By Jeremy Cox

Bay Journal

Only on Smith Island would someone get choked up about a jetty, a constructed wall of stones that functions like a bulwark against waves and water currents.

Eddie Somers, a civic activist and native of the island in the middle of the Chesapeake Bay, delivered remarks at a recent press conference called by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to mark a milestone in the construction of two jetties off its western flank. He was close to finishing when he suddenly stopped, holding back tears – tears of joy.

“Those barrier islands were in danger of breaching in a couple places, and when that happens, you’re one hurricane away from losing your home,” he said when asked later about the moment. “So, for a lot of people, it’s emotional — not just me.”

On Smith Island, Maryland’s only inhabited island with no bridge connection to the mainland, residents prize self-reliance. But for more than two decades, Somers and his neighbors had been pushing for outside help to save their low-lying island properties from slipping away into the surrounding Bay.

Now, they’ve gotten it. Since 2015, federal, state and local sources have invested about $18.3 million in three separate projects on and around Smith Island, adding about two miles of reconstructed shoreline, several acres of newly planted salt marshes and hundreds of feet of jetties.

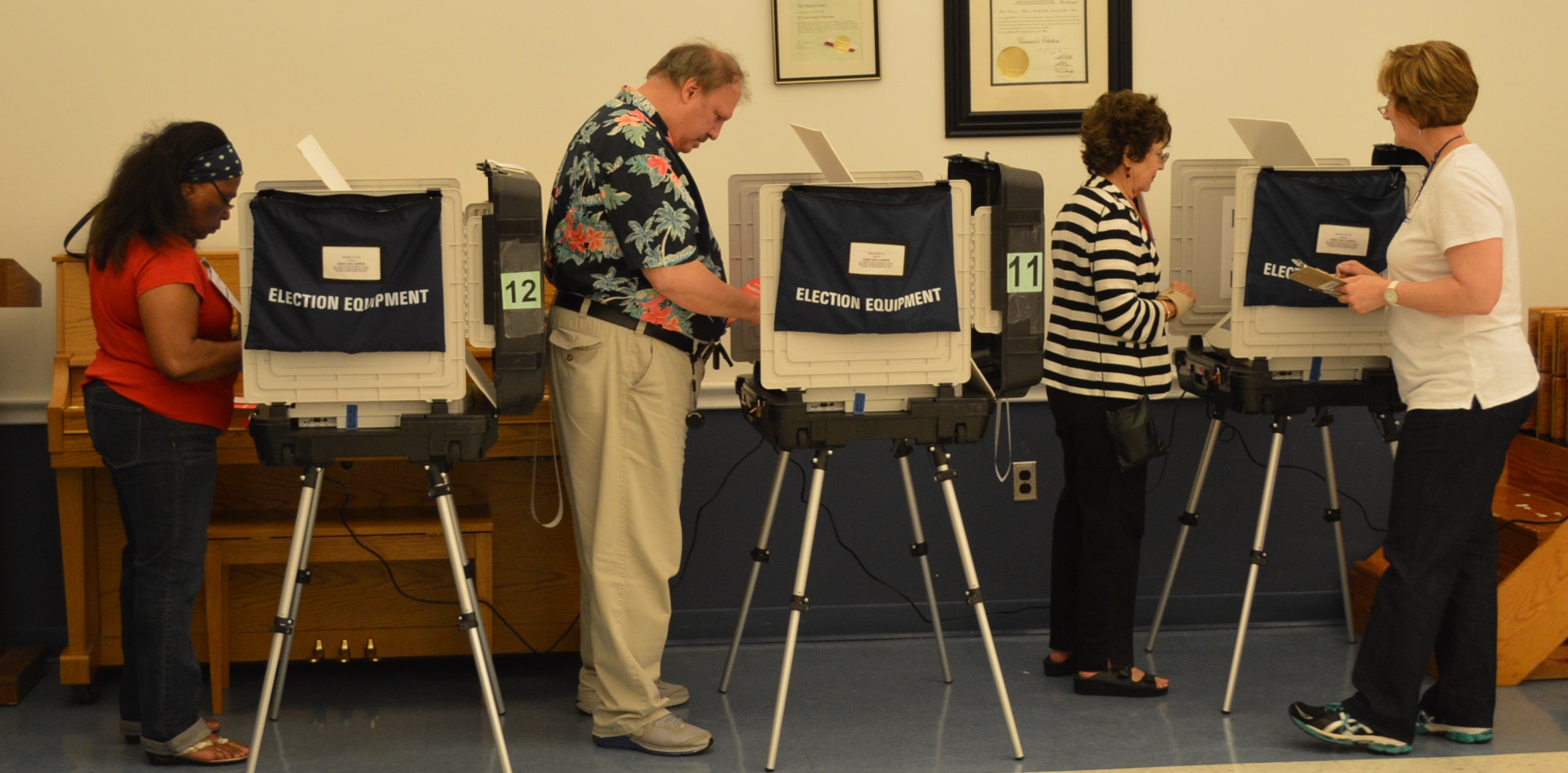

Two jetties extending out into the Chesapeake Bay were constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to protect a navigational channel near the Smith Island community of Rhodes Point. Bay Journal photo by Jeremy Cox

Buying time

That money may buy a lot of jetty stones and sprigs of cordgrass, but all it can really buy is time, according to climate researchers and Army Corps officials.

Smith Island is an archipelago, with a population spread across three small communities: Ewell, Rhodes Point and Tylerton.

Since 1850, erosion and rising sea levels have put about one-third of the islands underwater. By 2100, the Bay is expected to rise by at least 3 more feet – bad news for a land that’s mostly less than 3 feet above current sea level.

Clad in fatigues, Col. Ed Chamberlayne, head of the Army Corps’ Baltimore District office, boarded the Maryland Department of Natural Resources research boat, Kerhin, after the press conference to tour the new jetties with an entourage of state and local officials. He described the $6.9 million project, which also includes dredging a boat channel and using the fill to restore about 5 acres of nearby wetlands, as a temporary fix.

