These comments were offered to the Maryland Redistricting Reform Commission

By Roy T. Meyers

Professor of Political Science, UMBC

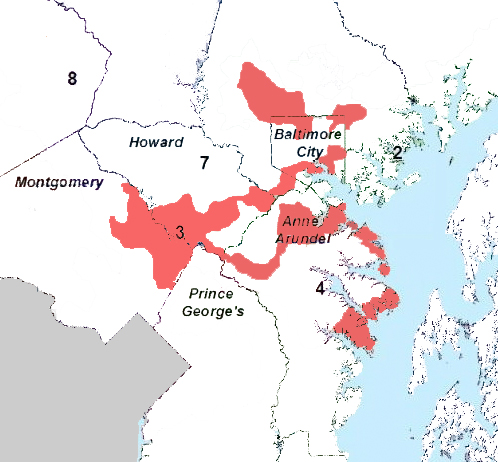

I hope that the commission’s work is the start of a serious examination of how to reform a process that is clearly flawed, as is most obviously shown by the shape of the congressional district in which I reside, the 3rd Congressional District.

I say this even though I lean Democratic and am glad that the partisan gerrymandering of Maryland partially offsets the extensive partisan gerrymandering conducted by Republicans in many other states.

On the other hand, designing districts to maximize partisan advantage, or alternatively to maximize incumbent protection, is not the way citizens should want legislative districts to be drawn. Voters should be able to choose their representatives, and not the other way around.

Balancing attributes

In general, therefore, I would prefer that a balanced commission draw legislative districts–if, and this is a very important if, the commission would be expected to sensibly balance the multiple attributes of a desirable districting plan.

Maryland has a wonderful tradition of using commissions and task forces, whether created by the legislature or governor, to investigate complicated issues by engaging the public and by drawing on policy experts.

I believe experience also shows that the most successful groups of this type are those that take the time that is necessary to fully discuss controversial issues, hearing from all sides, so that there is more of an opportunity to reach a meeting of the minds.

Regarding the substance, I haven’t done original research on this issue since graduate school; my research specialty is instead government budgets. I have long followed and commented on Maryland’s budget, without regard to my partisan preferences, based on the belief that it is in the benefit of all Marylanders that the state’s budget be prudent and that it efficiently allocate resources towards our highest priorities.

Difficult trade-offs necessary

As you know, budgets almost always require decision-makers to make difficult tradeoffs. This is also the case for designing legislative districts, whether it is done by partisan politicians or appointed commissioners.

I already provided a recent article by Josh Ryan and Jeffrey Lyons, which finds that the districts drawn by commissions are similar to districts drawn by state legislatures, in both the partisan balance of voters and the voting behavior of representatives.

This suggests that if you want a Maryland commission to produce a better outcome, it will need to be carefully structured. It is therefore very important that you not accept simplistic recommendations for how a commission should be charged with its important task.

Instead, you should provide suggestions on how a commission could balance the sometimes conflicting guidance provided by different standards for redistricting. There is one standard for redistricting that must be met–population equality across districts, as defined by the Supreme Court. But many other posited standards for redistricting are harder to interpret and put into practice.

Contiguity

Let’s start with contiguity, a standard that appears to be violated by the shape of the 3rd district, unless you are traveling by boat between Gibson Island and Annapolis. Note, however, that these two locations could be viewed as members of a “community of interest.” To many on the shore, the state of the Bay is a very important concern, and traveling by boat to visit those who share that interest is a common behavior.

Arguably, then, contiguity should not be restricted to areas connected by land. Using a community interest standard, it would be easy to justify a district that combined the southern Eastern Shore with Southern Maryland–which was the case, for example, during the 1970s and 1980s.

Compactness

Regarding another geographical standard, compactness, the aforementioned 3rd district is obviously not compact. But what changes would be necessary for it to be sufficiently compact?

Going beyond that, would it be possible to take politics out of redistricting by requiring that districts, above all other considerations besides equal population, maximize compactness?

In the debates about Maryland’s maps, some have implicitly supported this view by stating that the “best” shape for districts is a square, or alternatively, a circle. Math and mapping experts have proposed various algorithms that they claim would produce compact and unbiased districts. However, their different algorithms can produce quite different results.

Note also that Maryland has a non-compact shape in the first place. But the most important problem with over-relying on the compactness criterion is that it doesn’t match the principle that legislators should represent people, not geographical shapes on the map.

Population not distributed evenly

This is important because it is almost always the case that the population is not distributed evenly across the map.

For example, a clear finding from political science research is that, across the country, Democrats are more concentrated geographically than are Republicans. While this is a bit less the case in Maryland, it is likely that using a strict compactness standard in Maryland would cause Democrats to “waste” proportionately more votes, similar to a “packing” strategy that would be employed by Republicans if they were able to design a partisan gerrymander.

In other words, using a strict standard of compactness in hopes of taking politics out of the process would have the opposite effect.

