he co-founded rolled out one of the first ever super-resolution microscopes for advanced technology.

His biggest challenge these days, however, is helping the state of Maryland become a leader in the burgeoning field of quantum computing.

In January, Gov. Wes Moore unveiled a plan to make Maryland the “quantum capital of the world,” earmarking $27.5 million in the 2026 state budget specifically for quantum technology investments and to support academic, technical and workforce development in the industry.

As director of the Quantum Technology Center, based at the University of Maryland, Walsworth is charged with building an ecosystem of startup companies and research labs that can share knowledge and collaborate across disciplines to quicken development of quantum products.

“There’s many elements to,” turning Maryland into the quantum capital, Walsworth said. “But one key element is taking the University of Maryland, which is already strong in quantum, and making it even stronger through things like building more laboratory space, hiring more faculty who will be experts in various aspects of quantum.”

For him personally, “it’s a chance to lead something and lead something intentional, to really craft it the way I want to do it, to help the technology translate and educate people in this interface discipline,” Walsworth said.

Recruited from Harvard

Walsworth was recruited to head the Quantum Technology Center in 2019. Prior to relocating to Maryland, Walsworth was a researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“Harvard’s wonderful, great students and faculty and all that,” but the opportunity to build something in his vision, he said, was an opportunity he couldn’t refuse.

Whether Maryland can achieve Moore’s goal is unclear. While Maryland companies have been working in the quantum space for over a decade, several have relocated to other technology-focused cities, including Boston.

Kelly Schulz, chief executive of the Maryland Tech Council, believes that Maryland’s financial commitment could change that and make Moore’s aspirations realistic.

“It’s going to show to other investors and other people that are interested in the sector, that Maryland is a place that wants to invest in growth in its tech industries,” Schulz said.

Quantum computers use the power of quantum physics to quickly solve problems and perform tasks faster than a conventional computer. Generally speaking, the speed at which a computer operates depends on how fast it can read 1’s and 0’s, known as binary code. And while modern computers read these commands with lightning speed, quantum computers operate exponentially faster by reading binary digits that are both a 1 and a 0.

As an example, Google unveiled a quantum computer in 2019 that could determine in 200 seconds whether a string of numbers was truly random or if there was a pattern involved.

Google claimed that a supercomputer without quantum capabilities would need thousands of years to perform the same calculations. In December, Google announced the development of a quantum computing chip that has been touted as a major advancement.

Unstable computers

The problem, however, is that quantum computers aren’t yet commercially viable. Quantum computers are sensitive and make errors, which degrades the quality of some computations. They also cannot maintain a quantum state for very long. Because a quantum state is inherently unstable, even the best quantum computers can only operate for short bursts of time. That means the quantum computer age is still years away.

But as Walsworth points out, quantum technology is not limited to quantum computers.

He believes quantum technology can be applied to a wide variety of uses and help develop new products in everything from mining to biotechnology. He has said in the past that work in the center’s labs will be used to “undertake key research to enable translation into technologies for real-world sensing, networking, and computing applications.”

The advancement of quantum technology is also of geopolitical importance.

The military, for example, wants to use quantum to create a device that can decrypt any encrypted file. The United States wants to achieve this goal ahead of foreign adversaries.

To that end, the Quantum Technology Center is working closely with the U.S. Army Research Lab, located in Adelphi, and the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science, also based at the University of Maryland, to research both quantum methods of encryption and developing quantum-resistant encryption.

Throughout his career, Walsworth has focused primarily on near-vacancy diamonds (or NVs for short) and their applications in technology.

He is one of the founders of Quantum Catalyzer LLC, a company that conducts quantum research for the government and the private sector and also operates as a for-profit business accelerator, which helps other quantum-related businesses get started.

Walsworth also has a hand in some of the companies that Quantum Catalyzer sponsors.

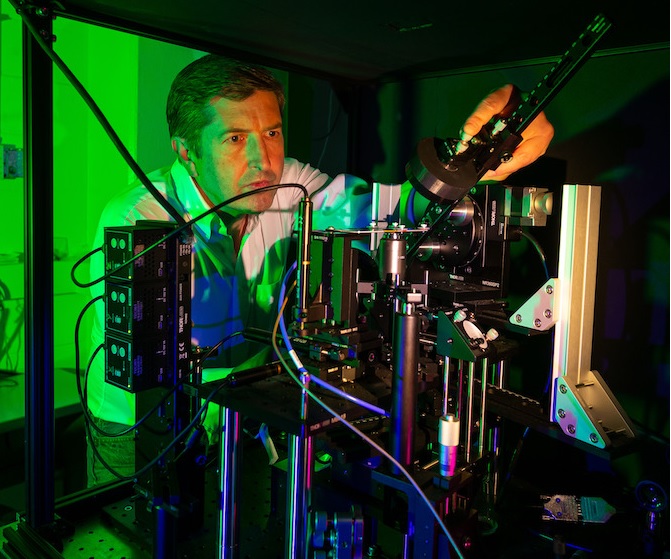

One such company is EuQlid, an early-stage startup company that builds diamond-based magnetic field sensors and the company responsible for the microscope spun out just last year.

This is no ordinary microscope: it allows the user to see immaterial things such as magnetic waves, allowing researchers to make observations with their eyes rather than with specialized equipment. EuQlid, based in College Park, was co-founded by Walsworth, along with EuQlid Chief Executive Sanjive Agarwala, Chief Technology Officer David Glenn and Quantum Catalyzer Chief Technology Officer Connor Hart.

Meanwhile, at the Quantum Technology Center, about a dozen people, many of whom Walsworth brought with him from Harvard, work to develop quantum solutions to scientific problems.

For example, UMD quantum technology professor John Blanchard is working with graduate students to build a machine that uses quantum technology to cool hydrogen atoms, allowing chemists to initiate reactions with the element much faster.

Maryland companies

There are also several companies in Maryland seeking to turn this technological frontier into marketable products.

Quantum Xchange in Bethesda, for example, helps companies enhance encryption and ensure that critical data remains secure.

“These things like 20, 30 years ago, were just sort of academic papers,” Walsworth said. “They were just people like proposing, maybe one day we could do this. But in the last decade or two, technology has progressed to the point that these things are actually happening in labs. And it’s the point that it starts to make sense to kind of take them out of the lab into the real world.”

The largest quantum technology company in Maryland is IonQ Inc., headquartered in College Park and started by two former University of Maryland professors with the goal of creating quantum computers for commercial use.

The company is closely watched on Wall Street, mainly because it’s one of the few public companies that solely focuses on quantum. Last week, IonQ stock surged nearly 40% after CEO Niccolo de Masi said he was highly optimistic about the company’s growth prospects.

“IonQ is one of the companies that they are talking about worldwide,” Schulz said.

But Maryland isn’t the only state hoping to get an edge in the quantum race.

Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker has made a number of announcements in the past year promoting investments in quantum-related projects, including the creation of the Quantum and Microelectronics Park in Chicago.

Massachusetts is also a destination for the world’s top quantum technology experts, including at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Quantum Engineering.

International Business Machines Corp. has been expanding the IBM Quantum Data Center in Poughkeepsie, New York.

And, of course, Google is working on quantum in Santa Barbara, California.

Nevertheless, Walsworth believes that Moore’s dream of Maryland quantum dominance is feasible. “There are only a handful of leading places in the world,” Walsworth said. “But Maryland is already one of those places.”

Recent Comments