Tragedy is a term loosely used for anything awful that happens to people who don’t deserve it. But in the original sense of ancient Greek dramas, tragedy is the fall of a high-born, privileged, and powerful man whose own character flaws bring him to ruin.

Aided by his privilege, connections, and status as a war hero, he eventually was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, the U.S. House, and finally, the U.S. Senate, where he was an ally of Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Along the way, he becomes dangerously addicted to alcohol, which had plagued his own father and other family members.

Aided by his privilege, connections, and status as a war hero, he eventually was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, the U.S. House, and finally, the U.S. Senate, where he was an ally of Presidents John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Along the way, he becomes dangerously addicted to alcohol, which had plagued his own father and other family members.

Once seen as destined for great things, he winds up a drunk who makes unpopular political choices for the 1960s as a staunch supporter of civil rights legislation and the Vietnam war. Booze-filled bad personal choices in marriage and staffing eventually lead him to lose his reelection, his family, and a six-year battle to defeat federal charges of bribery.

This is the tragedy of Daniel Baugh Brewster detailed with great skill, empathy, and meticulous research by veteran journalist and author John Frece in his new book ominously titled: “Self-Destruction: The rise, fall, and redemption of U.S. Senator Daniel B. Brewster.”

Connections

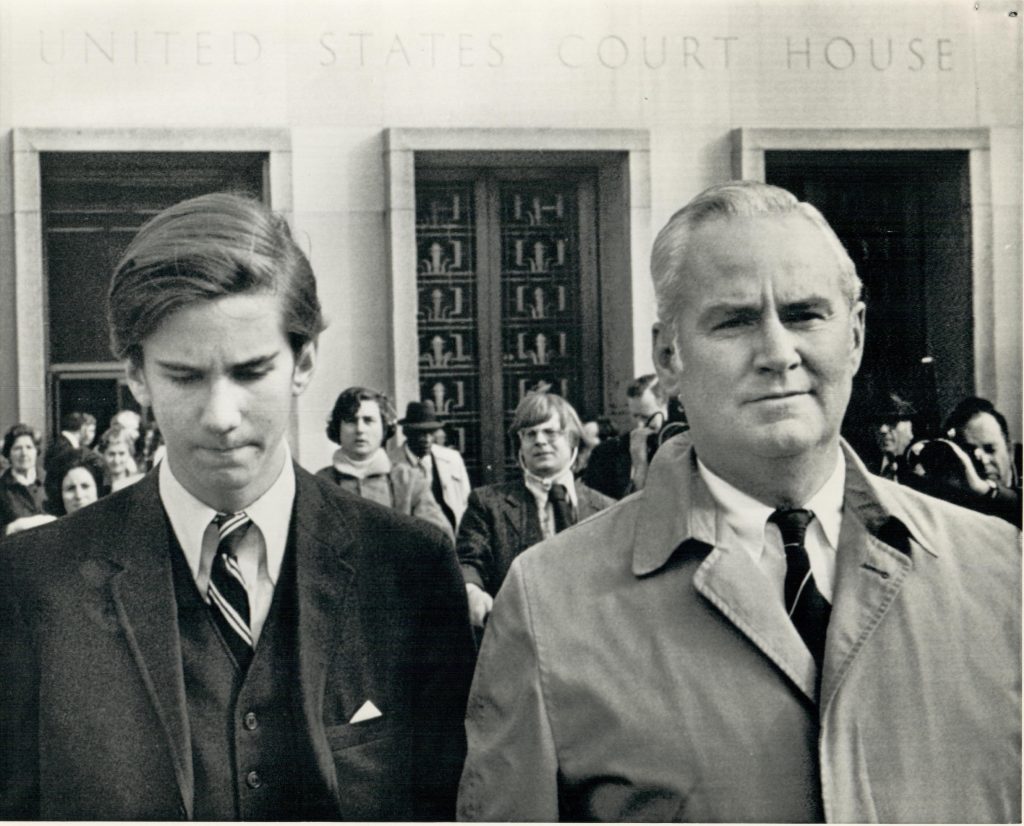

Former Sen. Danny Brewster, right, and his son Gerry leave a federal courthouse in Washington on Nov. 17, 1972.

