By Leslie Middleton

Bay Journal

The federal government is one of the Chesapeake Bay watershed’s largest landowners and manages an area roughly the size of Delaware’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, or 5.4 percent of the entire basin.

The land and facilities it controls share little in common except that they are all under federal management, and their owners, like all landowners, have a responsibility to reduce their pollution to meet the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load.

Whether the feds are meeting that obligation, and exactly what it is they are doing, has not been an easy question to answer. But the answer is important for symbolic and very practical reasons.

Symbolic and practical reasons

On the symbolic side, as Rich Batiuk, associate director for science of the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program office, said, if federal agencies are seen as lagging, “this can pose a big impediment when talking to a farmer in Pennsylvania or a small municipality in New York that might be thinking, ‘Well, if the feds aren’t doing it, why should we?’?”

On the practical side, state and local governments are working to achieve nutrient reduction goals set in the TMDL. Whether they can meet those goals — especially for those with substantial federal holdings — can depend on whether federal managers are doing their part. Toward that end, the Bay Program, together with local, state and federal managers, are trying to better document what is happening on the watershed’s far-flung and diverse federal lands and facilities, as well as ensure that they are taking actions that will help meet Bay goals.

The task challenges everything from the bureaucratic makeup of governments to the mathematical brains of computer models.

Federal properties not alike

Complicating the effort: No two federal properties are alike. The U.S. Forest Service manages the watershed’s largest component of federal lands, 1.4 million acres, but the Department of Defense, with 440,000 acres, has the highest percentage of developed lands. This difference in land use makes developing and coordinating consistent policy “a pretty big hill to climb,” Batiuk said.

Federal land holdings are also scattered across six states and the District of Columbia, and the states’ pollution reduction plans vary widely. While all federal facilities have an impact, in some places it’s bigger than others. For example, at least 33% of the land in DC is owned or managed by federal agencies. In Virginia, that number is 12%.

“Many of these facilities are right on the Bay or on major tributaries because of their missions,” said Jim Edward, deputy director of the Bay Program office. Because they deliver pollution loads directly into waterways, these facilities are often key to the jurisdiction’s strategies for meeting its pollution reduction goals.

Federal agencies that own the facilities aren’t anything like the states, which have a common structure for accountability, management and reporting. If they were, life would be more simple for the federal managers in charge of controlling pollution to achieve the Chesapeake Bay TMDL.

And, it would be easier for Bay Program managers to assess just how well federal facilities and agencies are doing.

Obama’s executive order

President Obama’s 2009 Chesapeake Bay Executive Order directed federal agencies to lead by example in the effort to restore the Chesapeake. It brought multiple federal agencies formally into the Bay restoration program by creating the Federal Leadership Committee, a group chaired by the EPA made up of representatives from the EPA and the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Homeland Security, Interior and Transportation.

Federal agencies are supposed to work with the states to support their watershed implementation plans, or WIPs, the local plans to achieve the Chesapeake Bay TMDL. The WIPs include how each state will estimate nutrient and sediment loads from federal lands and facilities, and identify load reductions.

The EPA’s first evaluation of federal agencies’ progress to include their buildings, installations, structures, land and property in state plans came in 2013. It found that data provided from the federal facilities to the jurisdictions were uneven from state to state and in most cases incomplete.

The EPA cited lack of land use data; incomplete inventories of best management practices at federal facilities; and issues with incomplete reporting or reporting in a format that could not be used.

June EPA report

The EPA’s most recent evaluation of federal progress toward the TMDL was released in June and cited successes and areas of improvement, but noted that there has been uneven progress across agencies, and called for “more interaction and coordination related to planning, implementing and reporting best management practices on federal land in particular.”

