By Jeremy Cox

Bay Journal

A national wildlife refuge that attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year to the Chesapeake Bay may be forced to close to the public soon.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering shuttering the Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge because it lacks the funding to hire a new refuge manager, said Marcia Pradines, project leader at the Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex, a branch of the service that oversees the Chesapeake region’s national refuges.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering shuttering the Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge because it lacks the funding to hire a new refuge manager, said Marcia Pradines, project leader at the Chesapeake Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex, a branch of the service that oversees the Chesapeake region’s national refuges.

“If the position isn’t filled, that’s a possibility,” Pradines said, “It’s not something we want to happen. In the end, it’s a budget reality.”

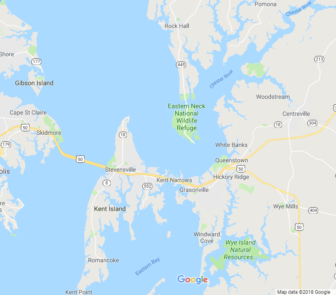

The refuge consists of a 2,200-acre island lying on Maryland’s Eastern Shore where the Chester River meets the Chesapeake. About 70,000 people visit each year to catch glimpses of tundra swans and more than 200 other bird species, hunt deer and turkeys, and hike among the island’s pine trees and saltwater marsh, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service

“People just like to drive down there sometimes,” said Melissa Baile, president of the Friends of Eastern Neck, a support group for the refuge. “You just feel the peacefulness. It’s just easy to get away when you go down there.”

Manager position empty

The manager position has been empty since last September, when Cindy Beemiller left for a refuge on Long Island. The financially strapped Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t have the funding to fill the position, Pradines said. Beemiller was one of two paid employees assigned to the property; the other, a maintenance worker, is all that remains.

If Congress doesn’t appropriate significantly more money for the refuge system for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1, Eastern Neck may have to close to the public, she said, adding that it’s unclear when agency management would make that call.

The extent of the shutdown would depend on funding availability, Pradines said. The Kent County road that traverses the island would remain open to Bogles Wharf, home to a county-maintained boat ramp and small pier. But the access gate across the road leading into the refuge would be closed, barring access to the visitor center as well as the five walking trails and two boardwalks.

It’s possible that trail maintenance and other activities would cease, Pradines added.

As the agency ponders its next step, employees from the Marshlands complex’s headquarters in Dorchester County have been sharing the refuge’s administrative work — and the four-hour roundtrip drive that accompanies it.

Migrating birds at the Eastern Neck Wildlife Refuge. Bay Journal photo by Dave Harp

Volunteers step up

The all-volunteer Friends of Eastern Neck has stepped in to complete other chores. In addition to their longtime responsibility of managing the visitor center, members are helping to conduct special events and performing countless hours of repairs and upkeep across the island.

At times, the island is devoid of personnel support, save for a lone volunteer clerk manning the front desk, said Phil Cicconi, vice president of the Friends group. Although refuge staff installed a panic button, many of the older, female volunteers feel unsafe.

Shutting down the refuge, he said, would cause it to fall into disrepair and potentially attract relic-hunters who operate “like ninjas in the night.” The island is a cache of American Indian artifacts. Cicconi worries that thieves might strip anything of value from the visitor center building, a renovated 1930s-era hunting lodge.

Early English settlement

The island was one of the first English settlements in Maryland. In 1650, Maj. Joseph Wickes received a grant for 800 acres of land and constructed a mansion that has since disappeared. Eastern Neck became Kent County’s seat; Wickes, its chief justice.

The Friends group’s latest task, Baile said, is writing letters and emails to elected officials and Fish and Wildlife staff to keep their beloved refuge open. They have lined up a growing list of allies in the fight, including the Kent County Commissioners, Patuxent Bird Club and Friends of Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge.

The Friends group also has partnered with their counterparts at Blackwater to create a website to fan public support: friendsofblackwater.org/help-eastern-neck.html.

