By Blaine Taylor

For MarylandReporter.com

The best description of this spectacular new production is even-handed, balanced, and fair. If you’re watching it as I’ve been doing, you need no further appellations from me. If not, you should see the series when it’s repeated over the next several years. You won’t regret it.

Rather than tell you what you’ve seen or may see, therefore, I choose to inform you a bit of the magnificent new illustrated book based on the series. At over 600 pages and gleaned from a collective 24,000 color and black-and-white still images for both the film and the book, the author asserts that at least 20 more such volumes could’ve been published. Maybe someday they will be in an elongated, on-going series; I hope so.

Rather than tell you what you’ve seen or may see, therefore, I choose to inform you a bit of the magnificent new illustrated book based on the series. At over 600 pages and gleaned from a collective 24,000 color and black-and-white still images for both the film and the book, the author asserts that at least 20 more such volumes could’ve been published. Maybe someday they will be in an elongated, on-going series; I hope so.

Having perused all the thus far published general histories on Vietnam, my opinion is that this is the very best. Of special interest to American viewers of the first five “episodes” are the treatments of the pre-U.S. French colonial experience, the dual biographies of the two rival Vietnamese leaders—the South’s Catholic leader Ngo Dinh Diem and his Northern Communist rival Ho Chi Minh—plus the first four U.S. presidential regimes that grappled with the Southeast Asian dilemma: Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson.

Derived from these are over 100 terrific on-air and in print, first-person interviews with still living people from all sides of the spectrum. As a 1966-67 period veteran and historian, I found especially rewarding those from “the other side of the hill,” in Wellington’s famous phrase — the enemy.

How the Vietnamese defeated us

In the final military analysis, the Vietnamese defeated us the same way that they’d earlier beaten the French after a century of trying. This was mainly by refusing to engage in conventional, set-piece battles that the whites and colored colonial forces could win, but that the indigenous forces could not, despite their final 1954 siege victory that ended the First Indochinese War.

There was no such triumph over the Americans. Ironically, the 1965 Battle of Ia Drang was, however, just such a fight— won by us –in which the regular North Vietnamese Army was defeated, and of which it refused to ever fight again.

Could the North Vietnamese Army have someday bested the combined U.S. Army and Marine Corps in such a battle? I don’t think so.

Might an invading Communist Chinese force have done so in pitched battles against us? Again, I don’t think so, and—as it was—the Chinese did have 340,000 support troops engaged secretly in North Vietnam.

At the time, I both feared and expected that a more massive Red Chinese force might indeed sweep down from the north and give our commander, Gen. William C. Westmoreland, exactly that kind of battle he wanted, but it never happened. Then, I thought we might lose it.

One cardinal aspect covered neither in the book nor by the film—at least not yet, at any rate—is how the American Indochinese War was a throwback to the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39. In the latter, many of the tactics and weapons of the later, larger World War II saw their debut and testing. Fortunately, the Vietnam War never led to a third world war, but it could have.

As I write these words, indeed, America seems to be bracing for its second Korean war, alas.

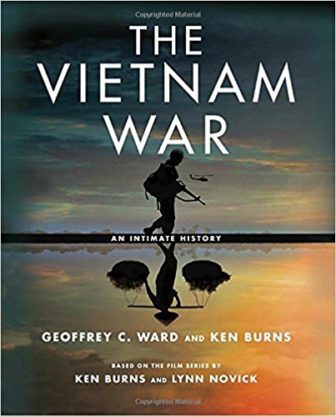

The Vietnam War: An Intimate History by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, Based on the Film series by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, New York: Alfred A. Knopf Publishing, $ 60, 2017.

Blaine Taylor was a combat military policeman in the U.S. Army 199th Light Infantry Brigade in South Vietnam, 1966-67. A long-time author of histories and biographies, Taylor covers one political aspect of the Vietnam War in his forthcoming 2018 biography “Bobby! From Robert F. Kennedy to RFK, 1925-68”.

A dissenting view from journalist John Pilger: “I watched the first episode in New York. It leaves you in no doubt of its intentions right from the start. The narrator says the war “was begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American overconfidence and Cold War misunderstandings. The dishonesty of this statement is not surprising. The cynical fabrication of ‘false flags’ that led to the invasion of Vietnam is a matter of record – the Gulf of Tonkin ‘incident’ in 1964, which Burns promotes as true, was just one. The lies litter a multitude of official documents, notably the Pentagon Papers, which the great whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg released in 1971.”

I noticed that at the beginning, and I was a little surprised. I had seen a bunch of advanced publicity of how it was going to present all sides, be balanced, etc. So I was surprised they gave their summary judgment right at the beginning. It would have been more appropriate if it had come at the end. Because I do think they labor to present a rounded view.