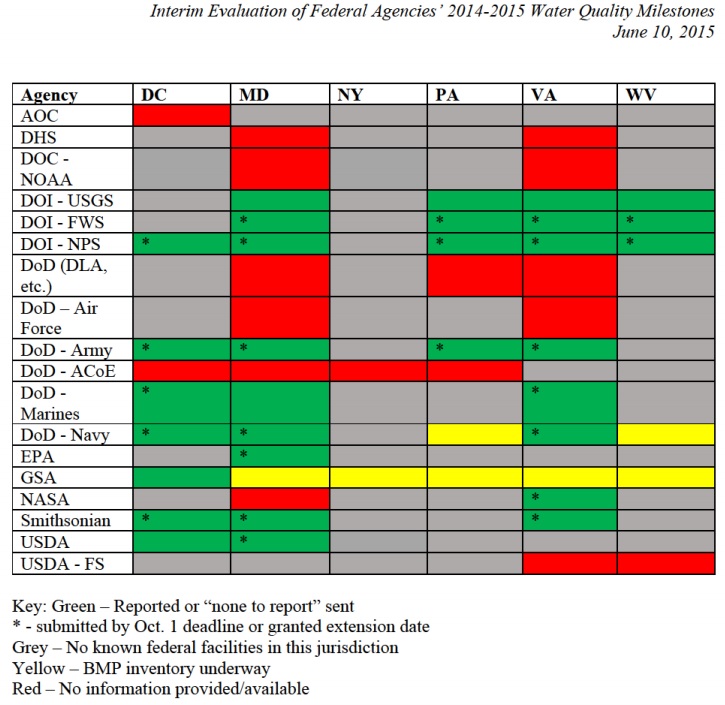

The evaluation included a color-coded chart that characterized the status of data submission by each federal agency to each of the six Bay states and the District of Columbia: green for “BMP data reported,” yellow for “BMP inventory under way,” and red for “no information provided or available.” The chart’s patchwork of colors highlights the need for many of the federal agencies to improve their reporting.

“The evaluation chart was intended to spur more communication between the federal agencies and the states,” said Greg Allen, who has guided the Bay Program’s Federal Facilities Team for six years. Since the evaluation was released, he said, agencies whose data reporting was incomplete have already reached out to the Bay Program to see how they can do better.

Allen also noted that a lack of reporting doesn’t mean that agencies are not good environmental stewards. Federal agencies are required to comply with federal and state regulations, and lack of data didn’t necessarily mean lack of progress.

For example, the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act requires federal construction projects that exceed 5,000 square feet to maintain or restore pre-development hydrology.

By the time the states were required by the Bay TMDL to provide data that accounted for land use, as well as their planned urban and agricultural best management practices, they had already been through many years of developing input for the Bay Program to be used in the tributary strategies, the precursor to the Bay TMDL.

Federal agencies “are fairly new to [the kind of reporting] at the level we set expectations through the executive order and the TMDL,” Allen said.

Cooperation with local governments

To bridge the information gap between what the states need to measure progress and what the federal facilities were providing, the Bay Program created the Federal Facilities Targets Action Team to bring together representatives from local governments and many of the federal agencies that own land in the Bay watershed.

Their work produced protocols that will make it easier for federal agencies to submit data needed by the states to report toward meeting cleanup goals. It will also allow the Bay Program to more accurately assess individual federal facilities’ progress toward restoration goals.

In addition, the team, originally formed with only federal agency representatives, now includes state representatives.

“This has been a really great development out of our work with the action team,” Allen said. “When the federal agencies and jurisdictions are talking, everything just works better.”

Overall, many of the federal agencies are doing more than they are getting credit for, Allen said. “They’re doing a lot of excellent work, and when the communication improves, we’ll be able to see the extent of this work.”

The Department of Defense created its own modeling tools to help assess options for pollutant reductions at its facilities because the Bay model and its scenario tools were unable to provide this analysis on a parcel-by-parcel scale.

That resulted in a new tool called BayFAST that can run different scenarios for each federal land holding to help them determine the best way to reduce pollution.

Allen said the Defense Department’s initiative to develop its own tool “could certainly be the ‘leadership by example,’?” that President Obama has requested of agencies.

No budgets for stormwater

In addition to providing better data to the states and local governments, federal agencies also need to do the work.

But the Defense Department and most of the other federal agencies often do not have the budgets to upgrade stormwater facilities — and can only seek additional funds if there is a regulatory requirement. This makes it difficult for a facility that is not covered by a stormwater permit or a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit to seek funding for additional stormwater management.

Even if they did have the budget, it’s not an easy time for any of the agencies. While the Bay Program has gotten adequate funding from Congress, “the other agencies are faring worse in terms of funding,” said Nick DiPasquale, director of the EPA Bay Program offices.

“Many of them do not have the level of resources they need to do what needs to be done — and it’s always difficult when your primary mission is other than what is stated in the Executive Order.”

Bay is not part of core missions

Sarah Diebel, the Department of Defense Bay Program coordinator, said, “We have to compete for funding with other projects required to support mission readiness.” And the price tag for federal projects may be larger for the feds than what a local government or private entity would pay, Diebel said, because the armed services are required to consider the costs of maintenance into perpetuity.

Though several federal agencies, like National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Geological Survey and National Park Service, set up house years ago near the Chesapeake Bay Program’s Annapolis offices, the executive order brought in new players, like Homeland Security, the Department of Transportation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

DiPasquale says that the challenges the Bay Program has had with federal facilities have mostly been growing pains. “As we reach out to more diverse partners, there are always going to be these kinds of issues that we have to work through.”

“It’s not working as quickly as I would hope —nothing ever does — but it is moving in the right direction. We’ve made progress in establishing a greater level of responsiveness.”

“When we discuss the Chesapeake Bay Program issues, we have to remember that, unlike for us, cleaning up the Bay isn’t the first things on their minds in the morning,” DiPasquale said.

Recent Comments