By Len Lazarick

Len@MarylandReporter.com

I feel compelled to add my own little stream of memory to the flood of recollections surrounding the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination Friday.

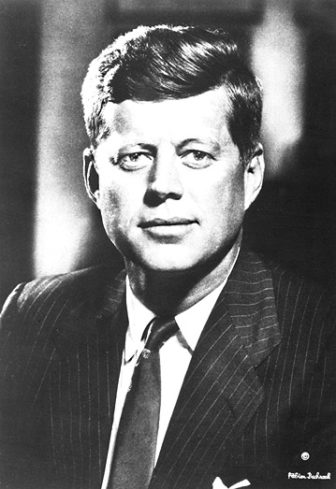

Surely many under 55 must marvel at the way their elders hold onto this event and this flawed man. For me, not only was the assassination part of my adolescent formation, but it had a real influence on my involvement in political life. Combined with the writing that I also did as a youth — I won a newspaper writing contest at age 10 or 11 — I can look back and see the beginnings of the meandering line that brought my career to where I am today.

I can remember watching some of the 1956 Democratic convention on black and white TV — or maybe I am remembering the rebroadcasts in later years of that convention when John Kennedy was a serious candidate for vice president.

Seeing JFK in person

Certainly I watched the 1960 Los Angeles convention in which he was nominated. I especially remember that chilly day in October 1960 in the run up to the election that we waited hour upon hour for Kennedy to arrive at the Levittown, Pa. shopping center for a rally.

He had been in a motorcade that was supposed to pass a half block from our house in Croydon, but my father drove me, then a 6th grader, up to Levittown for the speech. Little did we know that the motorcade from Philadelphia up Route 13 was to take hours as it passed slowly along the crowded route through the mostly white and very Catholic section of northeast Philadelphia and its suburbs.

When candidate Kennedy finally arrived, I have no recollection of what he said, nor does my 90-year-old father. But I do remember how tan he was. He was such a handsome figure.

After his election, I kept a signed photo of Kennedy in my bedroom.

For ethnic Catholics, this wealthy Harvard-educated war hero was a confirmation of possibility, breaking the faith barrier. He won the hearts of many others as he conducted himself with wit, charm and eloquence in weekly televised press conferences, an innovation no other president has followed.

In the minds of my generation, he is a far greater president than his sparse record would indicate. But we believed he had the potential to be a great chief executive, and that possibility was frozen in time on Nov. 22, 1963.

The illnesses and infidelities

Only later did we find out what a desperate womanizer he was, and how many medications he took to relieve the constant back pain, the Addison’s disease, and the colitis that he suffered for decades. All this and his frequent hospitalizations had been covered up for years.

According to my favorite Kennedy biography, “An Unfinished Life” by Robert Dallek, Kennedy and his brother Bobby feared his infidelities and illnesses would somehow come out before his reelection bid or during his second term. There were rumblings of his sexual escapades in fringe publications, but they had not made it into the mainstream press. The Kennedys knew that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had files on the affairs, and the connections of some of the women to mobsters and foreign powers.

If this salacious material had come out, it could have destroyed a presidency depicted as an idyllic family with a beautiful wife and cute children headed by a strong and robust leader, not a sickly philanderer. In spite of these debilities, it is remarkable how well he performed the job.

Johnson fulfilled the Kennedy promise — at first

At his death, Kennedy was all possibility, and it was Lyndon Johnson, master of the Senate, who actually engineered congressional passage of his legislative initiatives — civil rights, Medicare, the anti-poverty programs and even the tax cuts that Kennedy hadn’t been able to pass.

Many historians believe Kennedy would not have sent increasing number of combat troops to Vietnam as Johnson eventually did to his great undoing. I did not know that during the 1964 campaign when I would take the bus down 17th Street from St. Joe’s Prep to volunteer in the Johnson-Humphrey-Blatt headquarters in downtown Philadelphia. GOP nominee Barry Goldwater was the war monger, not Johnson, who was fulfilling the Kennedy legacy. How wrong we were.

Johnson was the first politician to sorely disappoint me, but certainly not the last. He was the last politician whose election I ever worked for.

First national tragedy on live TV

The Kennedy assassination and funeral was the 9/11 event for the leading edge of the boomers, the first national tragedy experienced by over a hundred million people on live TV. However, the focus in 1963 was not the terrible death of thousands on 9/11, but one leader loved and admired by millions.

Before and after his death, a whole coterie of retainers burnished his memory and covered up his flaws. I know what we hold onto is more myth than reality. Like any funeral, we mourn not just for the dead, but for our loss. We need our civic myths, and Kennedy was one.

The films and pictures from that presidency and that awful weekend of mourning can still make me cry, and it was the first time I can recall sharing a cry with my father as we watched it on TV.

Kennedy’s death meant his wit and charm, his eloquence and elegance, and above all his potential and his promise were frozen in time. Had he not been killed, we senior boomers and older would perhaps not remember him so fondly. But we do.

I was only 5 when I saw JFK the same day as he went by where Holy Family University is now. My parents took me, my younger brother and sisters. My reaction too was “Wow he has a tan. It’s October!” I can still see him sitting up on the top of the back seat waving.

Sad. After getting burned by military advisors leading to the Bay of Pigs fiasco, it was unlikely he’d amp up U.S. military involvement in Viet Nam.