The Columbia Flier newspaper, once essential reading in the early decades of the planned community in Howard County, will no longer be published, the Baltimore Sun Media Group announced Thursday.

The final edition of the newspaper is being delivered free to homes in Columbia Thursday, as it has been for the past 54 years.

The weekly paper once ran more than 100 pages a week in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, but in recent years, it has been a ghost of its former self. Its final edition is a mere 24 pages with only eight of those pages locally produced reporting.

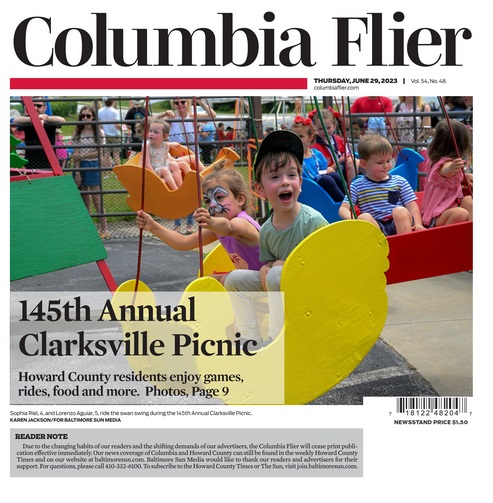

The closing was announced with a small box on the front page:

“Reader note: Due to the changing habits of our readers and the shifting demands of our advertisers, the Columbia Flier will cease print publication effective immediately. Our news coverage of Columbia and Howard County can still be found in the weekly Howard County Times and on our website at baltimoresun.com. Baltimore Sun Media would like to thank our readers and advertisers for their support.”

The history of the Flier and its importance to Columbia in the last century occupies six pages of my 2017 book “Columbia at 50: A Memoir of a City.” You can still read the chapter on the “Media in the New Town” online (and in fact all 12 chapters of the book) at MarylandReporter.com.

Rather than rehash it, here is what I wrote then (one of the few pieces of writing in which I still own the copyright.)

“Two years after Columbia Life folded and two non-journalism jobs later, a position finally opened at the Columbia Flier, where I had done some freelance writing. I had already helped the Flier move from its small flexi size into the tabloid it became in 1974, growing to 64 pages. After I became associate editor in 1975, I covered education, business and politics. In 1976, I wrote the cover story for its first 100-page issue, a piece titled “Banned Books” on efforts to ban some books from school libraries.

We now know that we were all working in the heyday of the newspaper industry — not just in Columbia or Maryland, but in the United States. Advertising revenues were bulging, profits were ballooning, staffing soared at every publication.

Love or hate it, but read it

There were people who loved the Flier; there were people who hated the Flier, particularly the liberal bent of its publisher Zeke Orlinsky and his weekly “Publisher’s Note.” But love it or hate it, people read it. At one point, a survey found that 92% of Columbians read the paper that landed free every Thursday on their doorsteps and driveways.

This was not your traditional newspaper produced by traditional newspaper people. Its models were magazines and the alternative city papers that grew out of the ’60s counterculture. Its editors didn’t just read The Washington Post and The New York Times, but The New Yorker and The Village Voice. It was in sharp contrast to its stodgy competitors, like the Sun.

The Flier’s sketchy origins in 1969 certainly gave no hint of the powerhouse it would become.

“I got pissed at something in the Howard County Times,” recalled Orlinsky in a recent interview from his home in Westport, Conn. “I didn’t have a vision.”

The first issue of the Flier was indeed a flyer — eight pages of legal paper folded with a Merriweather Post Pavilion ad on the front, ads for cars and tires, and a calendar of events. This first issue on Columbia’s June birthday in 1969 was reprinted several times over the years as a reminder of how far the newspaper had come.

When Jean Moon joined the fledgling operation as a writer two years later, free circulation had grown to 9,000, and there was real news in the Flier, but they were still cutting and pasting the typewritten copy on a dining room table.

At the time, Orlinsky wrote: “To reflect the growth of a new city like Columbia is to meet new challenges. It calls on a publisher to throw away the old and tired concept of journalism. Journalism is more than just information and news. Journalism should excite and guide a community.”

That statement was still being pointed to 20 years later in a history of the paper given to new staff members of a much larger enterprise.

Moon, who had come to Columbia with her husband Bob for his job as an architect at the Rouse Co., was totally on board with the concept of community journalism — “that we weren’t dailies” and the mission was to “play a role in the community,” she recalled recently.

The Columbia Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway has sat vacant for 12 years and may be town down. Photo by Len Lazarick.

By 1973, Moon was editor and general manager, she had hired [Tom} Graham,{who died in 2022] and the staff had grown several times. By the time I joined the staff on July 31, 1975, it was operating out of a building on Route 108. It moved again to Wilde Lake Village Center, and in spring of 1978, we moved into the Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway, an unusual building designed by Bob Moon, standing out amid the town’s bland architecture, with its white metal sides and sloping fronts of glass.

There were no crusty old editors looking over our shoulders, telling us “we don’t do that here.” Jean and Zeke — and we often talked about them that way in this family-like operation — were still in their 30s; Tom and I were in our 20s, and the staff was of similar age. While Tom and I did take photos, we eventually brought on a staff of talented photographers who made that a hallmark of the paper in future years.

The Flier was more than just a writers’ paper. What’s striking going through boxes of old clips I dragged out for this series was how closely we covered this new community — the opening of restaurants, the closing of stores, the community dustups, the arguments over tot lots and door colors, the nitty-gritty of everyday life. While there were wonderful photo spreads and long features, there was also column after column of “notices” about routine events and meetings.