“How long this will last is an obvious question,” Chamberlayne said. “As far as what this does to Smith Island long-term, this is not a cure-all.”

Nor are any of the other projects. So, with each inch of sea level rise and dollar spent fighting it, an old question gains more urgency: To what lengths should society go to defend Smith Island and other places believed to be highly vulnerable to climate change?

How much should we spend?

Facing land losses of their own, coastal communities in Alaska and Louisiana are getting ready to relocate to new homes farther inland.

A similar debate hit Tangier Island, about 10 miles south of Smith Island in Virginia waters, after a 2015 Army Corps study declared that its residents may be among the first “climate refugees” in the continental United States. In the wake of a CNN report about the shrinking island last year, President Donald Trump, who has referred to global warming as a “hoax,” called its mayor to assure him he has nothing to worry about.

In a view shared by many on the boat, State Sen. Jim Mathias expressed confidence that the island would be around for a long while. “It’s man’s hand intervening,” said Mathias, a Democrat who represents the lower Eastern Shore. “We have the top engineers working for us. We’ll figure it out.”

When the final phase of the jetty project is completed this fall — channel dredging and marsh restoration remain — it will mark the end of a chapter in the community’s history that started with, as some residents interpreted it, its proposed destruction.

In October 2012, Superstorm Sandy walloped the New Jersey coast and flooded lower Manhattan in New York City, and in Maryland caused extensive flooding in Crisfield and along the Bay shore in Somerset County. Smith Island suffered relatively little damage by comparison.

Still, state officials, conscious of the long-term threat to Smith posed by rising seas, set aside $2 million in federal relief money to buy out voluntary sellers. Plans called for homes or businesses acquired by the state to be torn down and future development to be banned on the properties.

“The people didn’t want to be bought out, and they were sort of insulted by it,” said Randy Laird, president of the Board of County Commissioners in Somerset County, which includes Smith island. “They felt like they (state officials) were trying to close down the island.”