Note that in making these observations, I am not opposing the value of compactness. Getting back to the 3rd district, its design makes it difficult for the incumbent to have a personal presence in the many communities that it covers. District designs should not encourage legislators to communicate mostly through robocalls and mailers.

So it would be useful to list compactness as one of several important criteria that a commission should weigh in judging alternative designs; it just shouldn’t be the dominant one.

Observing city and county lines

Another standard that is often suggested is that districts should minimize the crossing of county/city lines and the breaking up of counties into multiple districts. This is a particularly difficult standard to use when you must have eight Congressional districts with equal populations, given the varying sizes of Maryland’s 24 county-level local governments.

While it is desirable not to split counties unnecessarily into numerous Congressional districts, a redistricting commission should have the flexibility to cross county lines.

“Communities of interest,” which can be defined in many different ways, often cross local government lines. It could also be valuable to have heterogeneous districts that combine areas represented by different local governments.

For example, a district that includes part of Baltimore City as well as parts of the surrounding suburban counties might produce a representative who sees the value of policy that encourages more cooperation and burden sharing between these local governments.

Making districts more competitive

At the national level, some advocates have suggested that a major goal of redistricting reform should be to encourage many more diverse districts, in order to offset how Americans have increasingly sorted themselves geographically into communities that are quite homogenous in economic class and ideology.

If redistricting combined these different neighborhoods so that Congressional districts became more diverse, those districts might also be more competitive electorally, leading to less extremism in the Congress. However, the bulk of evidence so far shows that representatives from districts with more moderate electorates behave little differently from their colleagues who represent very liberal or very conservative electorates, though this may not be the case in the future.

There’s another potential problem with designing more districts to be highly competitive–they may not stay that way.

If a national election favors one party very strongly, one party can win many seats in a landslide. That party can then protect those gains by using the advantages of incumbency to put an effective lock on those seats until the next redistricting.

This leads to the questions of whether there should be a standard that rules out partisan bias, and if so, how that bias can be measured. Regarding the latter, it is sometimes suggested that the percentages of seats held by each party should be the same as their percentages of votes for congressional candidates.

But this correspondence is highly unlikely in a single-member district election system as the parties’ vote shares move away from a 50-50 split. Single member districts almost always produce a bonus to the party with the larger vote share.

Political scientists call this relationship the “seats-to-votes curve”–but the shape of that curve is affected by numerous factors besides districts designed to produce partisan bias.

A better method for measuring partisan bias has been developed by political scientist Gary King and his colleagues, which is the symmetry standard. It “requires that the electoral system treat similarly-situated political parties equally, so that each receives the same fraction of legislative seats for a particular vote percentage as the other party would receive if it had received the same percentage.”

Statistical analysis of previous election results are used to estimate whether proposed redistricting plans violate this standard.

The final standard that you must consider is how Maryland can comply with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. This is such an important and complicated issue that I believe your group must reach out to more experts to evaluate how a commission might address this issue in comparison to how Maryland’s elected officials have treated it.

Not simple

In general, then, it is not a simple matter to determine whether a districting design is fair. The greatest potential of the commission approach is that it might reduce partisan and incumbent protection motivations in designing districts, but there will likely still be criticisms of any plans that a commission proposes.

I don’t have complete suggestions for how a commission should be constituted and how it should operate, but I do believe the following characteristics are most desirable.

It should have a relatively large membership–a dozen or more, with a mix of partisans and non-partisans, and be racially and geographically diverse. A large supermajority should be required for a plan. The commission should, as is current practice, draw on staff expertise in the Department of Planning and the General Assembly. It should encourage the public to suggest alternative plans, and provide a long public comment period on several alternative draft plans.

Reaching out to other governors

I will conclude with a comment on the politics of this issue. As many observers have noted, Maryland Democrats will not unilaterally disarm when the balance of redistricting power across the states is in the hands of Republicans.

This means that you, and the governor, should think about how to entice the Democrats to support your proposal. I sympathize with Maryland Republicans about this, for they are understandably aggrieved about how previous plans have treated them.

But I hope you and the Governor will move on, with the goal of proposing a bill that can pass, not one that will be a partisan blame-generation issue for the 2018 campaign. There are three things you can do towards this end.

First, as I’ve already suggested, you should explicitly reject a strict compactness test that would be biased against Democrats. Second, you should consider endorsing a national mandate for commissions in all states, such as the approach proposed by California Representative Alan Lowenthal.

Unfortunately, given the behavior of this Congress, it seems unlikely that his bill will get a fair hearing. So the third suggestion is that you call for a bilateral treaty with another state, a point that Delegate Reznik also made in the open letter he sent to you.

For example, Maryland’s implementation of commission redistricting could be made contingent on similar passage in a state with a Democratic Governor and a Republican legislature where the district map is biased towards Republicans. Drive north from here and you’ll soon enter a state with these characteristics–Pennsylvania. You should ask Governor Hogan to call Governor Wolf, and start a negotiation over cutting a bipartisan deal.

Roy Meyers is Professor of Political Science and Affiliate Professor of Public Policy at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, and a fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration, [email protected]

Recent Comments