I only met and interviewed Brewster once but have strong personal connections to many of the people and events in his life. As managing editor of the eight Patuxent Publishing newspapers in Baltimore County, I had come to know the Green Spring Valley and the wonderful steeplechase races over the plush farmlands there. These are great athletic and social occasions for the old money like the Brewsters that raised the thoroughbreds they raced to jump fences and chase hounds.

Our papers covered son Gerry who served as a delegate and ran unsuccessfully for Congress. The book reveals Gerry worshipped his father but was angry and resentful about his absence from the home and the lives of his sons.

Through my decades covering Maryland politics, I knew not only Frece, but several of Danny Brewster’s close friends, such as Gov. Harry Hughes and Republican Sen. Mac Mathias, who despite his friendship defeated him for re-election. I also knew the sources deeply quoted in this book, people like Rep. Steny Hoyer and Blaine Taylor, my argumentative late friend, military historian, and perennial candidate for Congress in both parties.

The helmet was worn by Marine Lt. Daniel Brewster on Okinawa on April 2, 1945. The Japanese sniper’s bullet made the small hole on the upper left of the helmet and exited through the larger hole in the center. An inch lower and it would likely have killed Brewster. Brewster Family photo

Most importantly, I had studied the brief but pivotal event in his life, as it was for my Army private father: the battle for Okinawa in 1945. I interviewed Danny Brewster on his farm as I was preparing to go with my father to Okinawa in 1995 for the 50th anniversary of the battle. There we dedicated memorial tablets for over 240,000 dead Americans, Japanese troops, and civilians, a third of the island’s population. In Brewster’s office there, I got to see his helmet with the holes the sniper’s bullet made — a slight shift, and the Japanese sniper could have killed Brewster in the ambush on the second day of the battle.

Forgotten battle

Readers could be forgiven for not knowing much about Okinawa, other than it hosts the U.S. military bases closest to Taiwan and China. Because the battle was so devastating, the tale has none of the charm of the Normandy countryside and its quaint villages and ancient churches.

“The fight for Okinawa would grind on for nearly three bloody, muddy, miserable months,” Frece writes. “It would become the biggest, most savage, and – as it turned out—final major battle of World War II. It was a kill-or-be-killed struggle. Neither side took prisoners,”

“The battle involved more troops, more ships, and more supplies than the Allied landing on the beaches of Normandy one year before.”

“Kill or be killed,” was the phrase veterans of the battle would use 50 years later.

There are no movies glorifying this invasion. Most recently, Hacksaw Ridge, the tale of a conscious objector who serves as a brave army medic, provides a glimpse of the fighting that lead to 100% casualty rates (dead and wounded) for the four Army and three Marine divisions in the island battle.

My father earned two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star for valor; Brewster was wounded seven times and earned the same medal. Both were patched up and sent back into the fight. The battle also produced more incidents of “combat fatigue” – 26,000 of what we now call post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD) — than any fighting in the war. For both sides, the enemy was close, lethal, and mind-blowing.

Alcohol

This set the context for the rest of Brewster’s life. Frece counts it as one of the causes of his alcoholism, but it was a disease that ran in Brewster’s family. Danny’s father of the same name, a decorated veteran of World War I, died from drinking at 36. As alcoholics point out, there are endless reasons to drink.

Returning home as a war hero, Brewster settled back into the privileged life of the horse country, earned a law degree, joined a politically connected Towson law firm, and was elected to the House of Delegates in 1950, then to Congress, and finally to the U.S. Senate. He was “the golden boy” of Maryland politics.

As Frece sums up very early in the book: “Brewster’s story is one of wealth and opportunity, of personal courage and political stardom. But it is also the saga of a tragic fall and political humiliation, and of a self-inflicted political incapacitation that nearly proved fatal. The tale reveals the lifelong effects of trauma experienced by many World War II veterans …yet is also the story of recovery, of new beginnings, of personal resurrection.”

Biographies and memoirs put a human face on history. Frece’s bio puts Danny’s life in the middle of Maryland’s political history from 1940 through 1970. While Maryland’s population grew rapidly during the war from manufacturing, and the suburbs after, it was still a marginally Southern state. Racism wasn’t just systemic, it was the system in schools, work, and housing, as Brewster found out to his political peril.