Because of Jean Moon’s proclivities, there was massive coverage of the performing arts, not just in Columbia (Merriweather Post Pavilion was going strong as a venue for big acts), but in Washington and Baltimore too.

There was local sports galore including the long-time weekly column by Stan Ber called “Bits and Pieces,” a column that predated my arrival and survived long after I left 21 years later. Stan, like many of the other writers, was community bred. His day job was at the National Security Agency where he did what can never be disclosed and where they answered the phones cryptically with the last four digits of the extension you called.

Most of us lived in Columbia. We were part of the community, and the community was part of the paper. Page three had the signed “Publisher’s Note” — none of this unsigned editorial page stuff of the old school — and then there were the letters, so many letters from Columbians, often complaining about Zeke’s emotional diatribes or other coverage that pushed the envelope, like the time we put the full-page image of a mammogram on the cover to illustrate a story on breast cancer.

The Flier was the way the community talked to itself, understood itself, remembered itself.

The advertising flowed in — all the newspaper staples — cars, groceries, real estate, classifieds. “The smartest thing was not selling ads by the inch,” as dailies did, producing those odd-shaped page wells, Orlinsky said. The Flier sold eighth-, quarter- and half-pages that made design easier and more attractive.

More advertising meant more money, more pages, more stories to fill them, more staff to write and illustrate them, and more listings — and made it a more attractive target for acquisition.

The Sale of the Flier

The night of Nov. 7, 1978, a major gubernatorial election, I was covering the returns in the Kiwanis Hall in Ellicott City, and a reporter from the Howard County Times asked me my reaction to the sale of the Columbia Flier.

I was floored. Sale, what sale? Jean had tried to have me tracked down that night — this was decades before cell phones — so I would not learn of the deal from our local competitors who had gotten wind of it.

Who were these guys at Whitney Communications? Turns out these guys — and yes, they were all guys — were some of the classiest in the business. The chairman, Walter Thayer, had been the publisher of the vaunted New York Herald Tribune, and the president was John Prescott, former president of The Washington Post Co. Millionaire John Hay Whitney had founded the company.

It was one of the best things that ever happened to us. Jean and Zeke were left fully in charge. A year later we bought The Howard County Times and other papers in the chain. I got to spend full-time in Annapolis during the 90-day sessions as political editor. When John Hay Whitney died in 1982, the partners created a working fellowship that sent Tom Graham and then me to Paris for a year at the International Herald Tribune, where Whitney had been the managing partner of a three-way ownership split with the Post and The New York Times.

We won award after award, both state and national, for writing in many categories, photography and design.

The Flier kept chugging along, and in 1988, our newspaper group, now called Patuxent Publishing, bought Times Publishing in Towson and its five newspapers, including the Towson Times and The Jeffersonian. I became managing editor of seven Baltimore County papers.

“We never recovered from that purchase,” said Jean Moon in a recent conversation. In hindsight, she said, “We overpaid for those newspapers” and struggled to make them generate enough return on that investment.

Management began making cuts in the 1990s as Maryland experienced a harsher recession than the rest of the country. In 1995, a Whitney Communications partner and Zeke told Jean Moon she needed to go, and in June 1997, six months after I left, Patuxent and the Flier were sold to the Baltimore Sun and its new owner, Times-Mirror.

“I really don’t think [the sale] will change anything” about the newspapers, Orlinsky told me for a story I wrote about the sale in The Business Monthly. “It’s not in their interest to screw it up.”

Orlinsky stayed on as a consultant for a year, having twice sold the same paper at a handsome profit. He was wrong about nothing changing.

Orlinsky says now [in 2016] he had seen some of the handwriting on the wall a few years before as the Internet began to spread. “I didn’t understand it” but “I knew that it was only a period of time [before] newspapers would lose those categories” of classifieds — employment ads, real estate and cars.

What began as small dips in revenue in the 1990s became a steady downhill slide and then, in 2008, as the Great Recession hit, newspaper revenues fell off the cliff. As advertising evaporated, pages and coverage were cut, as were the reporters and editors who produced them.

Along the way, Times-Mirror sold the Sun and the local papers to the Tribune Co., which went private and then bankrupt for years, and now has the god-awful name of tronc. Over the years it has decimated staff and closed offices, including the Flier building on Little Patuxent Parkway in 2011.

The Flier is now run by editors in the Sun’s downtown Baltimore building. What were once several independent news operations in the city and the five counties that surround it are now under one owner, the Baltimore Sun Media Group, with copy shared among all. In the Flier you can read articles you may have already read in the Sun, or the other way around.” [Copyright 2017 Len Lazarick]

It’s only gotten worse

I wrote that in 2016. It first ran in what still is the only locally owned newspaper, The Business Monthly, serving Howard and Anne Arundel counties.

Since then, the situation has only gotten worse. In 2021, Tribune Publishing, which has reverted to its old name, was purchased by Alden Global Capital, a hedge fund known for dismantling its media holdings and selling off its assets, as it has done in Baltimore. The former Sun building in what was then called Port Covington is soon to be demolished as part of the Baltimore Peninsula development.

The Sun itself is printed in Wilmington, Delaware, having sold its printing presses.

Sorry to hear this news, the times are constantly developing and progressing, in the process there will always be new things to replace traditional ones.