By Phil Caroom

The COVID-pandemic has exposed major systemic problems in Maryland’s prisons that have been ignored for years.

Let’s compare the population and COVID impacts on two populations:

| Area | Population | COVID cases | Percent |

| Central Annapolis (21401) | 36,012 | 2503 | 6.9% |

| Maryland Prisons | 18,400 | 3842 | 20.8% |

With a population half of Central Annapolis, the prison infection rate is roughly three times that of the state’s capitol. And these statistics exclude the huge impact on prison staff who also have become infected.

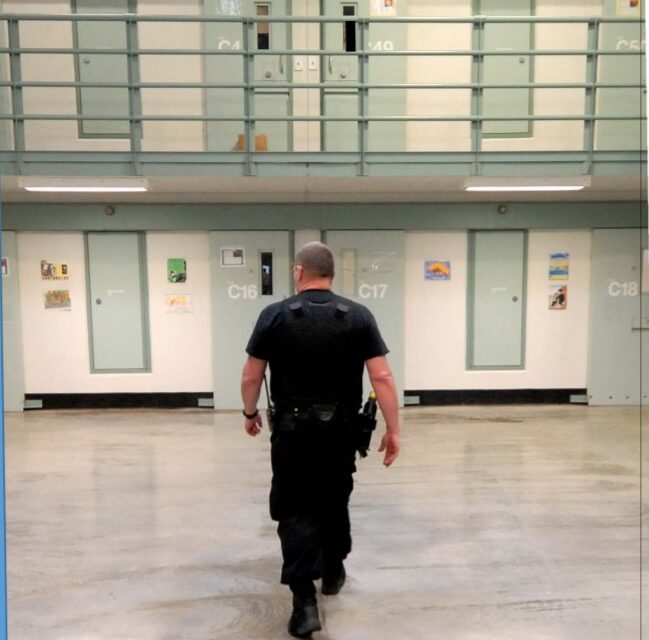

Why? Prisons, of course, are “congregate living” facilities – people are housed close together. The faculty at the Johns Hopkins medical and public health schools recommended early in the pandemic for the state to release nonviolent and vulnerable elderly, so that the remaining prisoners could have “social distancing.” But the state has failed to do so except for a small percentage.

Moreover, according to prisoners’ reports, correctional officers in many prisons have refused to wear face masks. Many prisoners reported being given one disposable facemask to use for months and insufficient soap for personal hygiene. Prisoners with COVID symptoms often are not actually tested but are returned to the general population.

The prison administrators deny these reports and, instead, give glowing accounts of efforts to protect prisoners’ health. But conflicting statements from correctional officers’ unions, news accounts and the infection rates give credibility to the accuracy of prisoners’ reports.

The COVID health crisis demonstrates the proverbial “tip-of-the-iceberg”, and this is only one of many problems camouflaged by well-intentioned denials from the state officials.

Other problems in Maryland prisons

Here are some other examples of problems all too well-known by prisoners, their families, correctional officers and volunteers:

Smuggling of illegal drugs: The state, often, cracks down on prisoners’ family members accusing them of smuggling illegal drugs into the prisons. Occasionally, that may happen. But, much more often, the source of illegal drugs is found to be corrupt correctional officers and staff. In the last five years alone, 125 people have been indicted for drug smuggling through three Maryland prisons – in each case with correctional officers as ringleaders. See this Washington Post article.

Smuggling of other contraband and illicit sexual activity: The most recent crackdown by federal prosecutors also involved correctional officers bringing cellphones, pornography and other contraband, as well as engaging in sex with prisoners. The operation was discovered as the result of a tip from a prisoner. See “Maryland prison smuggling ring,” April 19, 2019- Baltimore Sun.

Solitary confinement, officially known as “restrictive housing,” is overused in Maryland prisons at roughly twice the U.S. average. Correctional officers offer reasons for each use that prisoners often dispute. While “inmate grievances” can be filed, the process is so procedurally fraught and time-consuming that they are never resolved. See “Grievance System Broken” in the Baltimore Sun.

Violent gangs: Prison officials generally complain about multiple violent gangs that have spread through Maryland prisons. See, e.g., “Maryland Prison Gangs: Who Are They?” Delmarva Daily Times, 1/2/19. However, state prison administrators have not succeeded in changing the culture among imprisoned Marylanders to offer a real and positive alternative.

Just as 2020 events have led to reassessment of U.S. police powers and oversight, our COVID-interruption of business-as-usual in Maryland prisons should open our eyes to better options there.

Maryland Alliance for Justice Reform (www.ma4jr.org) and other advocates are asking the Maryland General Assembly to try evidence-based remedies to change our state prisons’ culture from one focused primarily on punishment and concealed operations to one that prioritizes rehabilitation and transparent operations.

Here are four bills that could begin the sea-change needed behind the walls where systemic racism has disproportionately impacted Maryland’s African-American population:

Four bills to change the system

- The Correctional Ombudsman bill, HB1188, would offer independent oversight, public reports, and rapid mediated solutions as done in other states.

- The Maryland Model Prisons Study Workgroup, HB698, would follow other states’ example, creating character-building academies for young offenders within the prisons, eliminating violence.

- Credits for education, HB89, would offer inmates incentives to boost their participation in earning degrees and marketable vocational certificates, proven to reduce recidivism.

- The Stepdown Program, HB131, calls for reduced solitary confinement and increased reentry resources for inmates before their release.

Recent Comments