Brewster was a strong supporter of President Johnson and his push for civil rights despite his longstanding opposition to those rights as a senator from Texas. Johnson asked Brewster to run in Maryland as his surrogate for president in 1964, a request.

“I simply could not refuse,” the senator said. On the ballot, Brewster faced Alabama Gov. George Wallace, the arch-segregationist who assembled a coalition of angry and disaffected white voters.

To Brewster’s shock and dismay, Maryland Democrats gave Wallace 44% of the vote. For someone of Brewster’s stature, “even in victory, it felt to many like a defeat,”, especially to the senator, Frece writes. It caused Brewster to lose self-confidence and maybe triggered an increase in drinking. He was booed, cursed, spat on, and got a flood of nasty mail and phone calls He was called a traitor to his race.

“I totally misunderstood the depth of racial hatred and bigotry in the state,” Brewster told The Baltimore Sun in a 1980 interview. “I was amazed, staggered, disheartened, and bitterly disappointed, and I seriously considered dropping out of politics.”

In 1966, Brewster and Sen. Joe Tydings split from the Democratic establishment they were part of to back Rep. Carlton Sickles for governor. The split led to primary plurality for George Mahoney, whose slogan, “Your home is your castle” was an implicit endorsement of the segregated neighborhoods at the time. Liberal Democratic voters then voted for Republican Baltimore County Executive Spiro Agnew, who eventually became vice president to President Richard Nixon. (He was later forced to resign after continuing to take bribes from his Baltimore County days.)

Worst mistake

Brewster’s loyalty to LBJ and his own service in the Marine Corps, where he had become a colonel in the reserves, were the source of what he later called “The worst mistake in my whole political career – supporting the war policy in Vietnam.” Frece says Brewster was Johnson’s “go-to man in the Senate on Vietnam.”

As the war dragged on and tens of thousands more draftees were sent to Vietnam and some came back in body bags, Maryland and the country become bitterly divided. Tens of thousands marched in the streets to oppose the war. At the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago, Brewster gave a routine speech thanking Mayor Richard Daley for hosting the convention. Outside the hall, the city’s cops were beating up anti-war protesters with batons. TV viewers saw both events. “It was an unmitigated disaster,” Brewster later said.

And along with the downward trajectory of his political fortunes, there was the downward spiral of his drinking. Frece sees politics as encouraging drinking but others might see alcoholism as the cause of his other problems. He suddenly divorced his well-liked first wife Carol, Gerry’s mother, who often filled in for him on the campaign trail to marry the first love of his life, horse breeder Anne Bullitt. Brewster was her fourth husband.

Prosecution and aftermath

His heavy drinking and inattention to Senate duties certainly contributed to his federal indictment for bribery – largely engineered by his chief of staff Jack Sullivan. Sullivan was not only the questionable chief witness for the federal prosecution led by U.S. Attorney Steve Sachs, later Maryland’s two-term attorney general; Sullivan had also engineered the deal.

The prosecution and appeals all the way to the Supreme Court dragged on for six years. Brewster was found not guilty of taking a bribe, contrary to what would later be reported. But to end the saga, he did reluctantly plead “no contest” to the lesser and rather curious misdemeanor of “accepting an illegal gratuity without corrupt intent,” even as his drinking went on and off.

People who know Brewster well – friends, family, staff – never believed he did anything crooked or criminal. He eventually sobered up, joined A.A., married a third wife who he met in therapy, had three more children to whom for once he paid attention, got back a horse farm and back into racing. He was appointed to numerous commissions and civic endeavors.

Despite his problems, he never lost the affection and respect of his staff. That included one young Baltimore woman who served as his receptionist in his early days in the Senate named Nancy D’Allesandro, daughter of a mayor and congressman. After marrying and moving to California, decades later she became the first woman speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

At the close of her foreword to Frece’s book, Nancy Pelosi says: “In the end, Danny led a life of meaning, purpose, and service. He was a good man who loved his family. As his good friend, I am grateful that his story will finally, fully be told.”

RELATED STORIES

Okinawa: 75th Anniversary of the Last Great Battle of the Pacific War

The article below includes a 1995 interview with Danny Brewster.

Great background article, thank you

Thanks for an informative look back in time, especially the personal insights and the background on Okinawa.