By Ryan D. Lang, M.D., MPH

For MarylandReporter.com

In my primary care practice, patients commonly ask for ways they can improve their diet to live healthier. But many of my patients live in areas where they lack easy access to the foods that I recommend.

Fresh fruits and vegetables are important in lowering the risk of heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and even some cancers. But according to researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, a quarter of Baltimore residents live in food deserts, which are neighborhoods with poor access to these healthy foods.

The percentage is even higher for the African Americans who make up the majority of the city.

Unfortunately, black residents also have higher rates of death due to heart disease, diabetes, and stroke compared to their white counterparts as measured by Baltimore City Health Department data. And those of all races who have a high school education or less have even higher rates of death from those causes.

All people, regardless of their education or race, should have equal access to fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods to help prevent deadly diseases.

Yet many grocery stores that sell these foods choose not to open in certain city neighborhoods. That’s a result of many factors, including business models that favor more affluent neighborhoods, as well as the long-term neglect suffered by many depressed areas of our city.

I strongly support local policies that will bring grocery stores to more of Baltimore’s food deserts. In the meantime, nutrition education can still make a world of difference in the health outcomes of our most disadvantaged city residents.

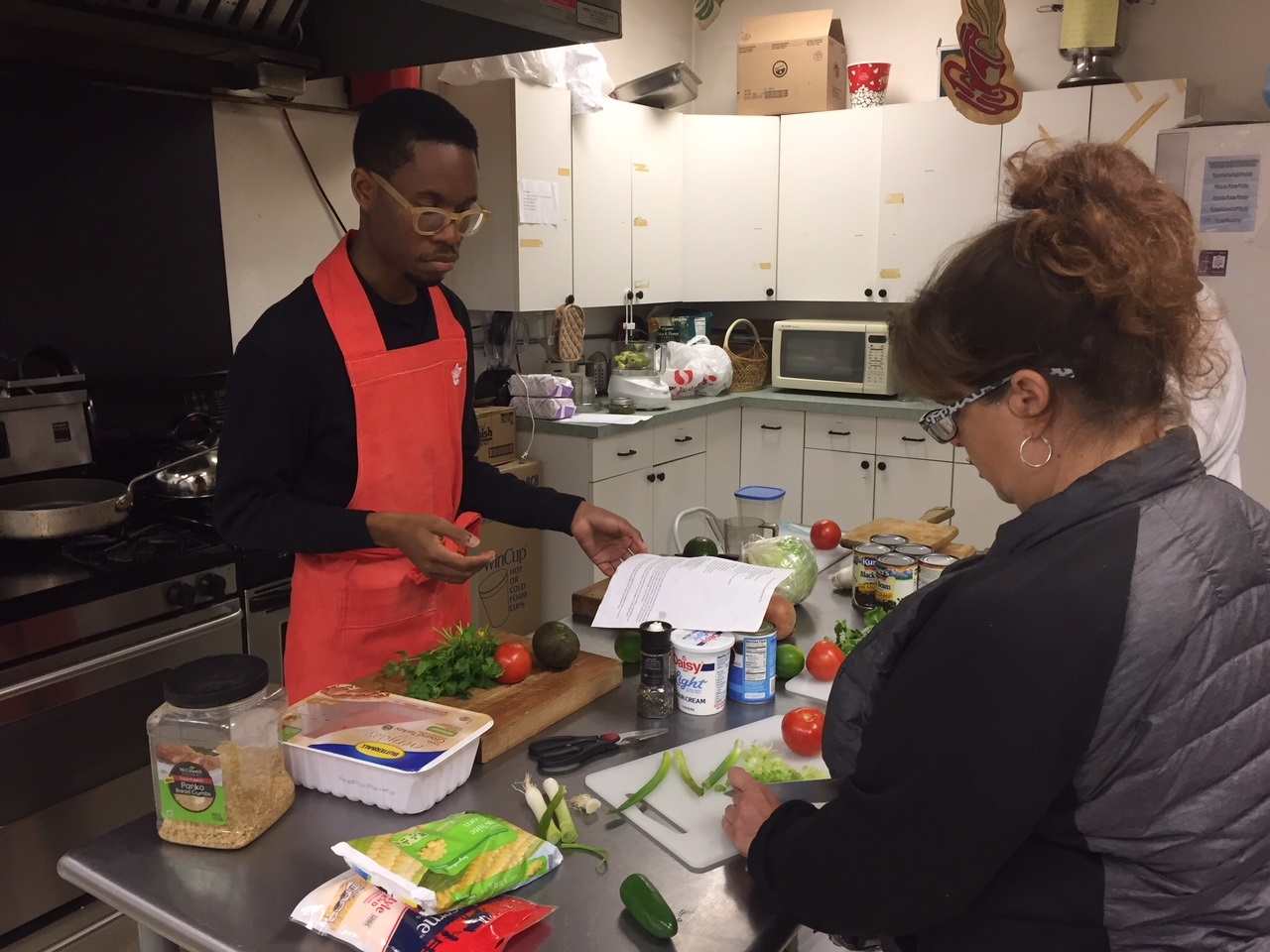

Cooking classes

About a year ago, I joined a cooking and nutrition education program organized by Johns Hopkins Community Physicians and the Church of the Guardian Angel in Remington. Dr. Tina Kumra, the medical director of the Remington Hopkins practice, and Rev. Alice Jellema, rector of the church, developed a program in which locals are offered free training in preparing inexpensive and nutritious meals.

As a preventive medicine doctor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, I led many of these weekly cooking classes. My colleagues and I chose easy, low-fat, and mostly plant-based recipes with large quantities of vegetables. Many of these meals only cost a few dollars per serving, and some don’t even require an oven or stove.

As community members cooked, I saw their confidence improve dramatically and witnessed some make better decisions outside of the kitchen, such as going easy with the salt shaker and choosing water to drink instead of juice or soda. Over the years, these small choices could translate to fewer people with high blood pressure and diabetes.

Nutrition education among low-income elementary school children and the elderly who participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) can lead to these individuals eating more fruits and vegetables, according to the USDA. This proves that nutrition education can have benefits even among low-income residents in Baltimore, many of whom live in food deserts.

Baltimore can hope for even greater progress soon. Recently, the health department got a $150,000 grant to teach local youth how to choose healthier foods from corner stores and how to prepare easy and nutritious meals at home. These skills can go a long way for young people, who may not get this training otherwise, and for those who don’t have access to full grocery stores near their homes or schools.

Hopefully, these skills can be passed along to parents, leading to an even greater public health impact. And ideally, corner store owners in Baltimore will make greater efforts to stock their shelves with fresh fruits and vegetables as well.

When kids learn how to make better choices with their food, they might make better choices in other ways as well, such as avoiding smoking and staying physically active.

Fixing food deserts won’t happen overnight. But nutrition education can be the first step toward leveling the playing field for disadvantaged people in Baltimore.

Ryan D. Lang, M.D., MPH is a New Economy Maryland Fellow with the Institute for Policy Studies and an internal medicine physician in Baltimore. He is also a general preventive medicine and public health resident physician at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Where is the personal responsibility of the people regarding buying nutritional food ?

The supermarkets have huge areas dedicated to vegetables and fruit… But, as I stood in line, I couldn’t help but notice that the carts of the people in front of me are loaded with junk food, snacks, and sugar drinks… And I know what EBT cards look like…

I could have that same card and buy better, more nutritional food and very few snacks…