“We’ve done everything we think we can do,” she said.

But it may not be enough. Eastern Neck is the latest refuge in an expanding slate that has faced cutbacks and potential closure because of a lack of federal investment, said Desiree Sorenson-Groves, vice president of government affairs with the National Wildlife Refuge Association.

Sunset over the Bay from the Eastern Neck Wildlife Refuge. Bay Journal photo by Dave Harp

$100 million less for refuges

Accounting for inflation and fixed costs, the nation’s network of more than 560 refuges receives nearly $100 million less funding today than in 2010, according to the Cooperative Alliance for Refuge Enhancement, a coalition of wildlife, sporting and conservation groups. The funding crunch has led the Fish and Wildlife Service to leave 488 refuge jobs unfilled, a loss of one out of seven positions.

“It’s a nationwide system problem. What’s happening in Eastern Neck is happening all across the United States,” Sorenson-Groves said. “You can limp along for a few years, tightening your belt and no travel and, whenever somebody retires, you don’t fill the position. But at a point, you can’t do anymore.”

Across the country, many refuges over the past 15 years have been forced to shut down visitor centers or cut back on the number of days they’re open, she said. The popular J.N. Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge in Florida, for example, was forced to close its visitor center two days a week after it lost two park rangers to budget cuts.

In Rhode Island, the Sachuest Point National Wildlife Refuge visitor center was closed for three consecutive winters. Supporters raised money to install solar panels, cutting costs enough to allow it to open for the winter of 2008-2009.

The Trump administration requested $473 million in funding for the refuge system in fiscal 2019, a 2.7% decrease from current spending.

Congress must act

An Interior Department appropriations bill approved by the House along party lines in July sets aside nearly $489 million, a rise of less than 1%. That slight increase, if passed in the Senate, would have little effect on the refuge system’s staffing and maintenance woes, Sorenson-Groves said.

“You have to understand that you can berate the administration as much as you want, but ultimately it comes down to the legislative branch — Congress — to appropriate the money,” she said.

Eastern Neck’s supporters look to Rep. Andy Harris, the Maryland Republican who represents the Eastern Shore, as their best hope for action. He is a member of the powerful House Appropriations Committee and belongs to the controlling party.

But Harris said his hands are largely tied.

“The Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge is a valuable resource in Maryland’s first district,” he said in a statement. “While an amendment earmarking funding specifically for Eastern Neck would violate congressional rules, I am actively investigating this issue and exploring solutions that will allow the refuge to continue providing services to Marylanders.”

For her part, Baile said she hopes to find a sympathetic ear when the refuge system’s Northeast district head, Scott Kahan, visits Eastern Neck during his annual field trip toward the end of August.

“People love this refuge. We have good visitation. It services not only our local community but also people from all over the country,” Baile said. “You’re willing to close down a whole refuge over $25,000 or $30,000? It’s a question of him prioritizing other things over us.”

About Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge

- Established: 1962

- Where: An island at the mouth of the Chester River, 15 minutes south of Rock Hall on Eastern Neck Road.

- Size: 2,285 acres

- Activities: Hiking, birding, wildlife viewing, hunting deer and turkey, paddling, fishing, crabbing

- Notable wildlife: Tundra swans between November and March, bald eagles, Delmarva fox squirrels, Canada geese, diamondback terrapins, white-tailed deer, beavers. To view a list of recent bird sightings, visit ebird.org/places/usfws and search for Eastern Neck National Wildlife Refuge.

The U.S. Dept of Interior could, with the greatest of ease, pay for this field manager position by cutting one desk job in HQ. Andy Harris hopefully can bend the ears of the right Trump Administration official.

Maybe if the state didn’t waste so much money on illegal aliens it could afford to fully fund nature preserve issues. AND have a higher level of safety to boot. (See recent article in Bethesda Beat on Mont Co’s uptick in GANG VIOLENCE)