By Len Lazarick

Len@MarylandReporter.com

You may soon find General Assembly committee votes online and maybe even watch or listen to Webcasts of these crucial voting sessions, which decide life or death for every bill.

The push for relatively inexpensive good government measures is especially attractive this year when there is no money to spend on new programs.

But the move to greater openness and accountability in Annapolis is not without its partisan bumps.

Senate President Mike Miller and House Speaker Michael Busch seem to be on-board. Miller continues to insist the Senate is already doing much of what’s being requested. Miller and Busch both know that they can achieve more online openness on their own, even without the rule changes Republicans have proposed.

The Senate started posting committee votes electronically last year in the journal that comes out long after the session is over. Few people knew the PDFs of hand-recorded tallies were there, including most reporters.

Anyone can also call the information desk in legislative services several days after a committee vote to get a rundown (8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., 410-946-5400).

The House journal does not include committee votes, but The Gazette reported last week that the chamber is moving committee vote results online and some proceedings to streaming web video.

Republicans have riled Miller by proposing a rule formally stating that committee voting sessions are open. The sessions already are open to the public, but Sen. Nancy Jacobs, the minority whip, wants to make that clear in Senate rules – which, by the way, have never been posted online.

Jacobs told me and apparently others that she had heard the Education, Health and Environmental Affairs Committee had closed some voting sessions. This led to an unusual and highly oblique rebuke from a member of her own party on the Senate floor Friday.

Sen. Richard Colburn, the flexibly-conservative Republican from the Middle Shore (Cambridge), rose on a “point of personal privilege.” This allows a senator to respond to an attack, often in the news media.

On this occasion, Colburn rose as the ranking Republican on the committee in question. He defended not himself, but his chair, Joan Carter Conway, a feisty liberal Democrat from Baltimore City.

“On the Eastern Shore we say, ‘I heard’ and ‘he said’ are the two biggest liars in the world,” Colburn said.

“I’d like to make it perfectly clear, despite what you may have heard, … all the bill hearings and all the voting sessions in the Education Health and Environmental Affairs Committee have been open to the public,” Colburn said. “We have had no closed hearings, we have had no closed voting sessions.”

Most of those listening were probably puzzled about what Colburn was talking about. Presiding officer Miller thought the response had something to do with politics surrounding one of Colburn’s top legislative priorities.

“I guess that means that [Colburn’s] oyster dredging bill is going to come to the floor,” referring to a bill in the committee. “What do you think folks?” Miller asked the Senate, chuckling at his own quip for almost 12 seconds. Then he got serious.

“It’s very important that we make certain all our proceedings are open pursuant to the law, and we thank you [Colburn] for that observation,” Miller said.

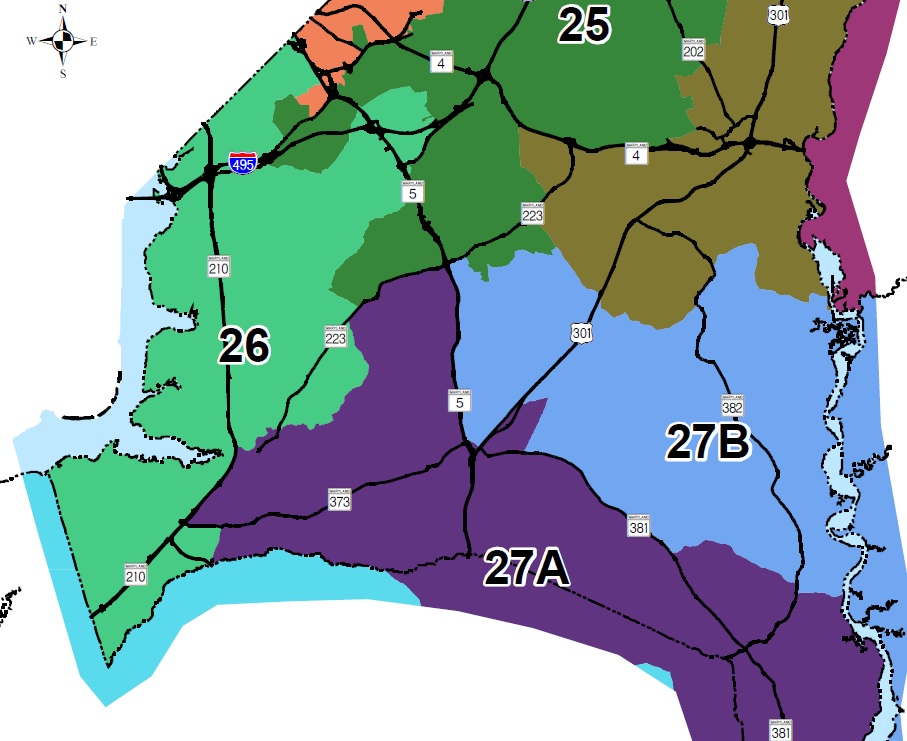

Carter Conway and her vice-chair, conservative Democrat Roy Dyson from St. Mary’s, both denied that any voting session had been closed under their leadership. Committee member Jim Rosapepe, a College Park Democrat, couldn’t remember any either.

Having voting sessions broadcast on the web in audio or video would be a huge improvement.

Voting sessions, called “markup” on Capitol Hill, contain the fullest and frankest discussion most bills ever get. Hardly anybody but senators, delegates and committee staff are in the room.

Lobbyists are actively discouraged from attending voting sessions, Conway conceded, a practice followed by committees in both houses.

Reporters seldom attend voting sessions. For one, the voting is often late in the afternoon, after hearings, when many reporters are wrapping up stories for the day. Two, reporters often don’t know when the votes will occur and what is being voted on. Three, even if a reporter attends, it’s hard to figure out what’s going on. The voting list is often only comprised of bill numbers and only the lawmakers and staff get copies of the list and any proposed amendments.

Sometimes in past sessions, on a late Friday afternoon, I would wander over to to a voting session of the House Judiciary Committee, a panel handling some of the most interesting and controversial bills in the Assembly. The few times I attended, I would be the only person in the public side of the room. I would ask Del. Todd Schuler, a Baltimore County Democrat and the closest delegate to the press desk, to see his voting list.

Nobody tried to throw me out. But then again I didn’t see the voting list before the meeting. The bills to be considered were determined earlier by a private confab of subcommittee chairs in a backroom. These private meetings before the meetings go on in every committee.

The current proposals for putting committee votes, hearings and voting sessions online are a big step forward in opening the work of the Assembly. But there are still too many decisions made behind closed doors.

The public’s business needs to be conducted in public.

Recent Comments