The buyouts would have created a domino effect, Mathias said.

“Once it starts, it doesn’t stop,” he said. “It goes from one parcel to another parcel. And another family falls on hard times, and the state shows up with a check.”

Enter Smith Island United.

Forming Smith Island United

The archipelago has lost nearly half its population since 2000. Among the fewer than 200 who remain, one-third are age 65 or older. Most young people leave after finishing high school for lack of jobs on the island. “We didn’t really have a voice in government,” Somers said.

To push back against the buyouts, residents formed a civic group and began hosting regular community meetings. Those talks turned into Smith Island United. Somers, a part-time resident and captain of a state icebreaker boat, was installed as its president.

Soon, the organization persuaded the state to drop its buyout offer in favor of a “visioning” study. The report, finalized in 2016, outlined several possible actions for reversing the downward course, ranging from creating a seafood industry apprenticeship program to providing more public restrooms for island visitors.

That same year, Maryland named Smith Island a “sustainable community,” giving the community access to a suite of revitalization initiatives from the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development and grant programs. The island received a $25,000 grant last year to fix store facades because of the program.

In the meantime, long-stalled plans to shore up Smith Island’s marshy coastline began to materialize. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service built a $9 million “living shoreline” in the Glenn Martin National Wildlife Refuge, a marshy island that protects Smith’s north side from erosion. Then came a $4.5 million county project, completed in late 2017, that created another living shoreline on the island’s west side near Rhodes Point, its most endangered spot.

The Army Corps complemented that work with the construction of two jetties earlier this year, one on either side of an inlet called Sheep Pen Gut. Workers are expected to return in the fall to dredge the channel, deepening it from 3 feet to 6 feet. That will restore vessel passage through the island, eliminating the circuitous, gas-wasting journey that some watermen must take to reach the open Bay because the inlet has shoaled up.

Everett Landon caught a glimpse of the construction while standing on the second-floor balcony of a home still under construction.

“It looks very good,” said Landon, a Rhodes Point native who took over as pastor of the community’s three churches last year. “With the erosion we’ve been facing, people have been wondering how long until it makes them move away.”

The Rhodes Point jetty project had been on the books at the Army Corps since the mid-1990s. Some residents had all but given up hope that it would ever get built.

“You get a community that struggles a lot, and you get a project like this — it puts the wind in your sails. It just shows persistence,” Landon said.

Losing ground

He added that the help is especially welcome in Rhodes Point, where the 40 or so remaining residents live on an ever-shrinking strip of high ground. For his part, Landon measures that loss in the gradual disappearance of a beach once visible — high and dry — beyond the marsh that fringes Rhodes Point.

“My grandmother told me that when she was younger, she could sit on the second floor of her home and all she could see was sand,” he said. “When I was growing up, it was just a narrow strip and then marsh. When my kids came along, it was just gone.”

Most Smith Island residents have incomes tied to the seafood industry, from the crabs they catch or pick or the oysters they dredge. Support for Trump was near-unanimous on the island in 2016, and most share his skepticism toward human-caused climate change.

They concede that their island is vanishing, but they prefer to speak of it in terms of erosion instead of sea level rise.

Marianna Wehnes moved to Smith Island in 2011 to live with her boyfriend, and she quickly fell in love — with the island.

After her relationship with the man ended, Wehnes moved back to the mainland on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, only to return. She missed the community’s tranquil way of life and knowing her neighbors. She now works in one of Ewell’s gift shops, where eight customers walking through the door qualifies as a busy day.

The new jetties and restored marsh will help keep the island above water for a while, she agreed. Beyond that, Wehnes added, Smith Island’s fate will be up to a higher power.

“It’s been here 400 years, and it’s going to be here for 400 years,” she said. “The only reason it won’t be is if the good Lord tells it to go.”

So, $91,000-plus for each man, woman and child on the island to buy a few years more before it is swept away. Is that Larry Hogan’s brand of fiscal conservatism?